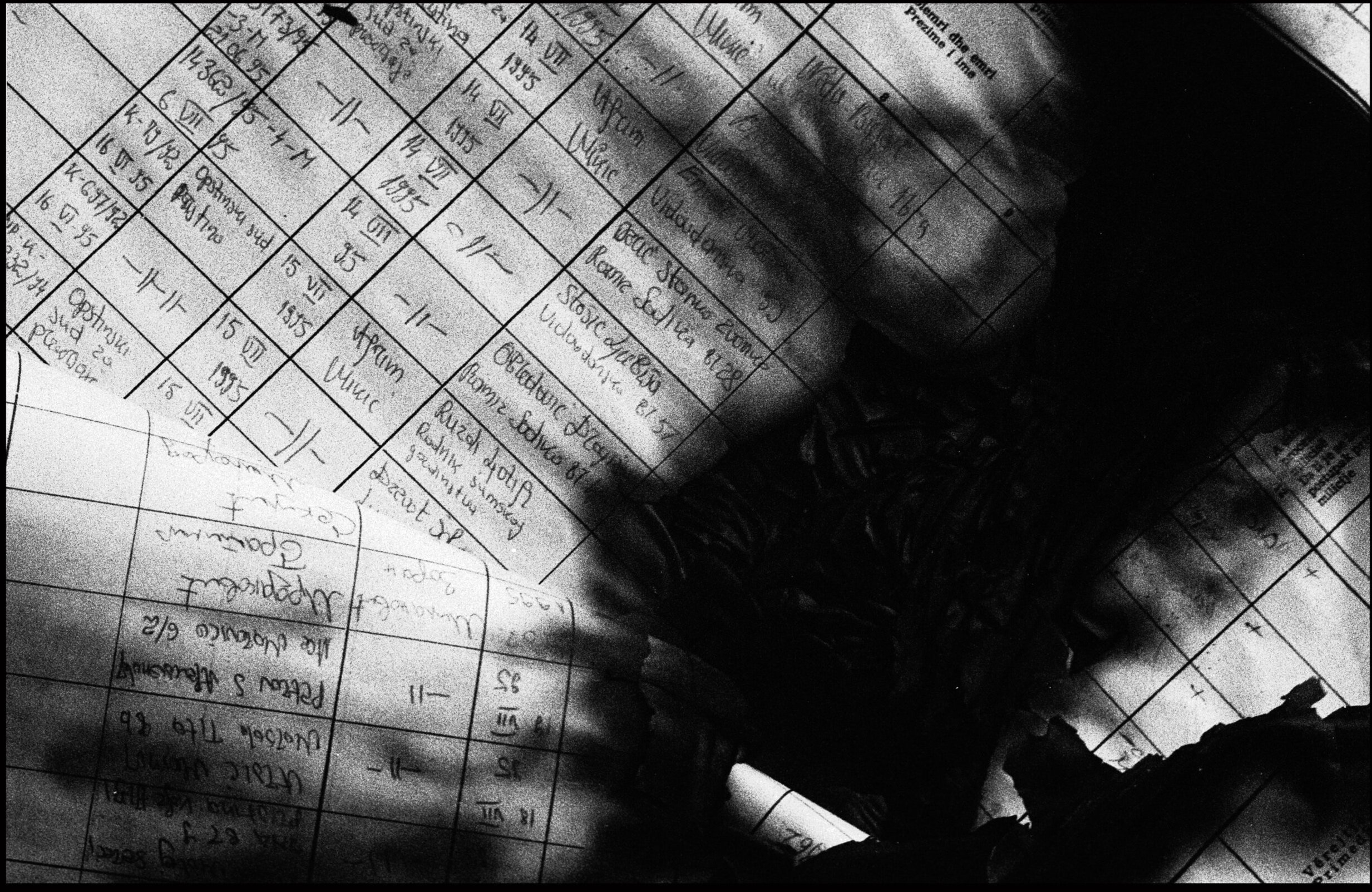

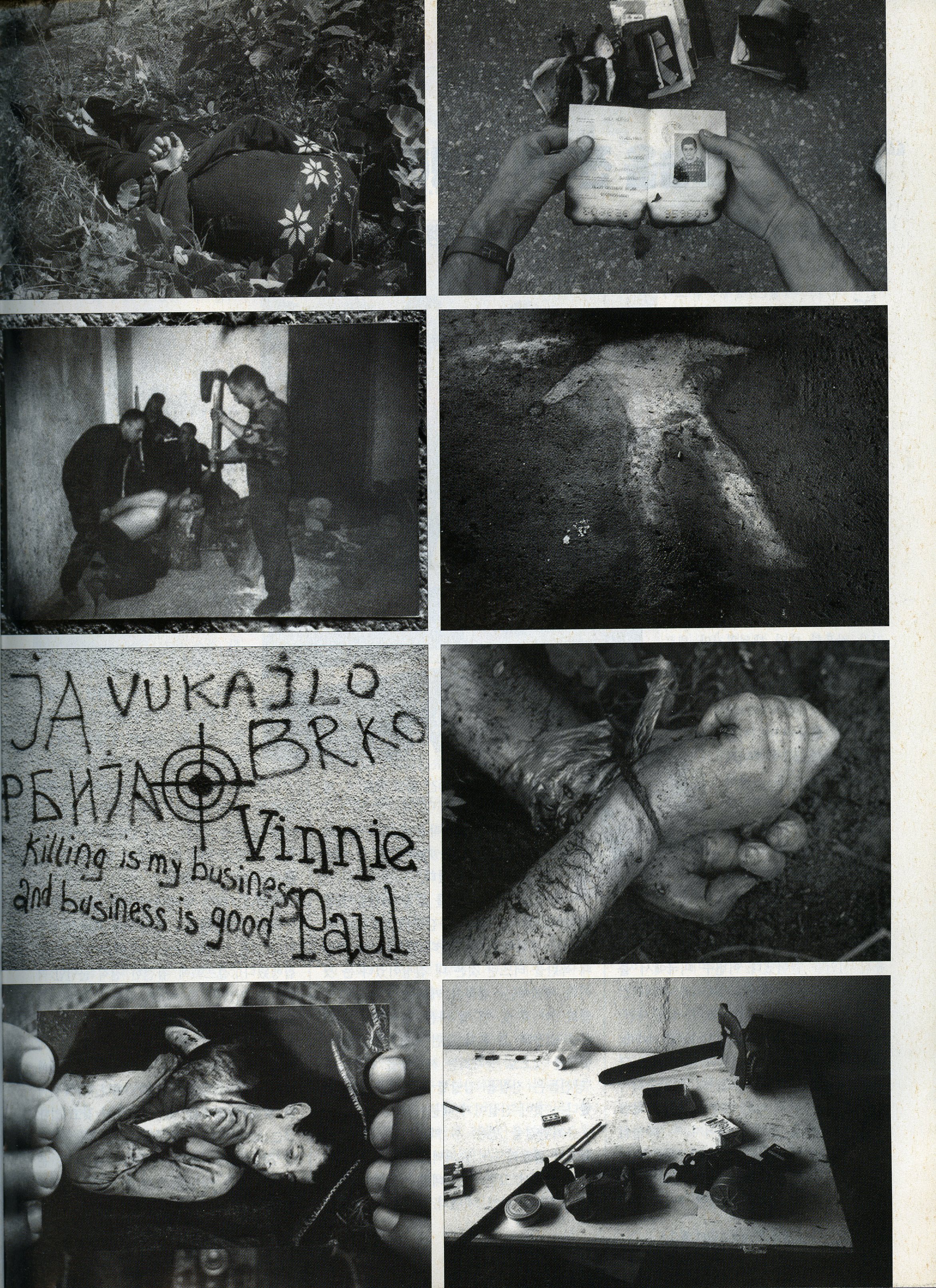

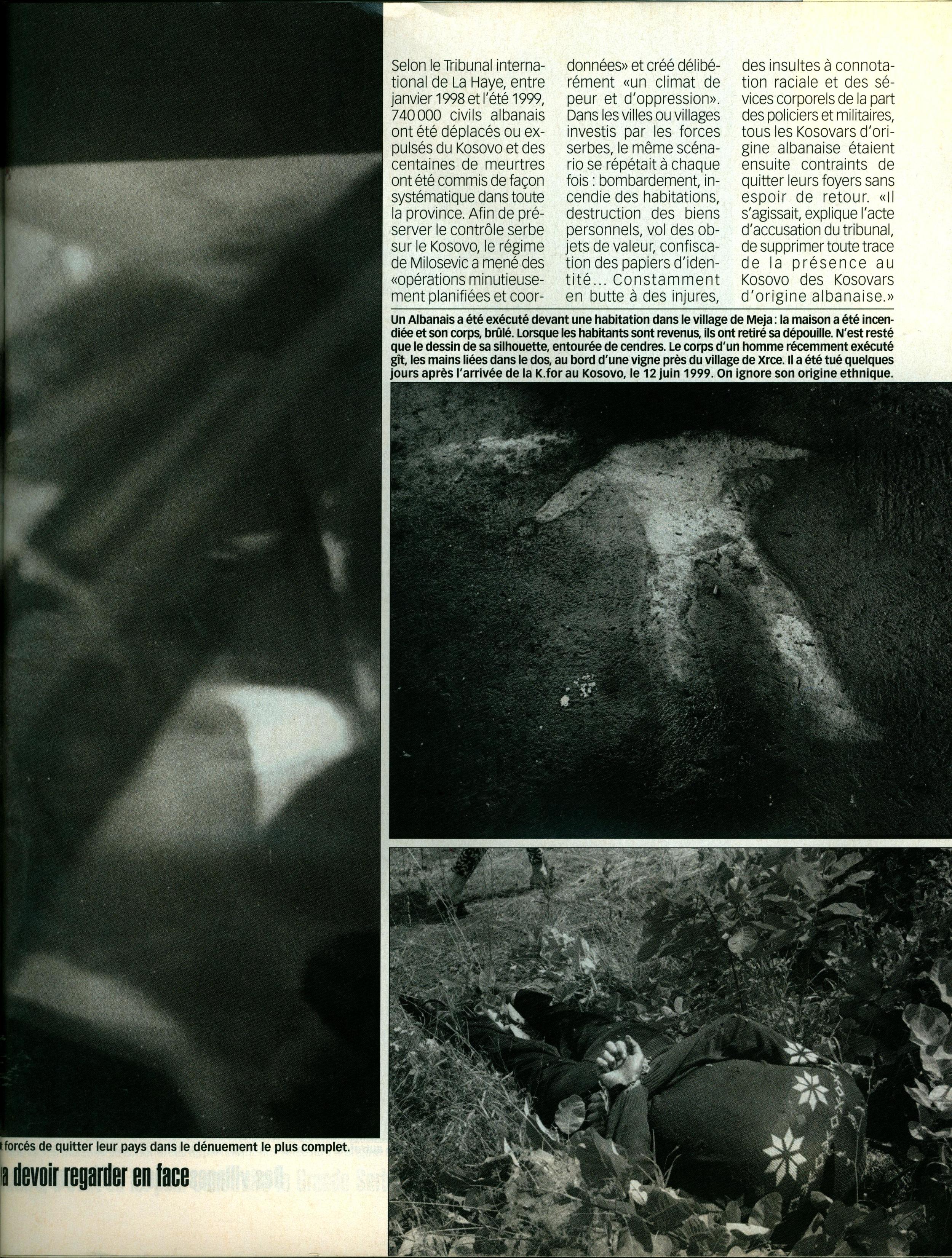

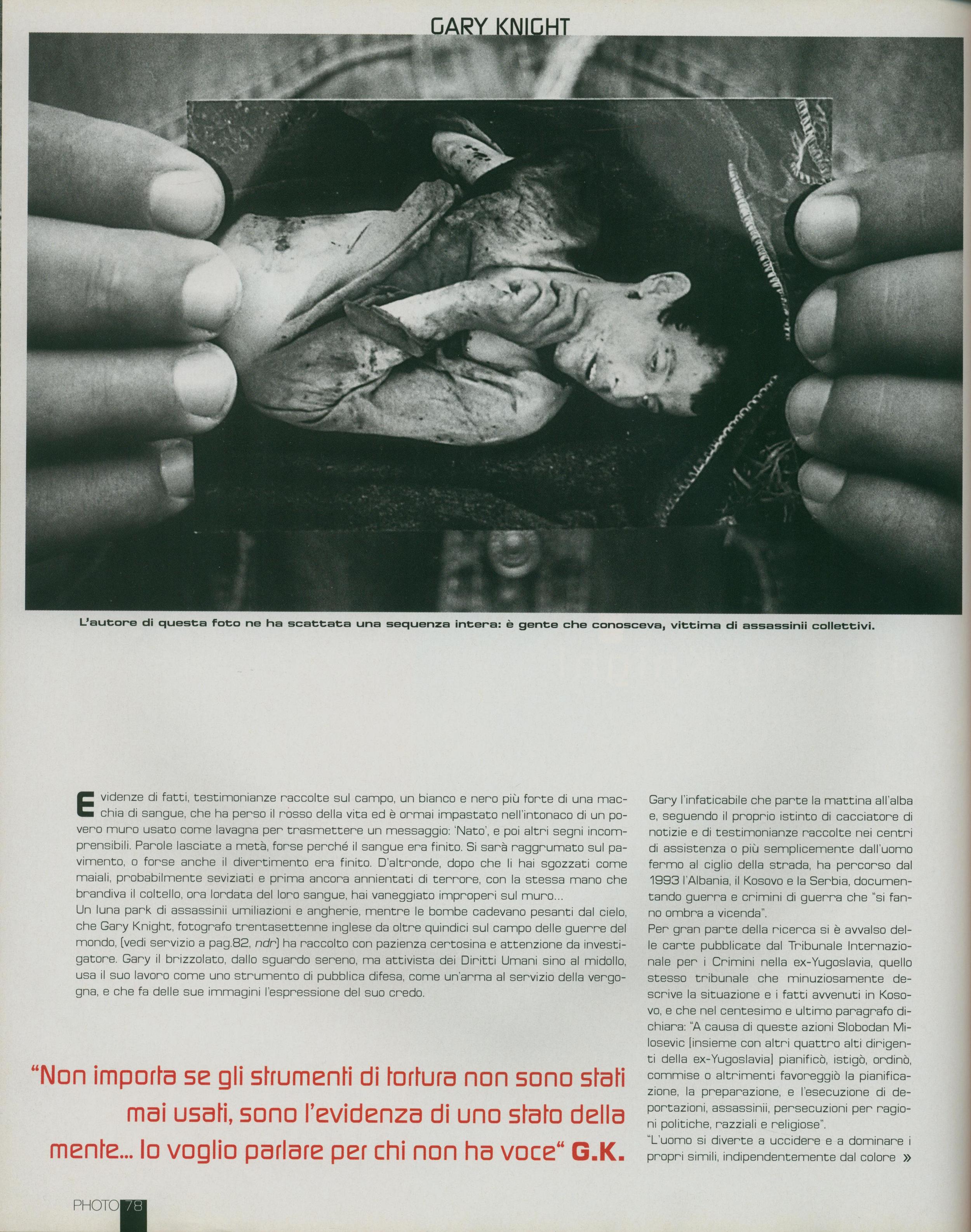

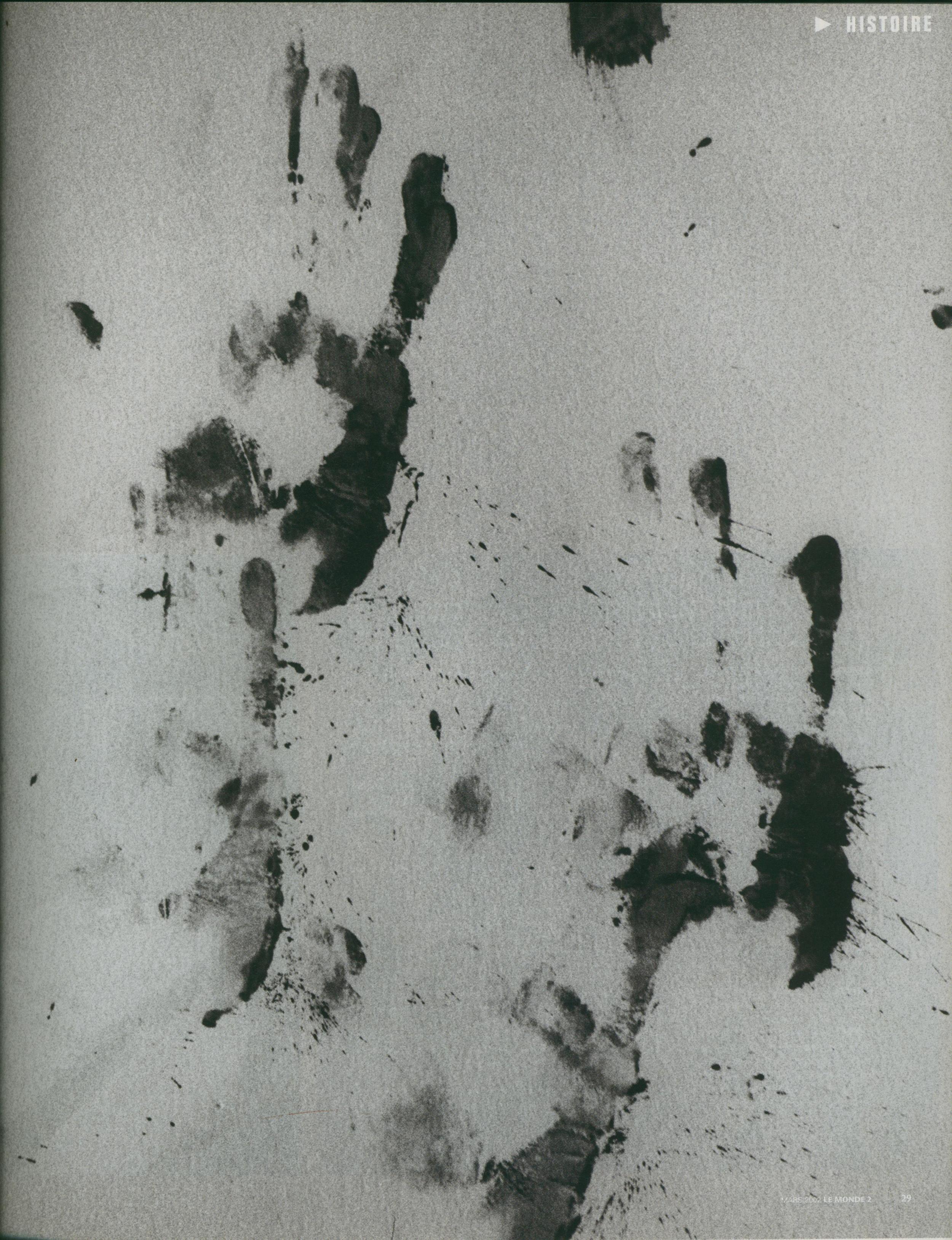

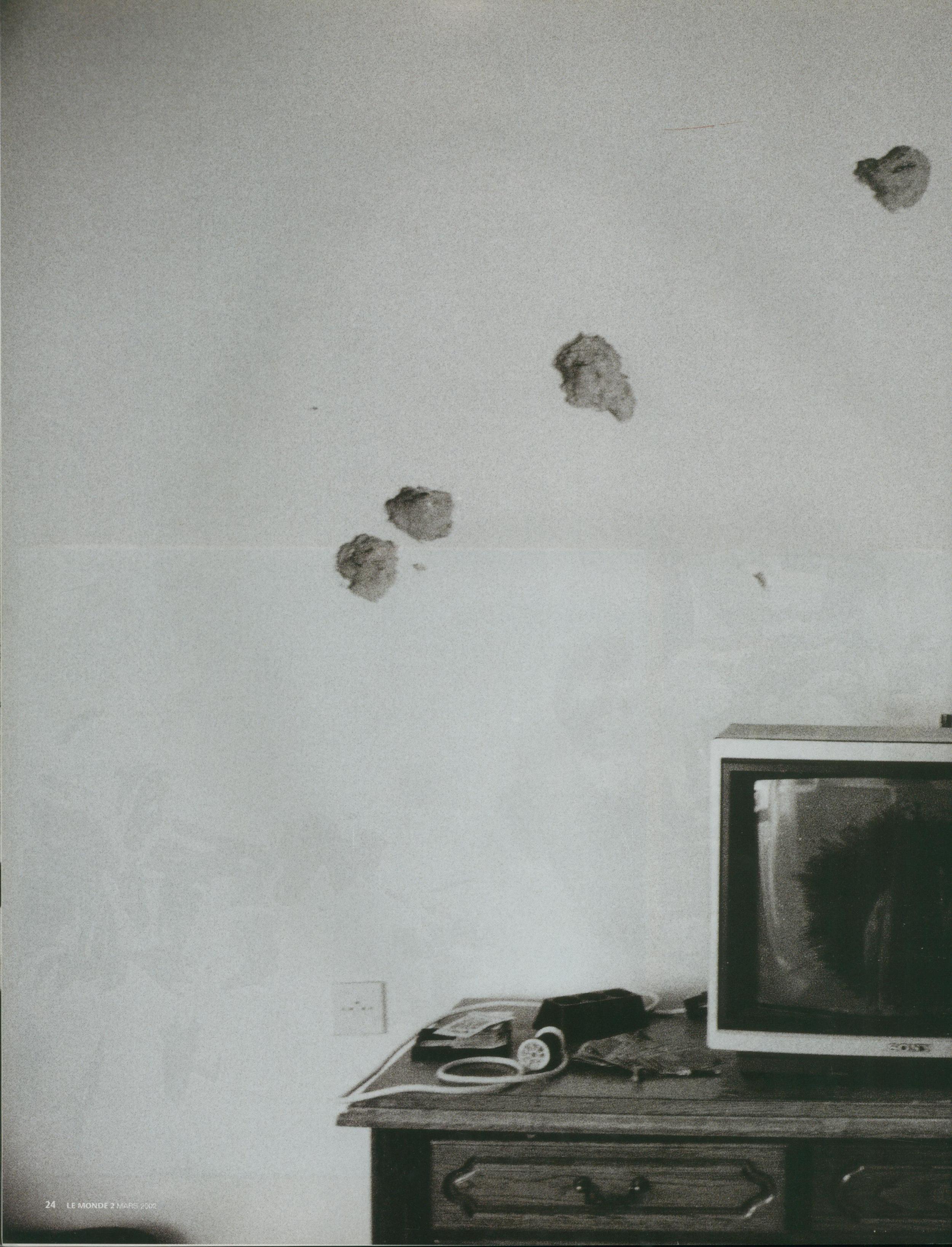

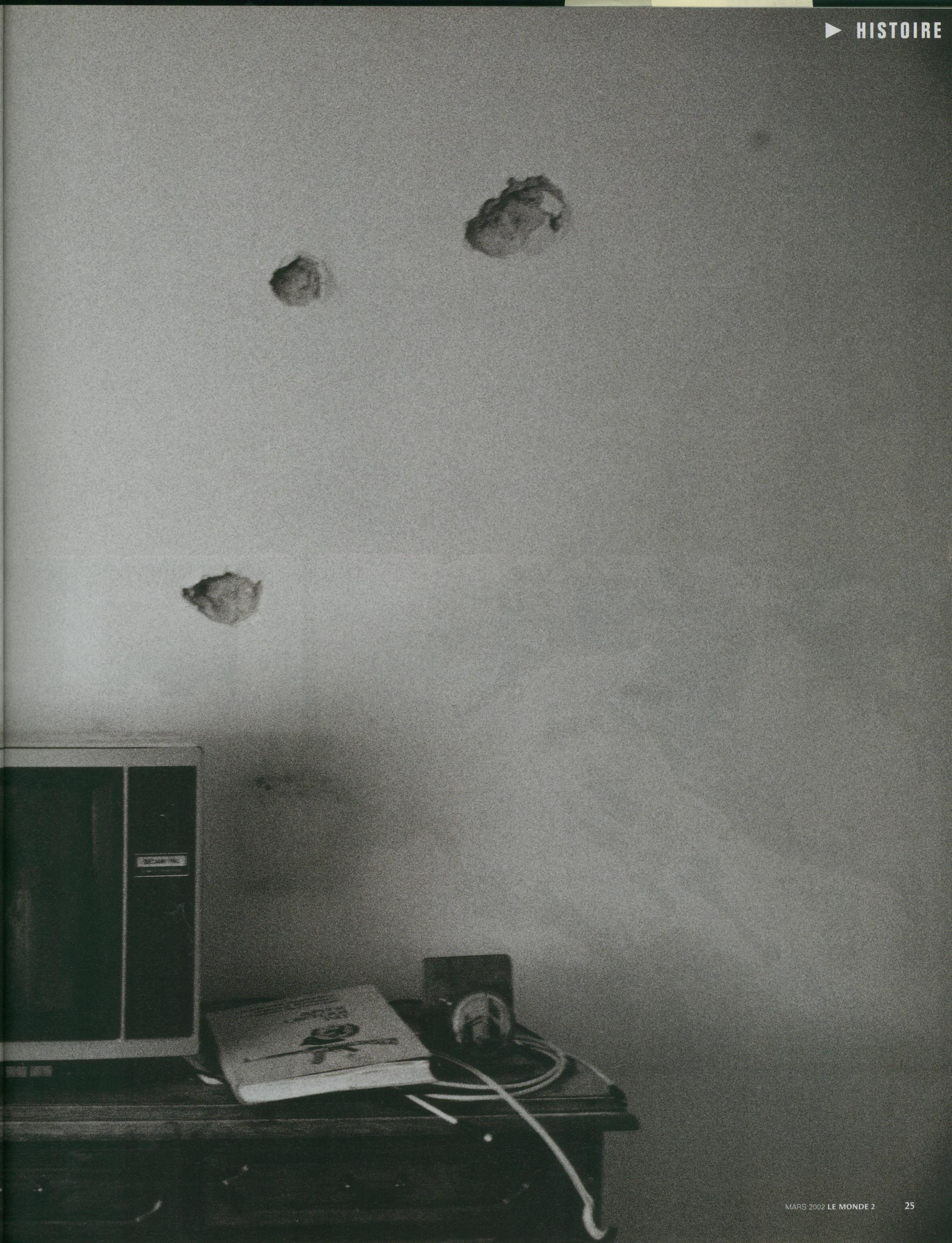

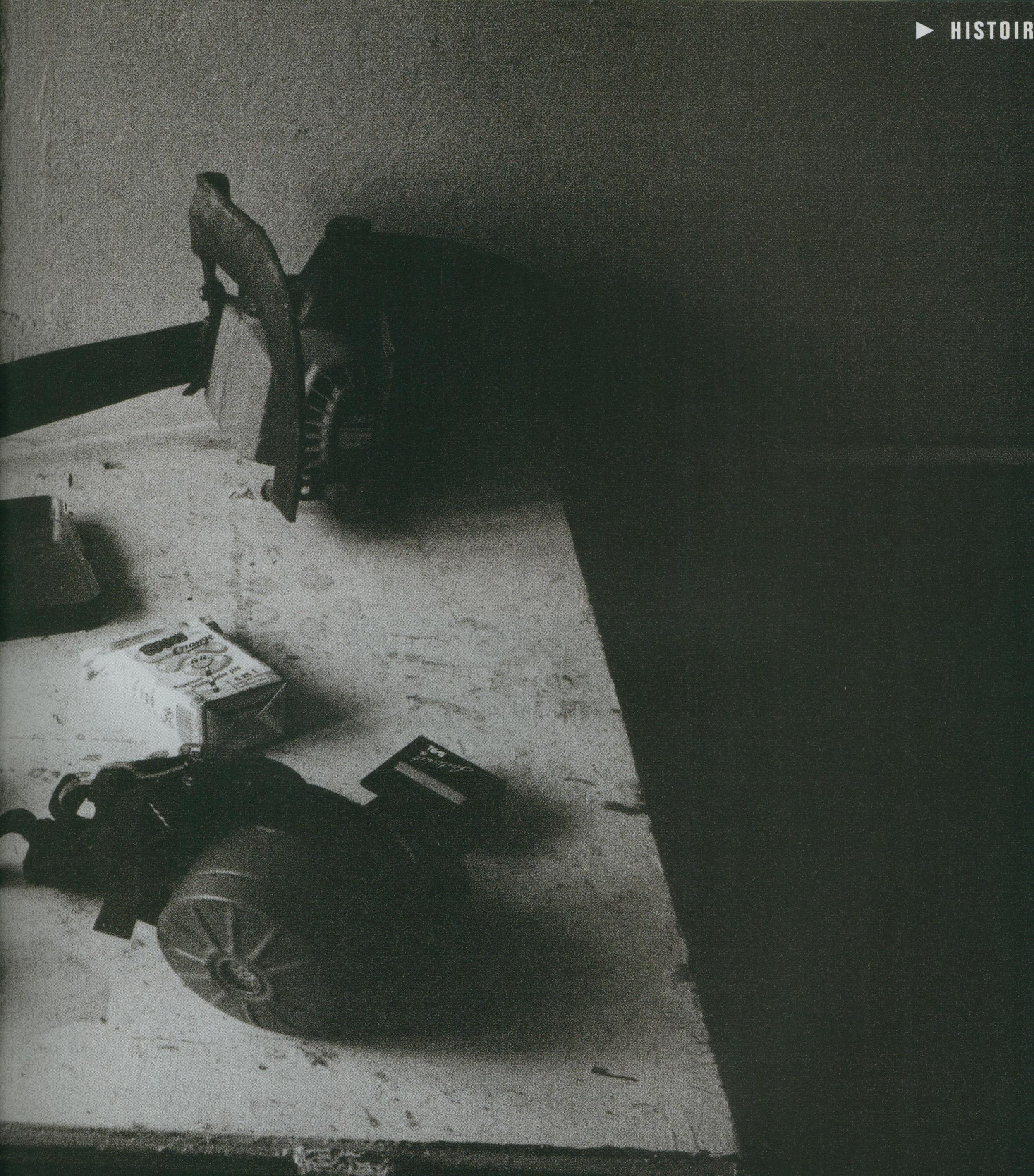

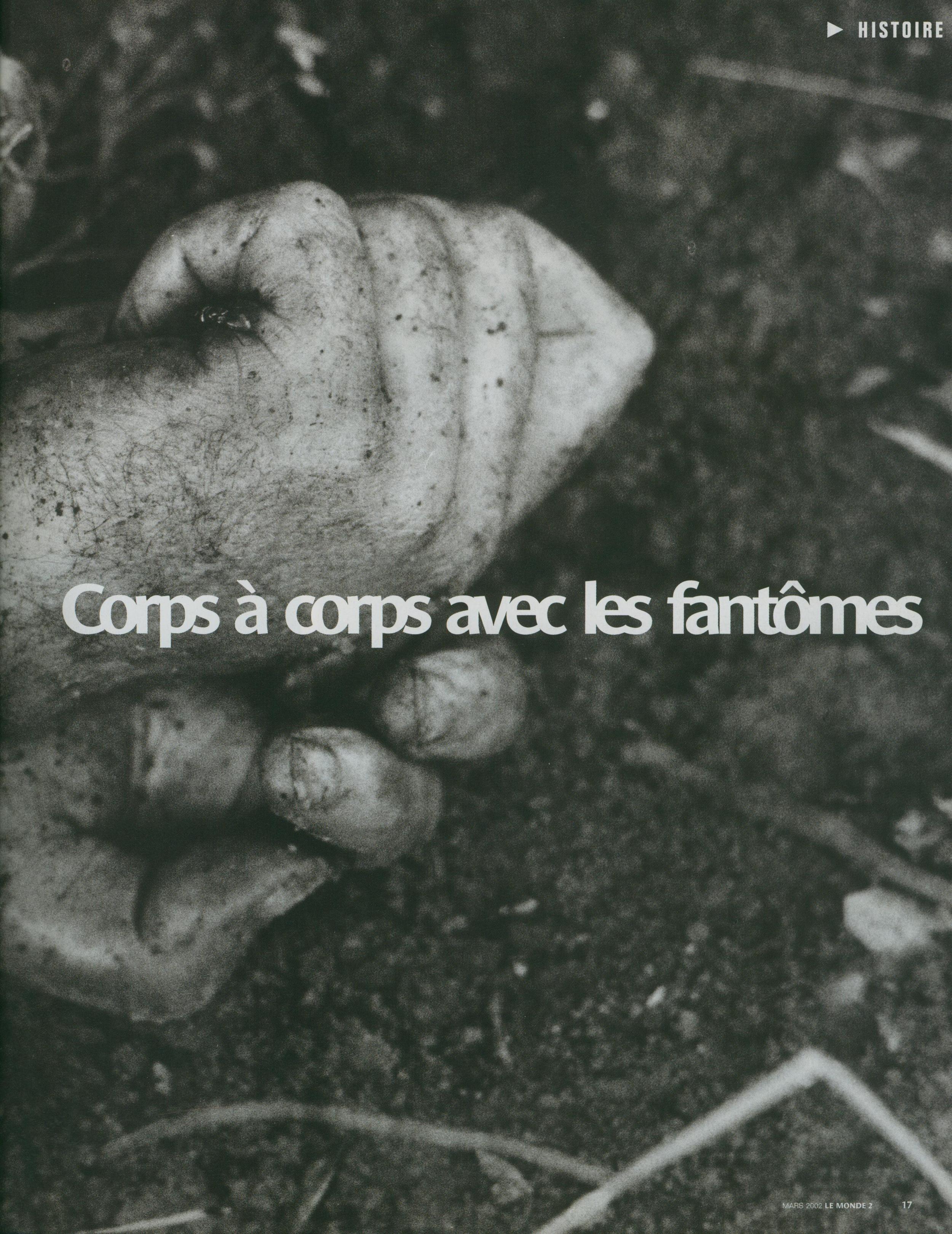

The outline of the body of Kola Dusmani, who according to criminal investigators, was killed by Russian para-militiaries in a small village outside the ancient market town of Gjakove. After he was murdered, the house where the crime was committed was burned. Soot and ashes covered the body. After the war was over and the family that owned he home returned, they removed Dusmani's remains from their living room. This outline could not be removed. Today it is concealed by a carpet.

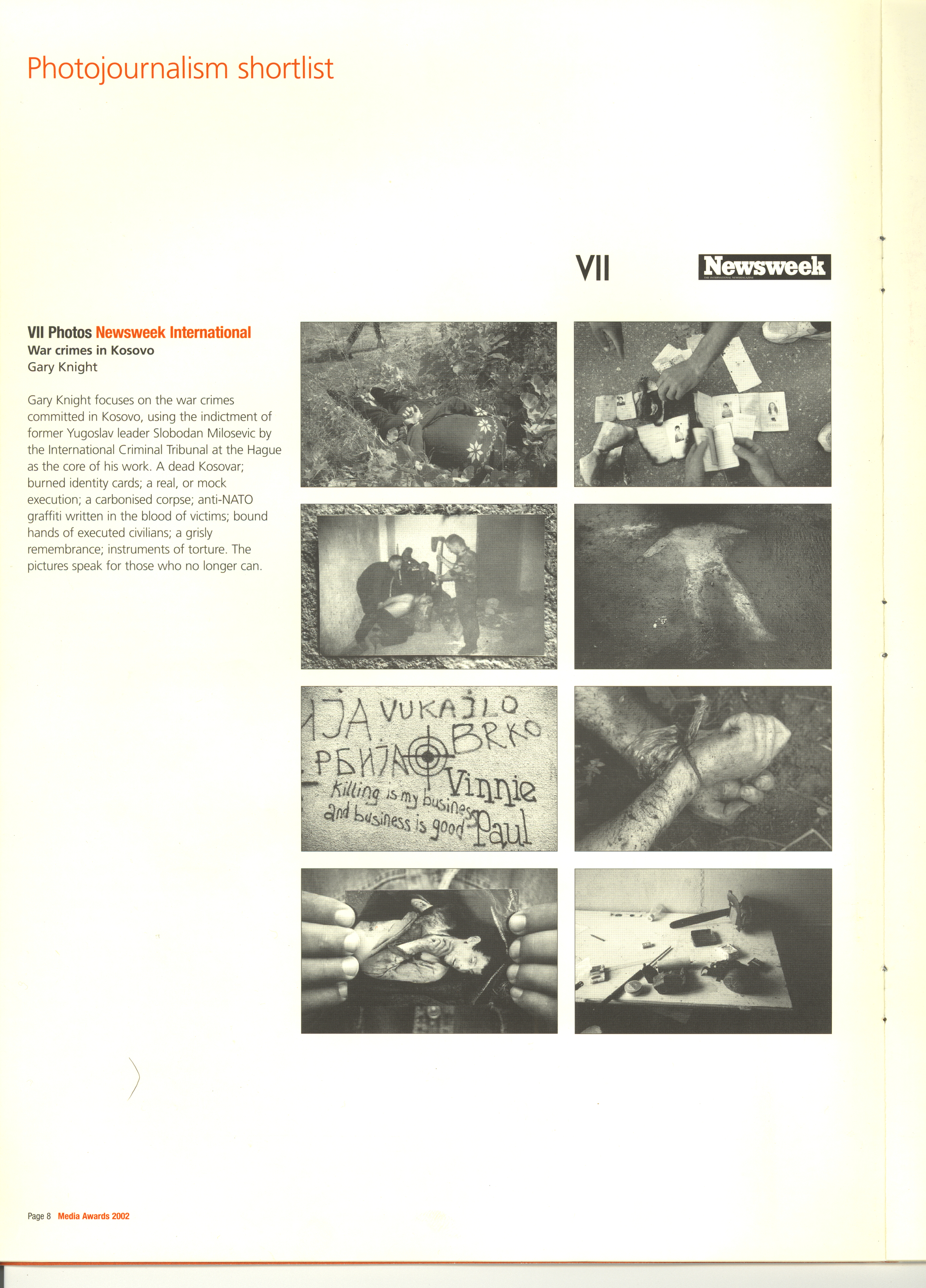

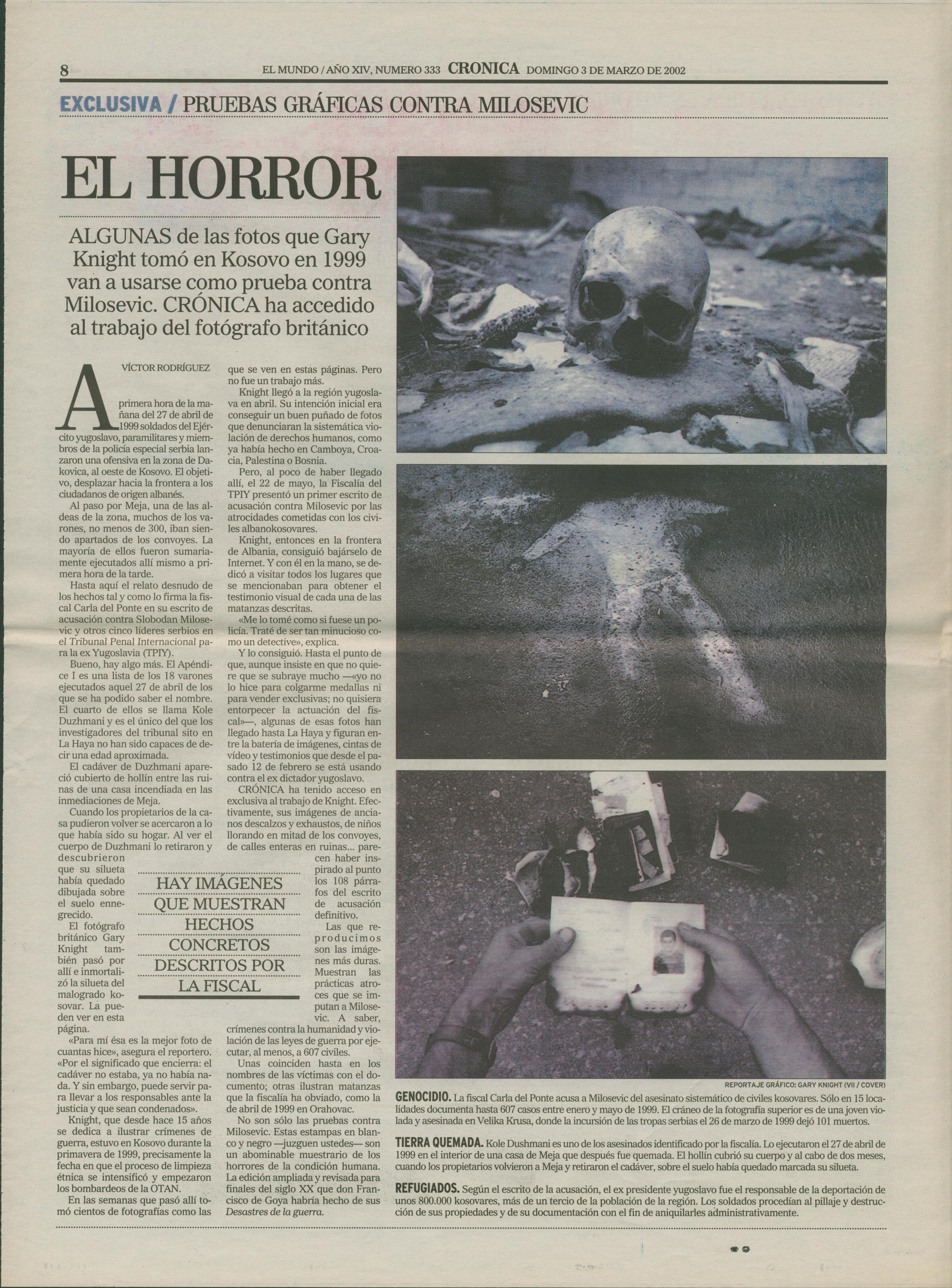

Evidence: War Crimes in Kosovo

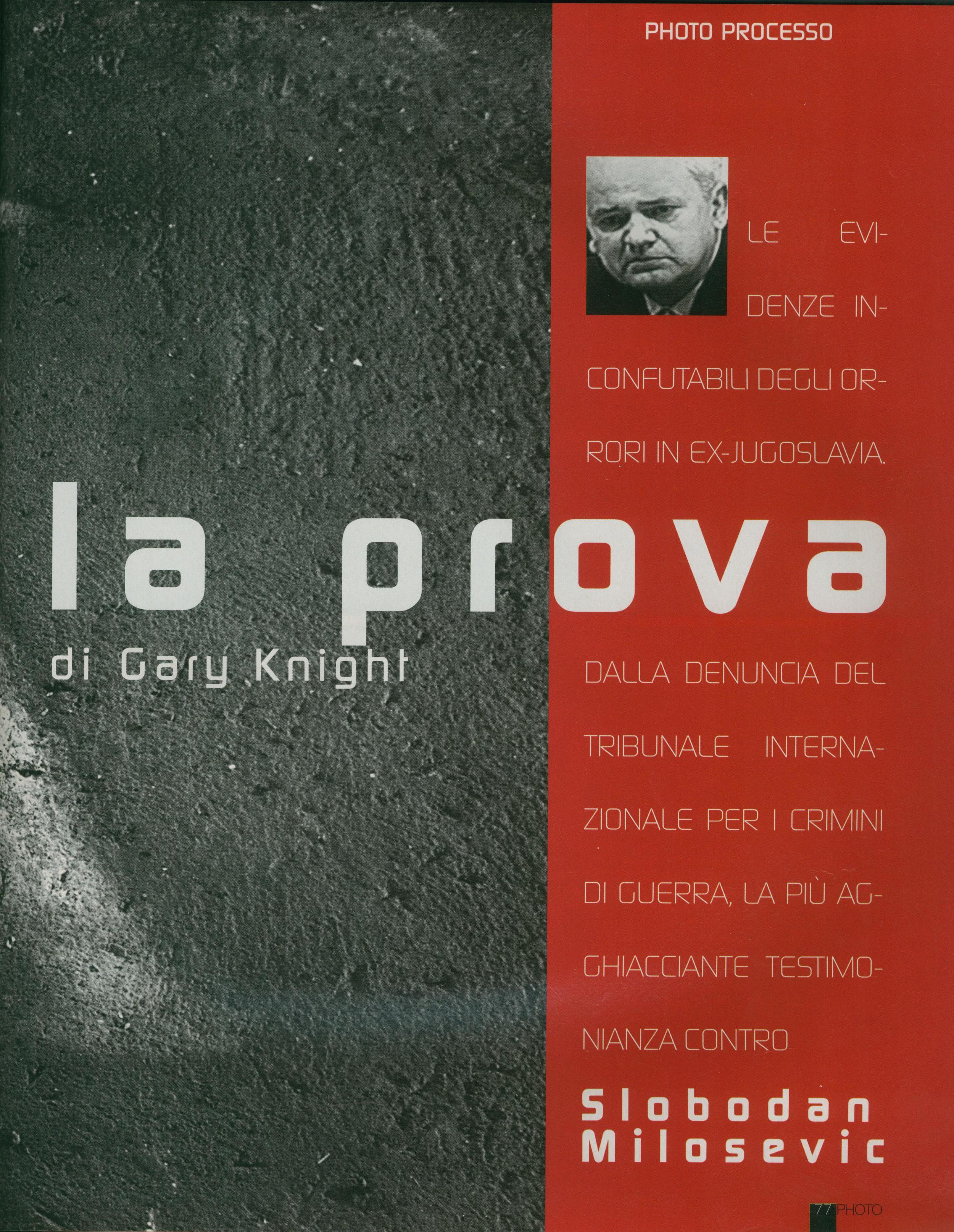

“Evidence: War Crimes in Kosovo,” is a body of work produced in Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo between February and July 1999. This work was a deliberate effort to address the issue of war crimes and was my first attempt to construct a documentary project in a war environment. Up until this moment, I had always worked on weekly journalism projects.

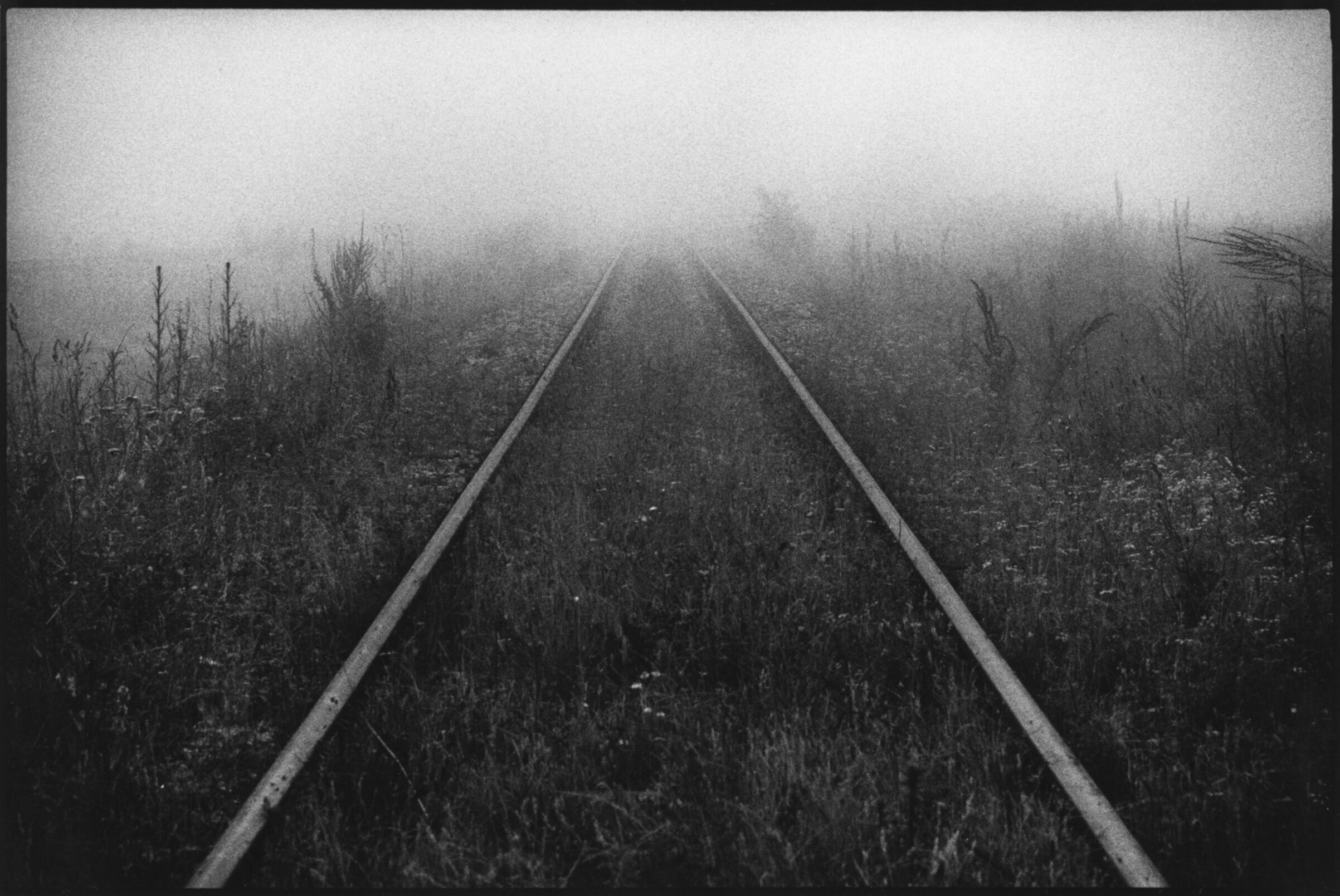

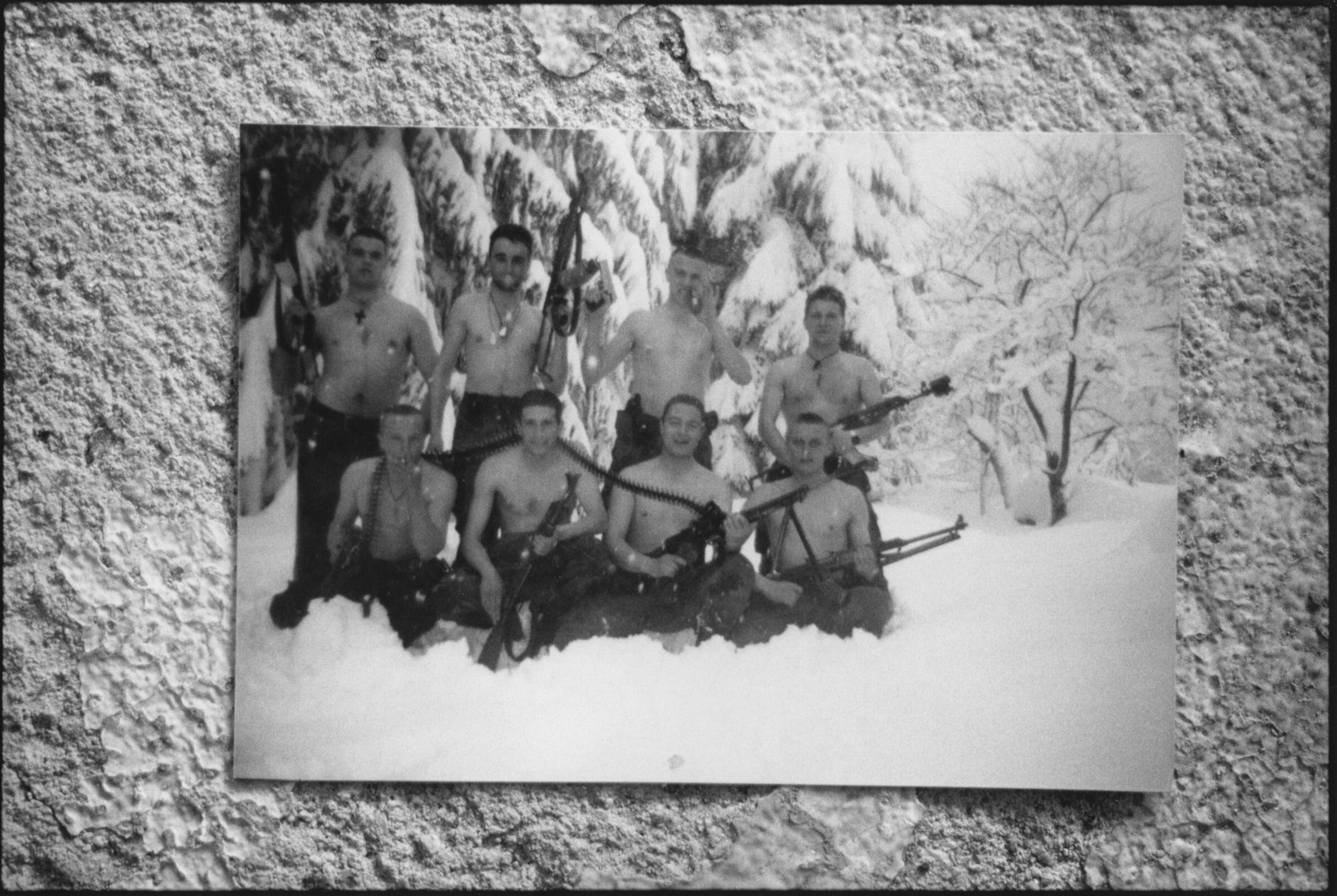

I had photographed the war in Bosnia from January 1993 until it ended in December 1995 and continued to photograph its aftermath through the late 1990s. My work in Bosnia was driven by news events and the demand for imagery from media clients in the USA and Europe. By the time the war ended, I felt I’d fulfilled my obligation to my clients but had failed to address directly what I saw as the critical issues of the war—crimes against humanity and war crimes. During that war, I established a friendship with photographer Gilles Peress, who had a significant impact on the way I approached my work. We were frequent traveling companions during the violent years in the former Yugoslavia, where Gilles challenged me to use my photography with greater urgency and militancy and to explore the remote areas beyond the boundaries of my experience and imagination.

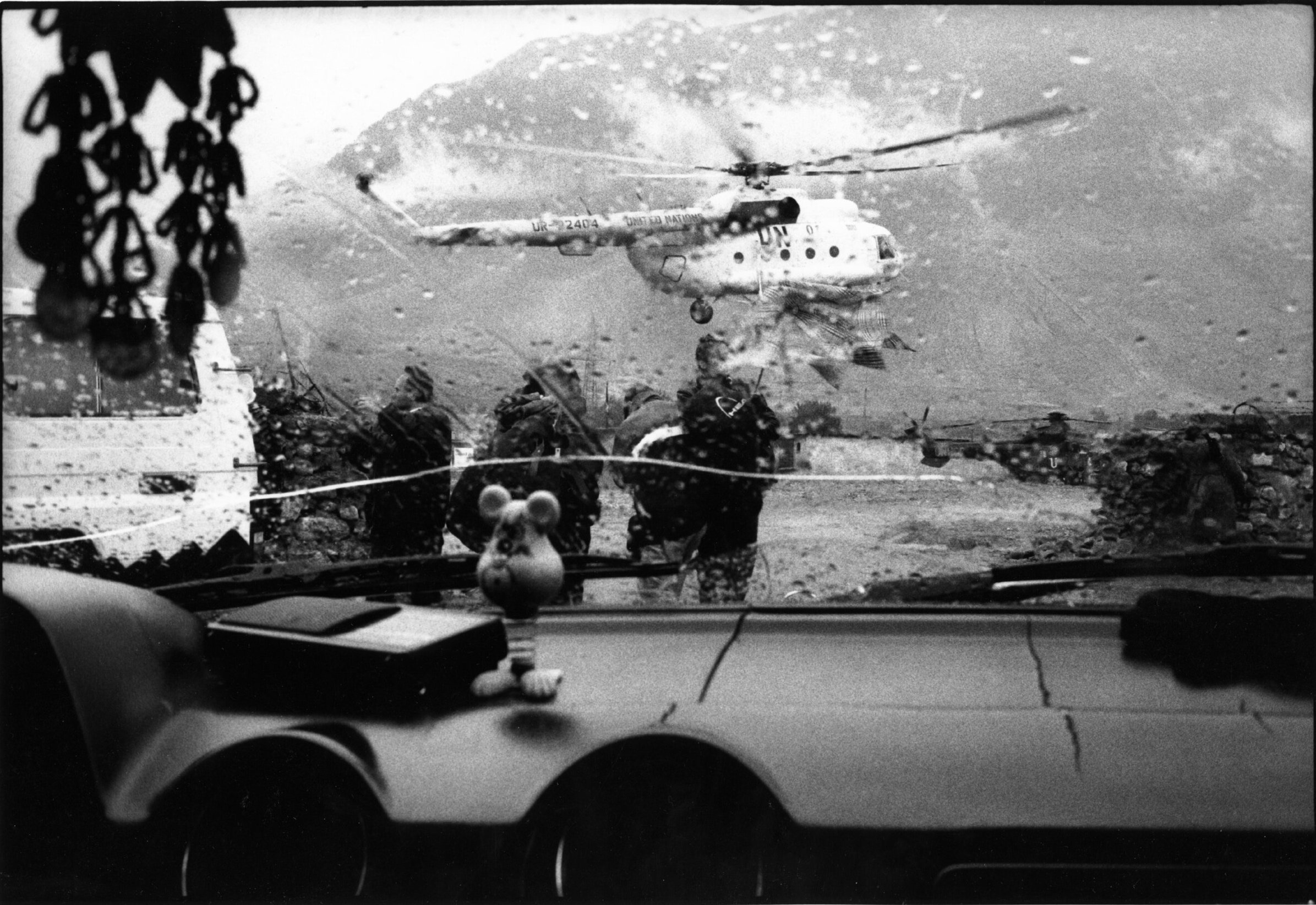

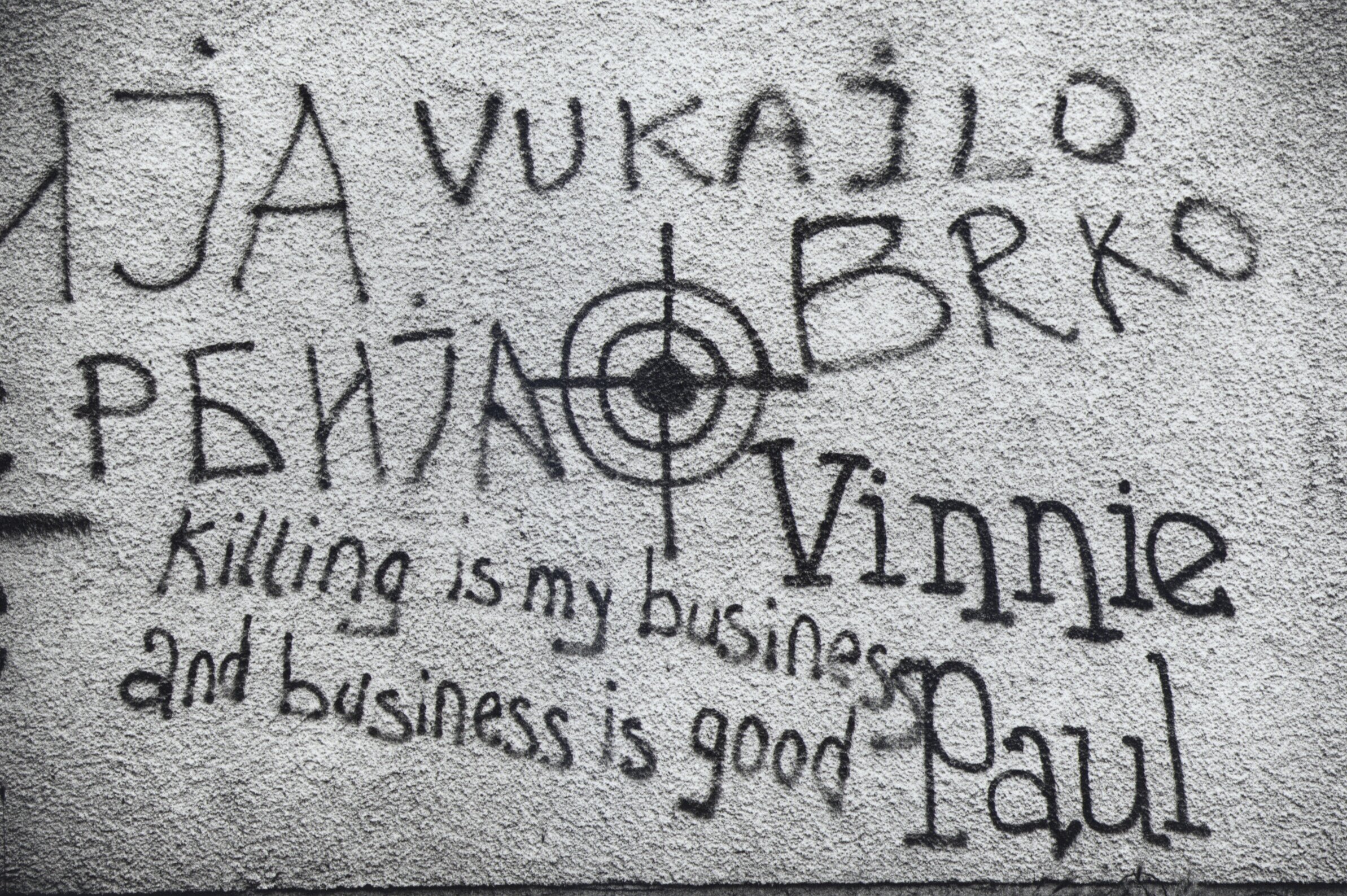

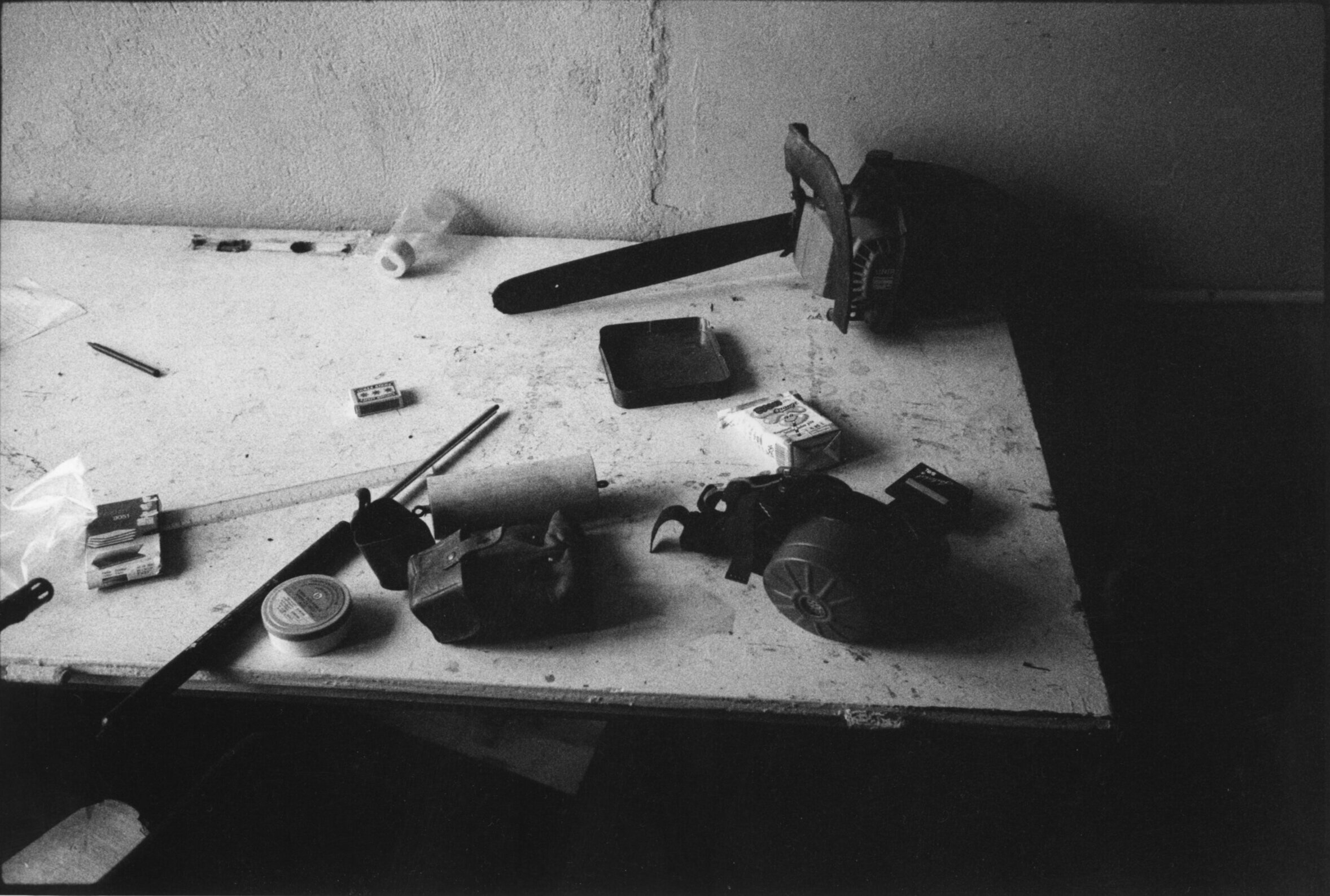

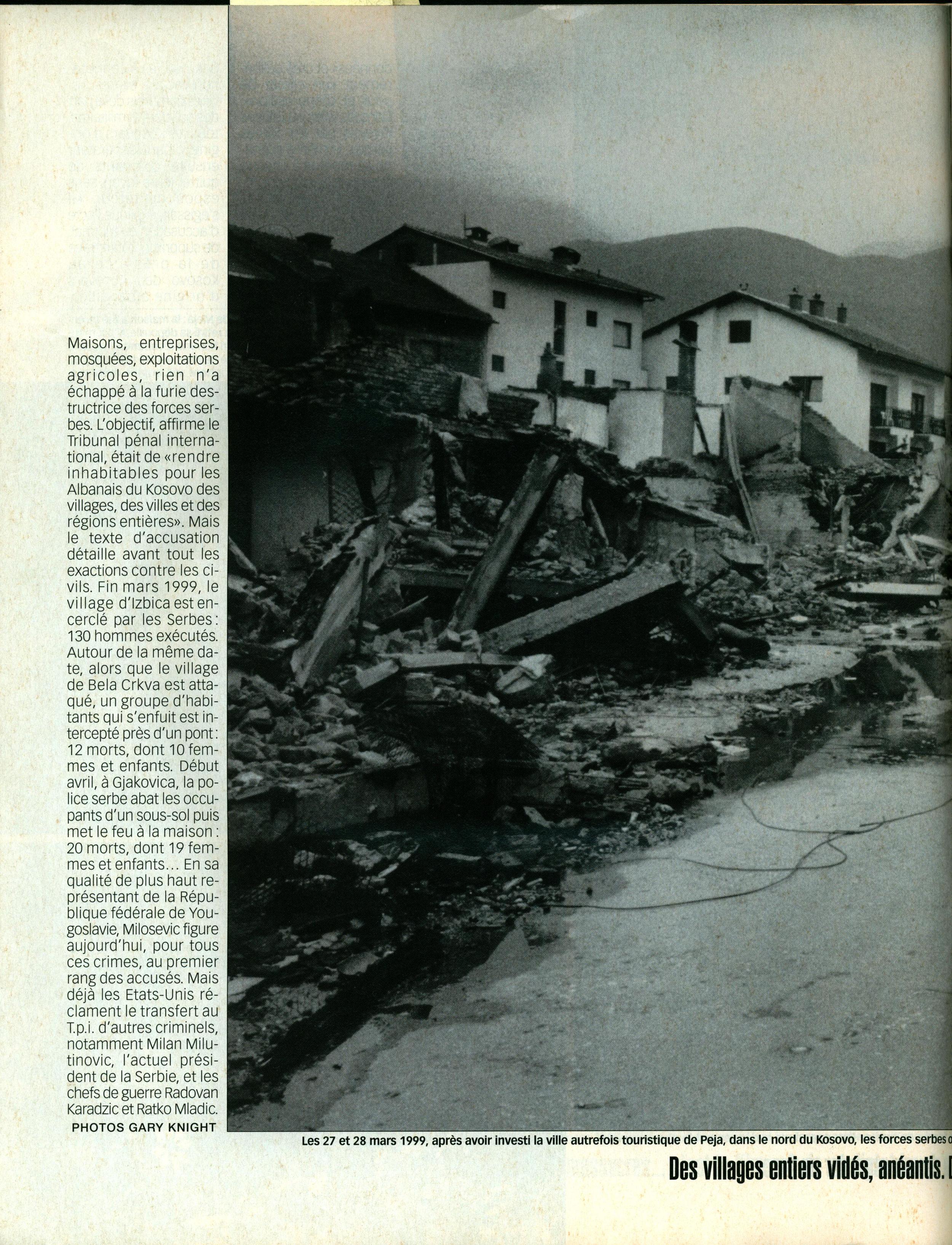

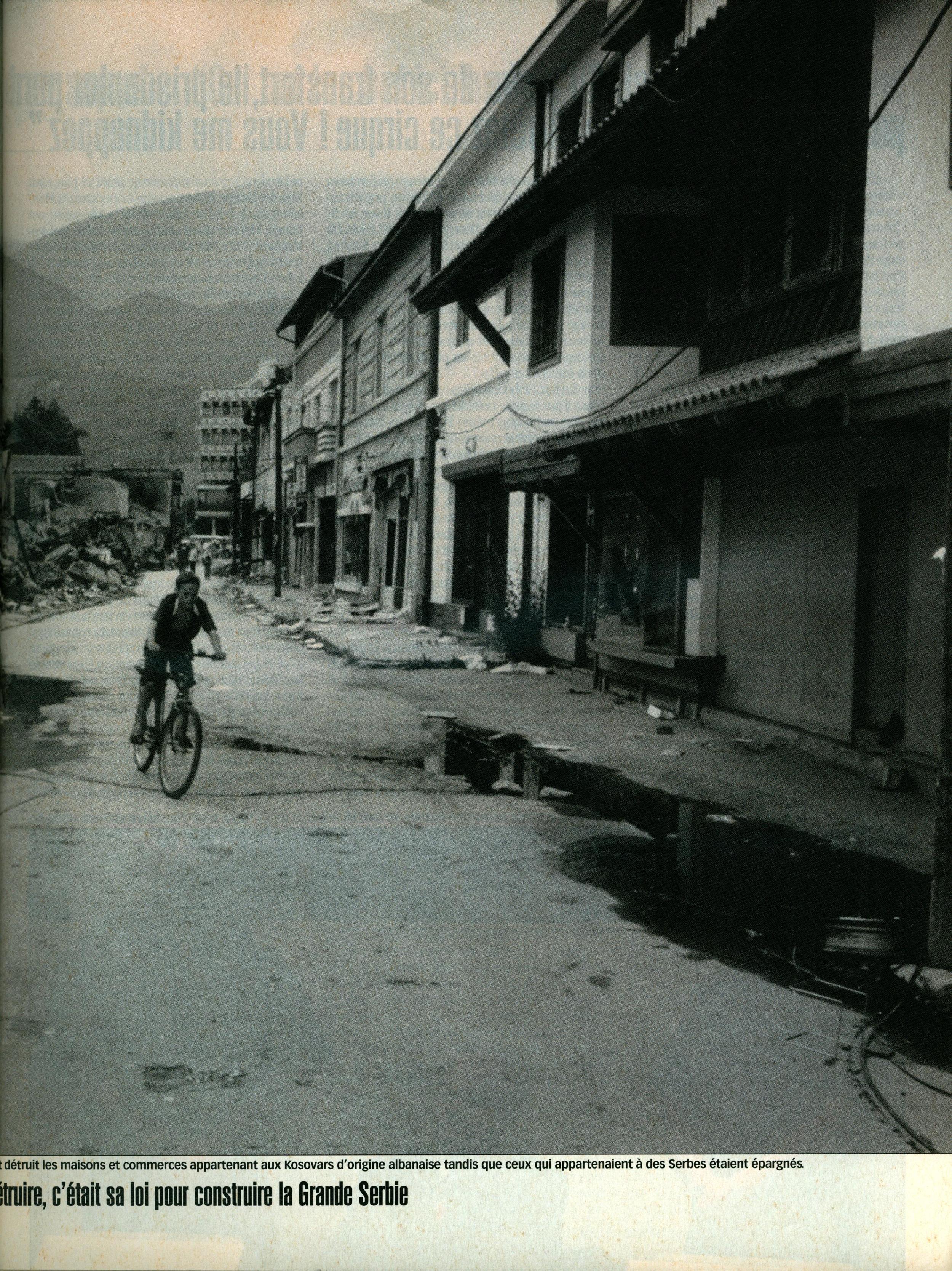

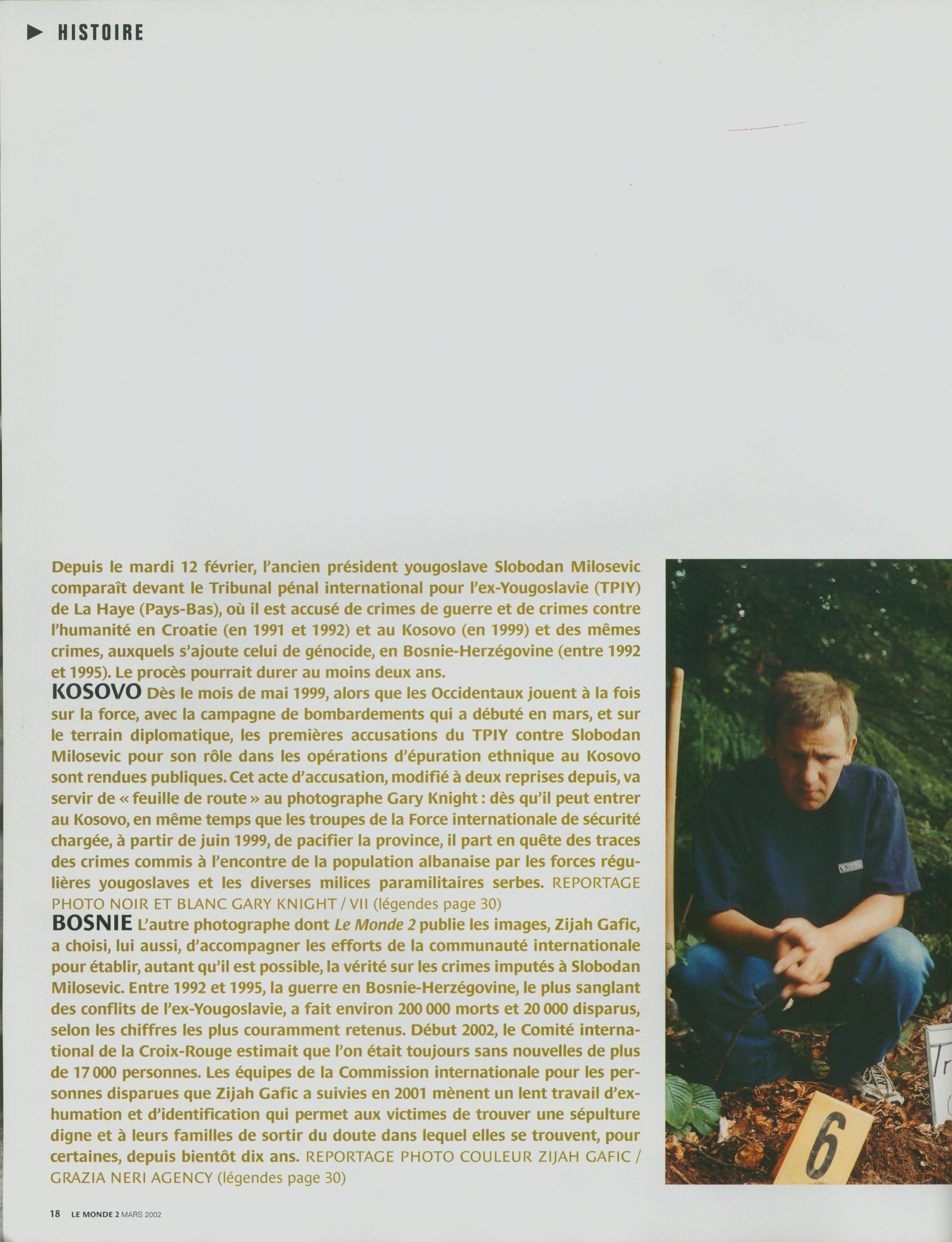

The war in Kosovo was the final act of dismemberment of Yugoslavia, a vicious endgame. It was evident during the prelude to the war that the pattern of murder, rape, deportation, and persecution the world had witnessed in Bosnia was being revisited by military or paramilitary forces loyal to the Republic of Serbia on what it considered to be a subjugated civilian populace. I agreed with my editors at Newsweek, Charles Borst, and Guy Cooper, and with my longtime collaborator, Newsweek correspondent-at-large Rod Nordland, that I would focus my work on the issue of war crimes from the beginning of our coverage of the story. What remained was to find a narrative structure. Gilles encouraged me to approach the story like an investigator (he seemed to think my family’s history in the British police gave me some useful genetic advantage). But how would I frame the project?

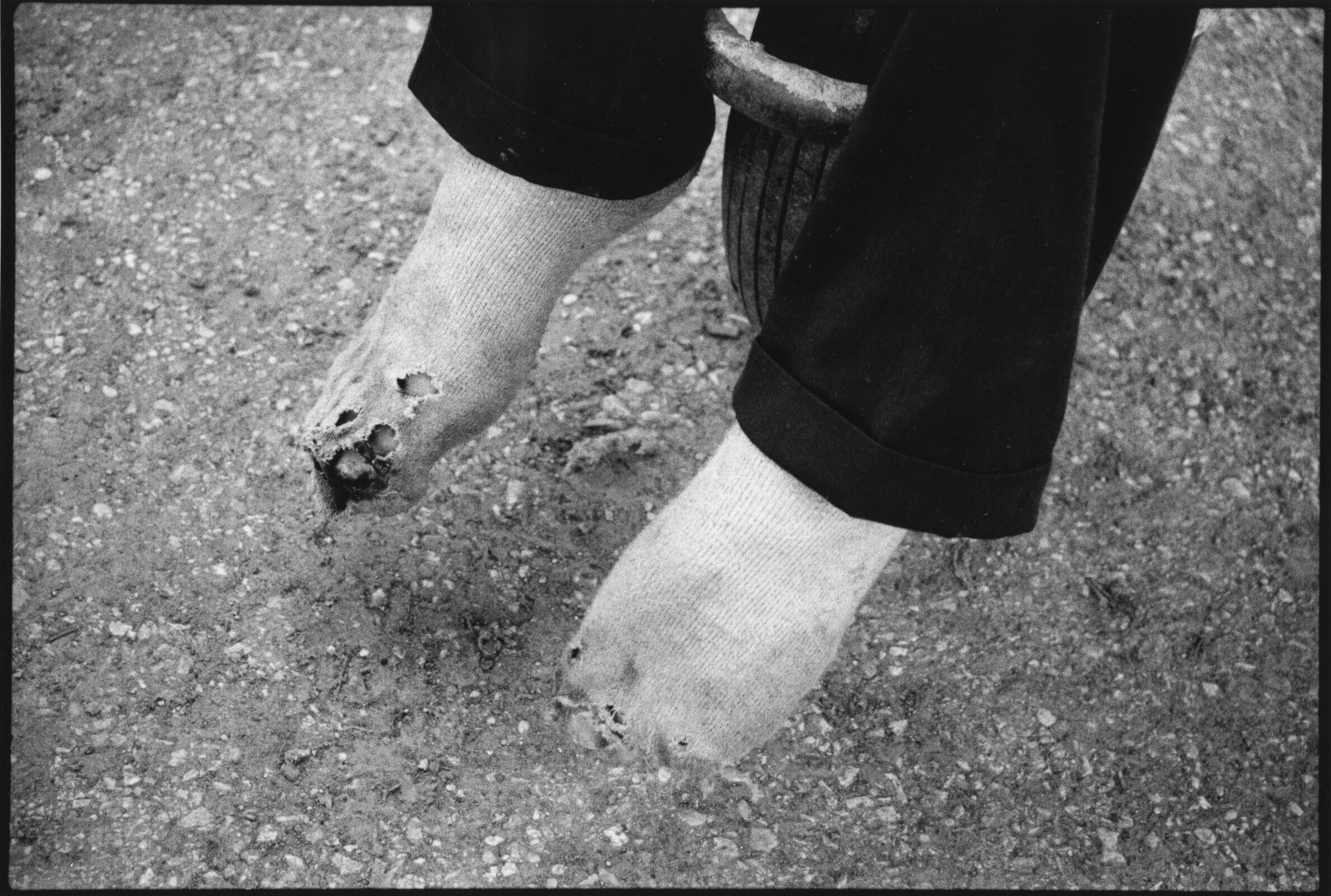

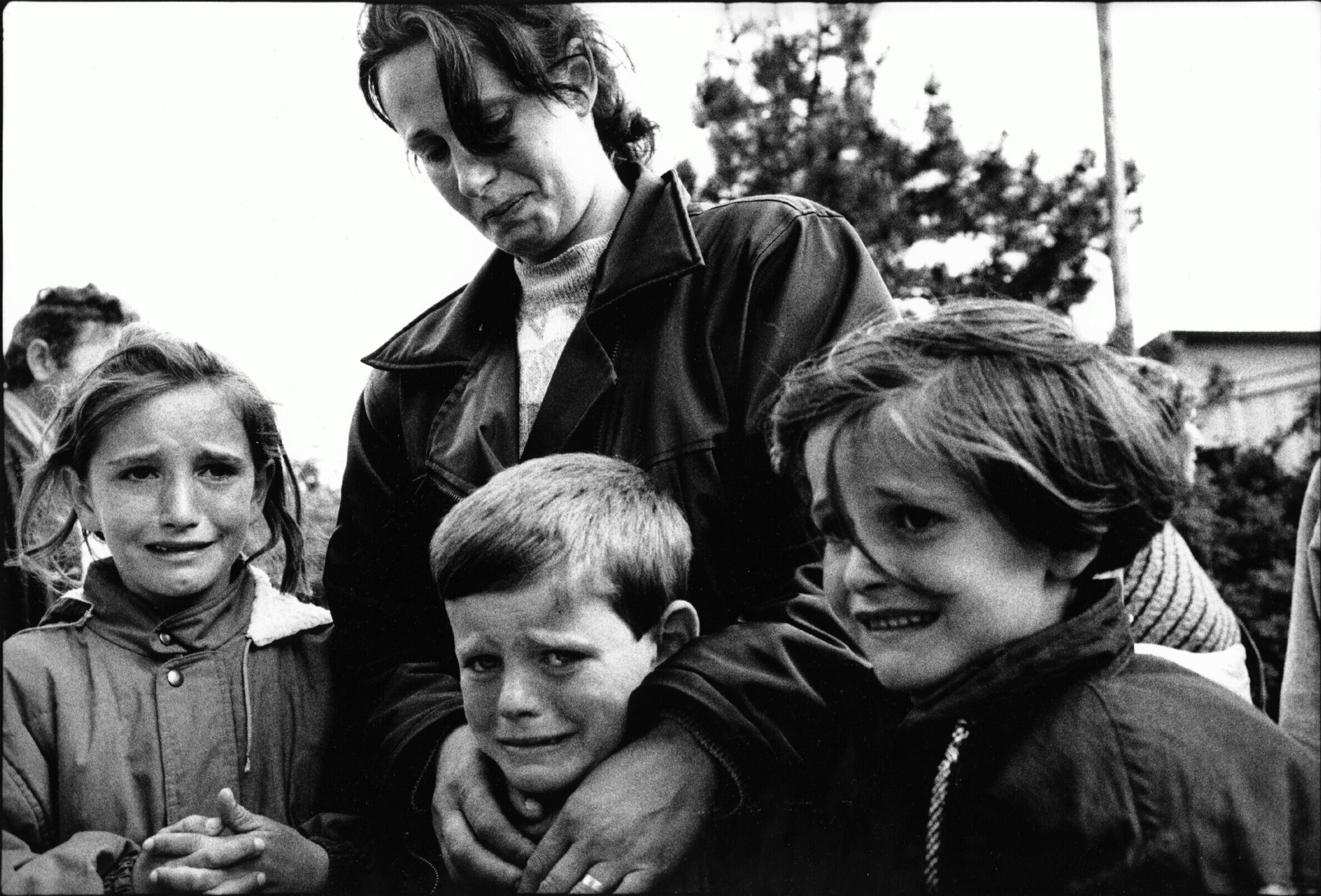

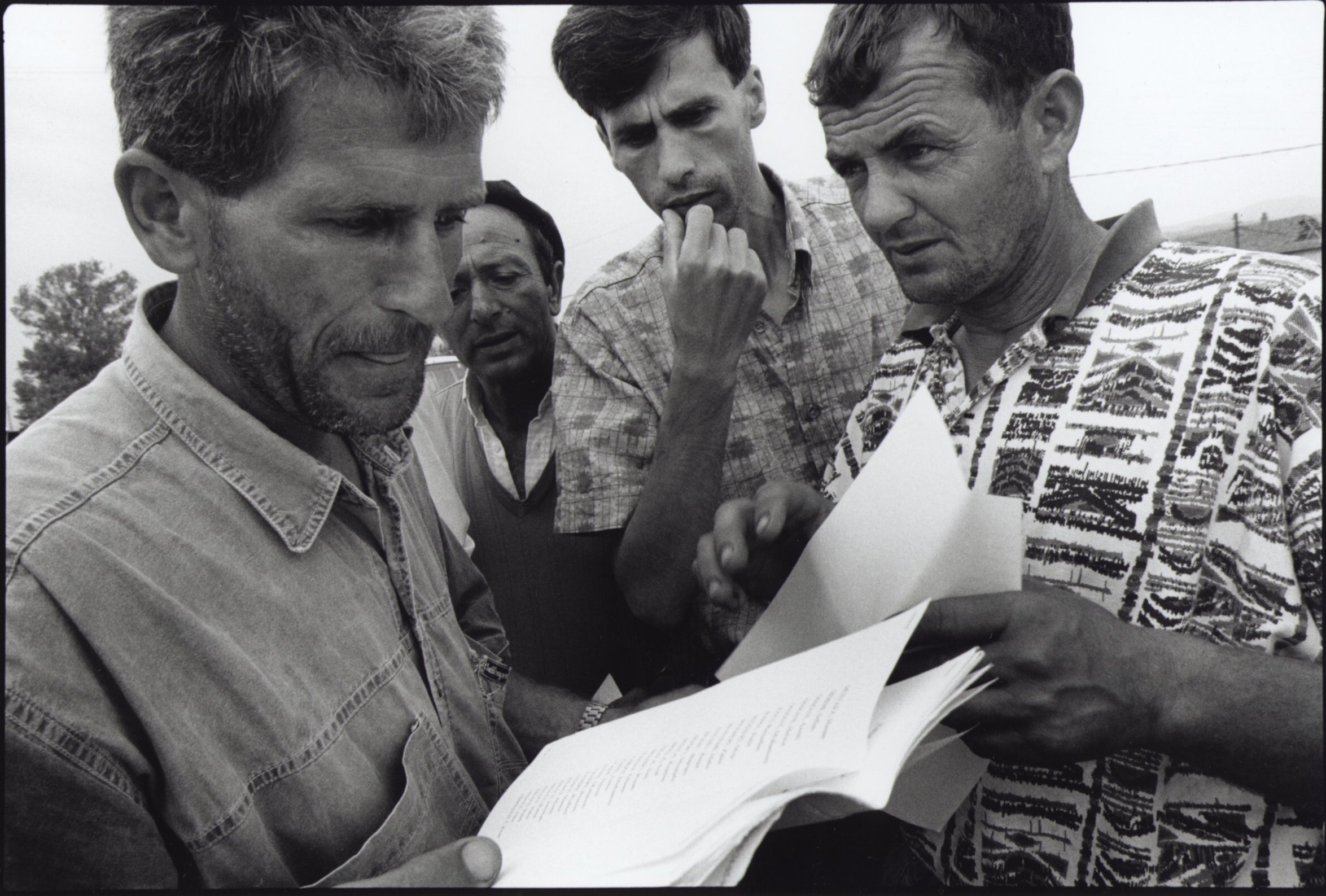

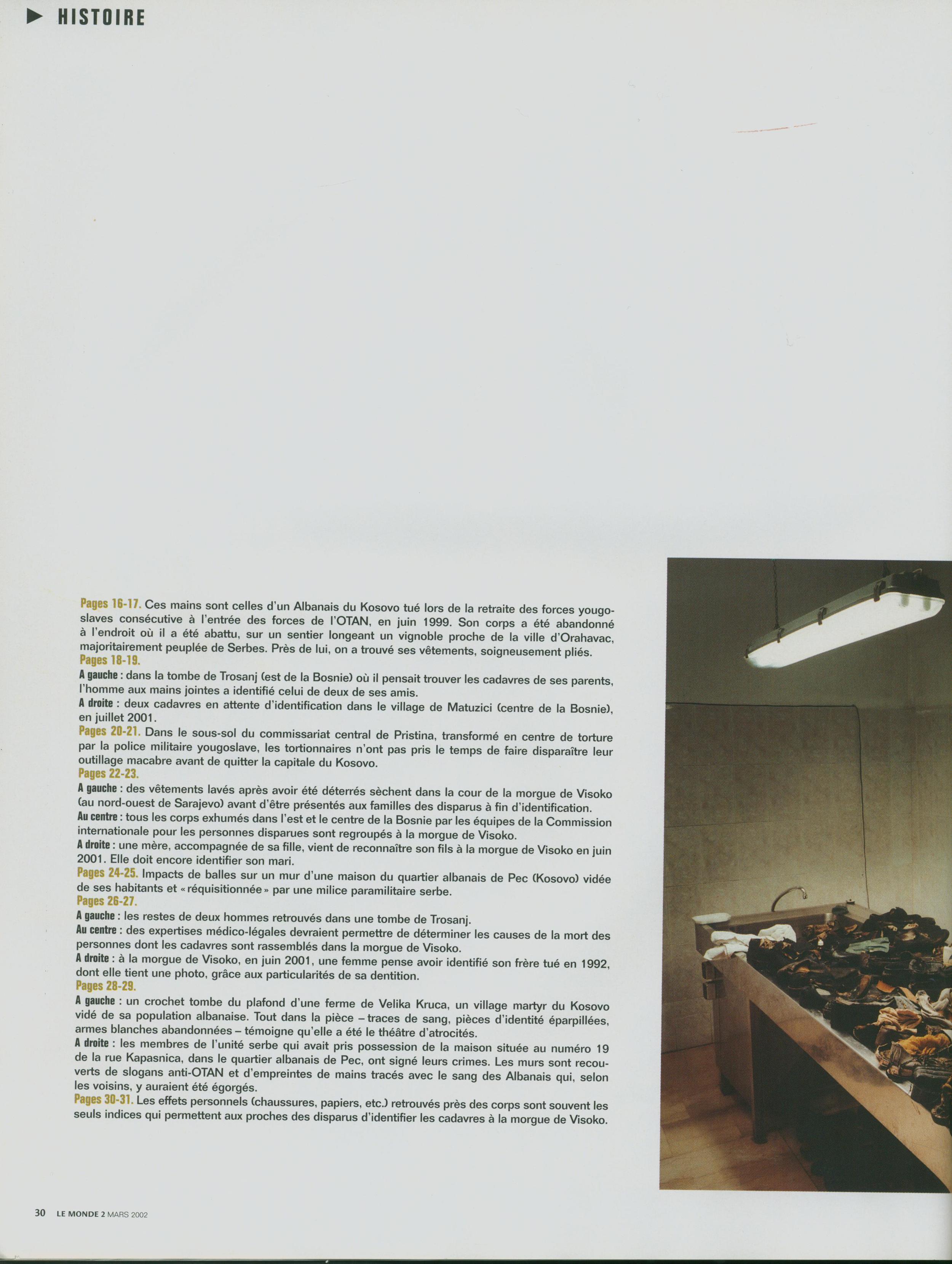

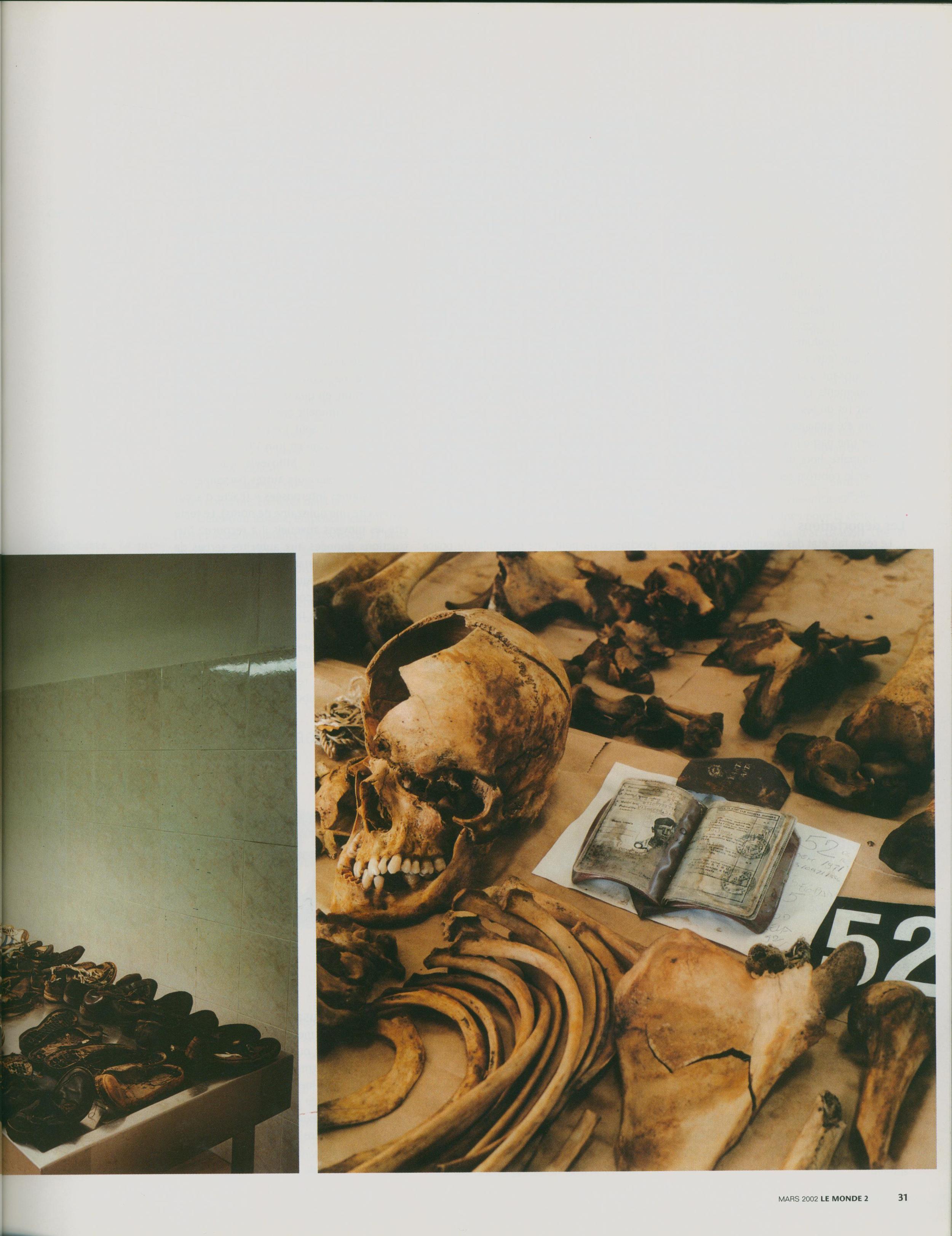

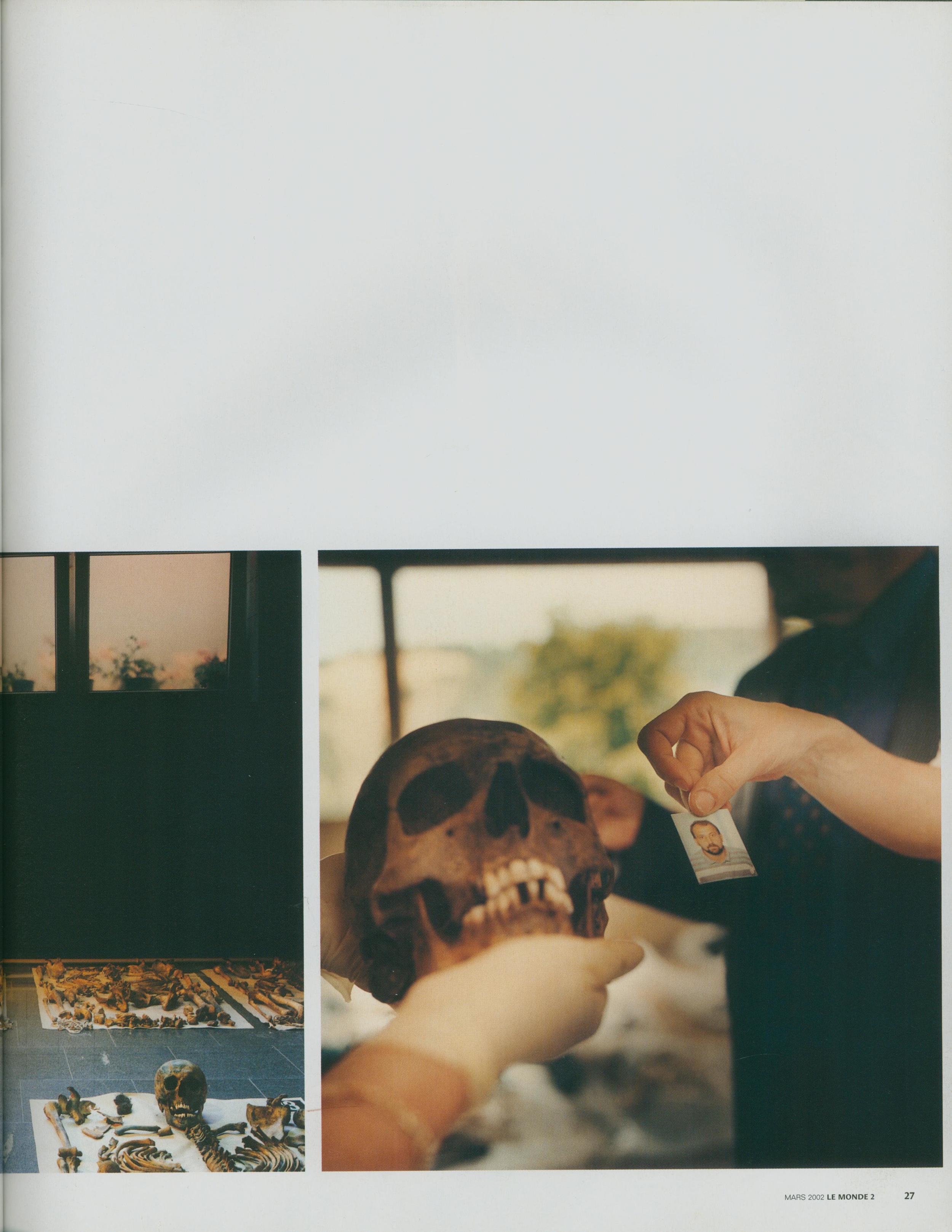

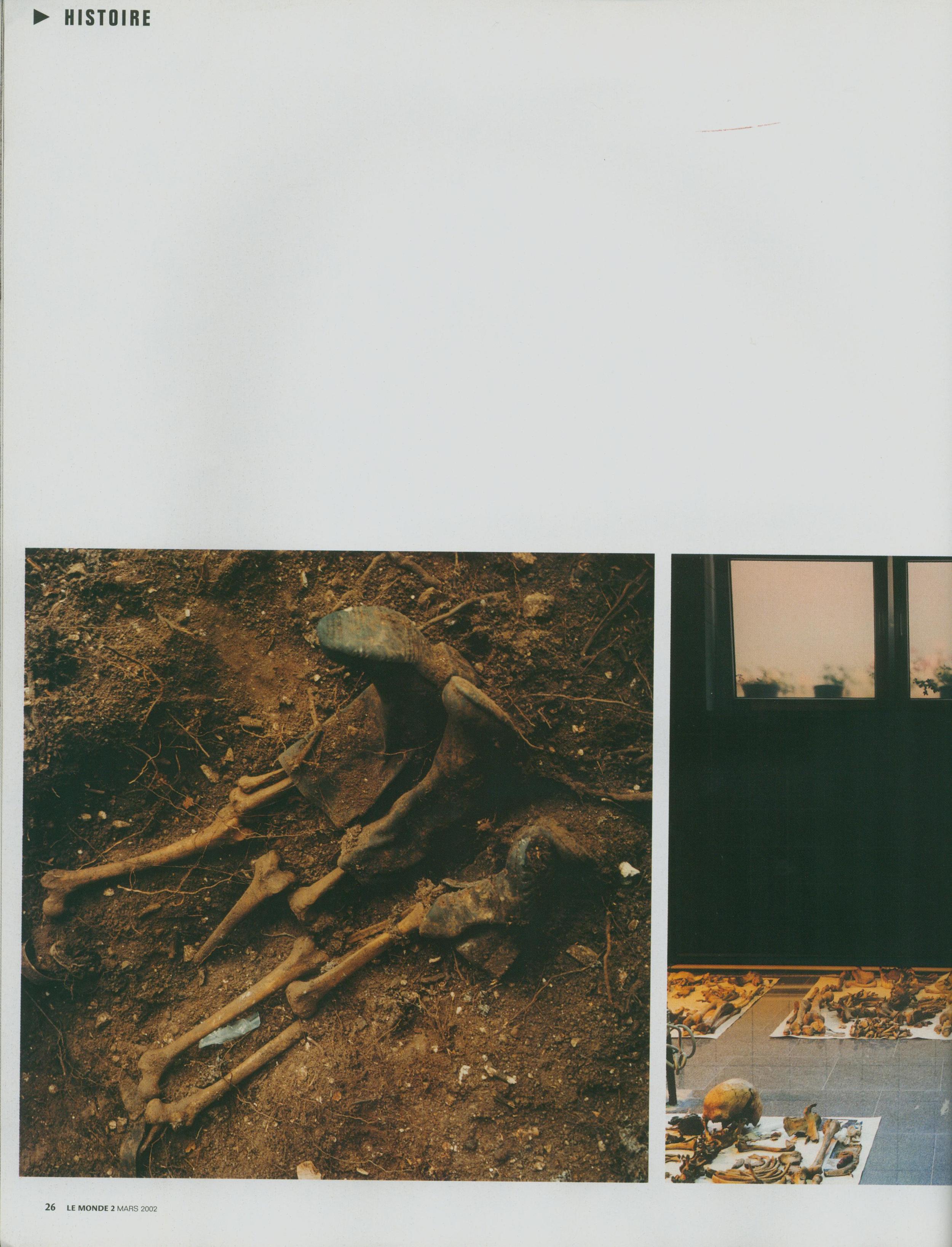

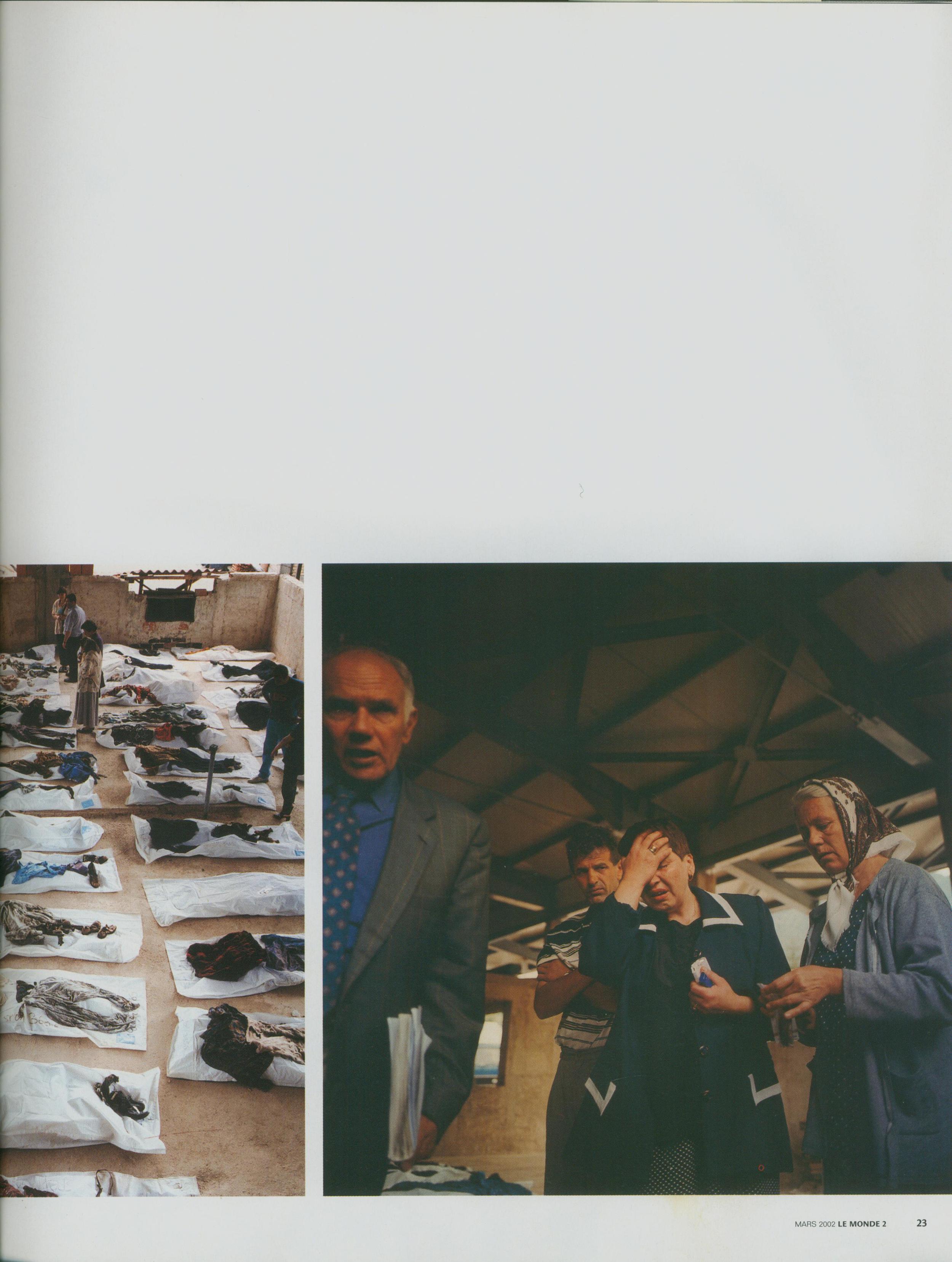

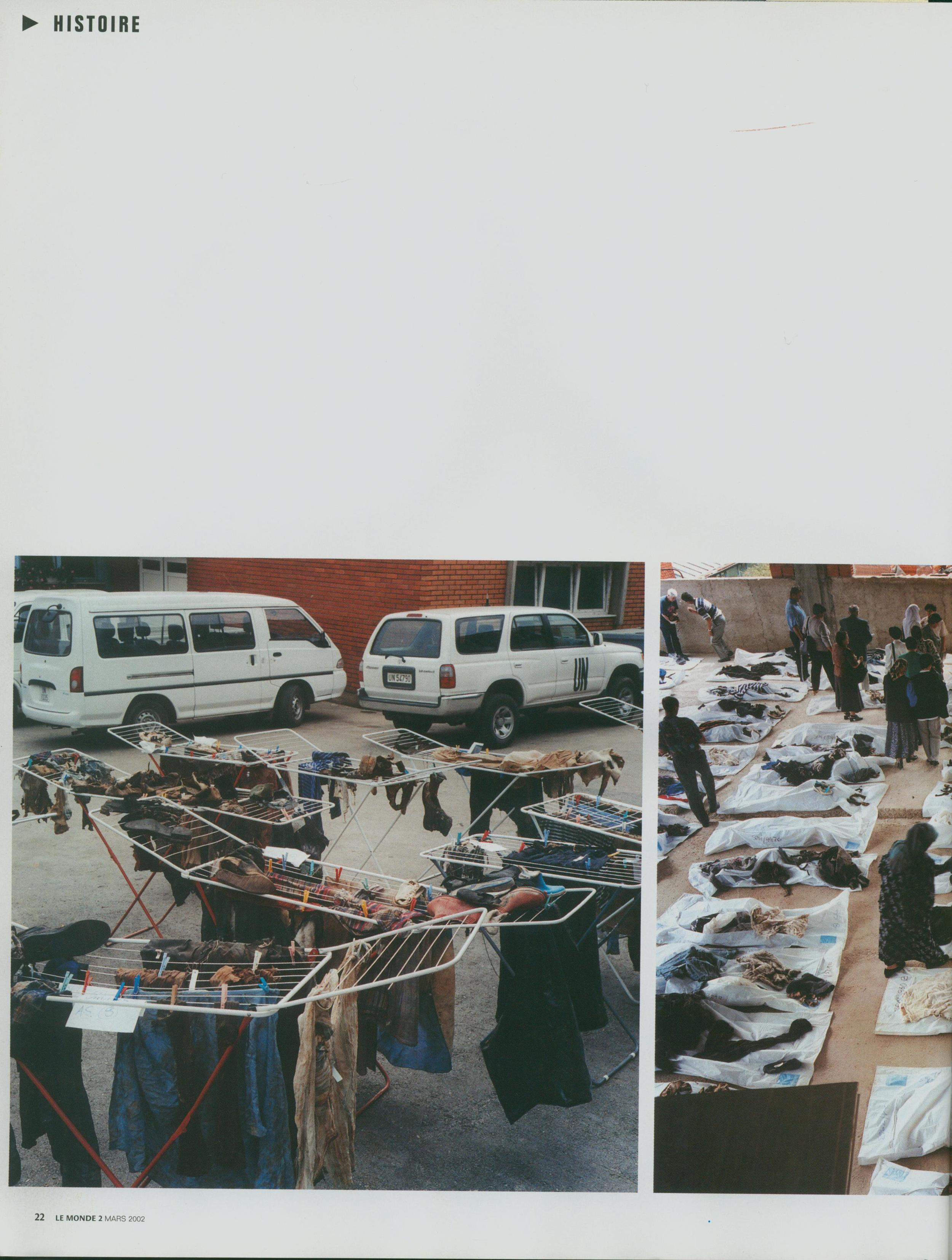

A few weeks after I arrived in Albania to start working amongst the displaced Kosovars fleeing Serb war crimes in Kosovo, a colleague from Newsweek acquired a copy of the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia’s indictment of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević and his collaborators. Once I read the indictment, I immediately understood that it provided the perfect structure for my project. The indictment notes every war crime in Kosovo and names the perpetrators, if known, the victims, and the locations of the crimes. It is divided into three parts: Deportation, Persecution, and Murder.

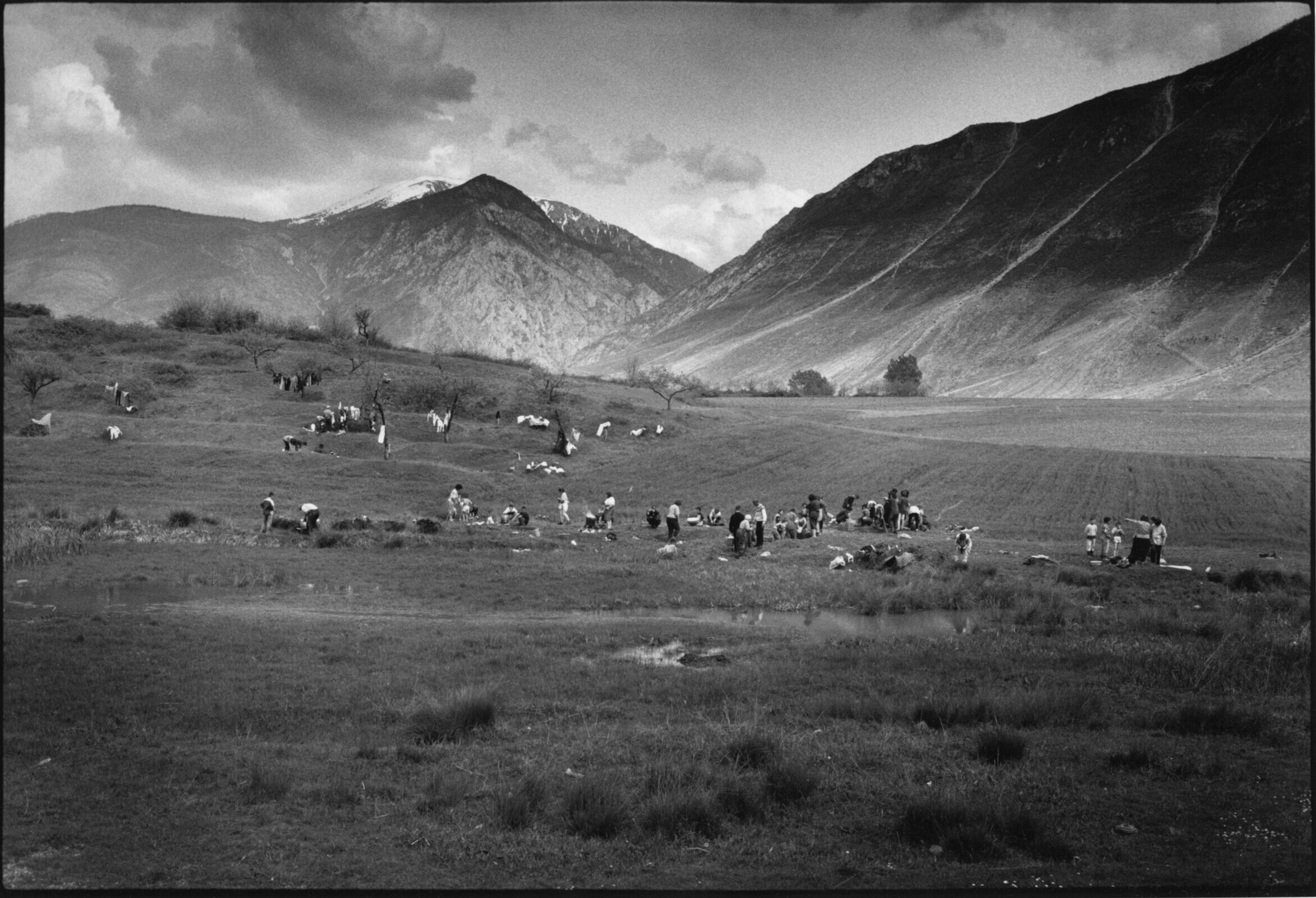

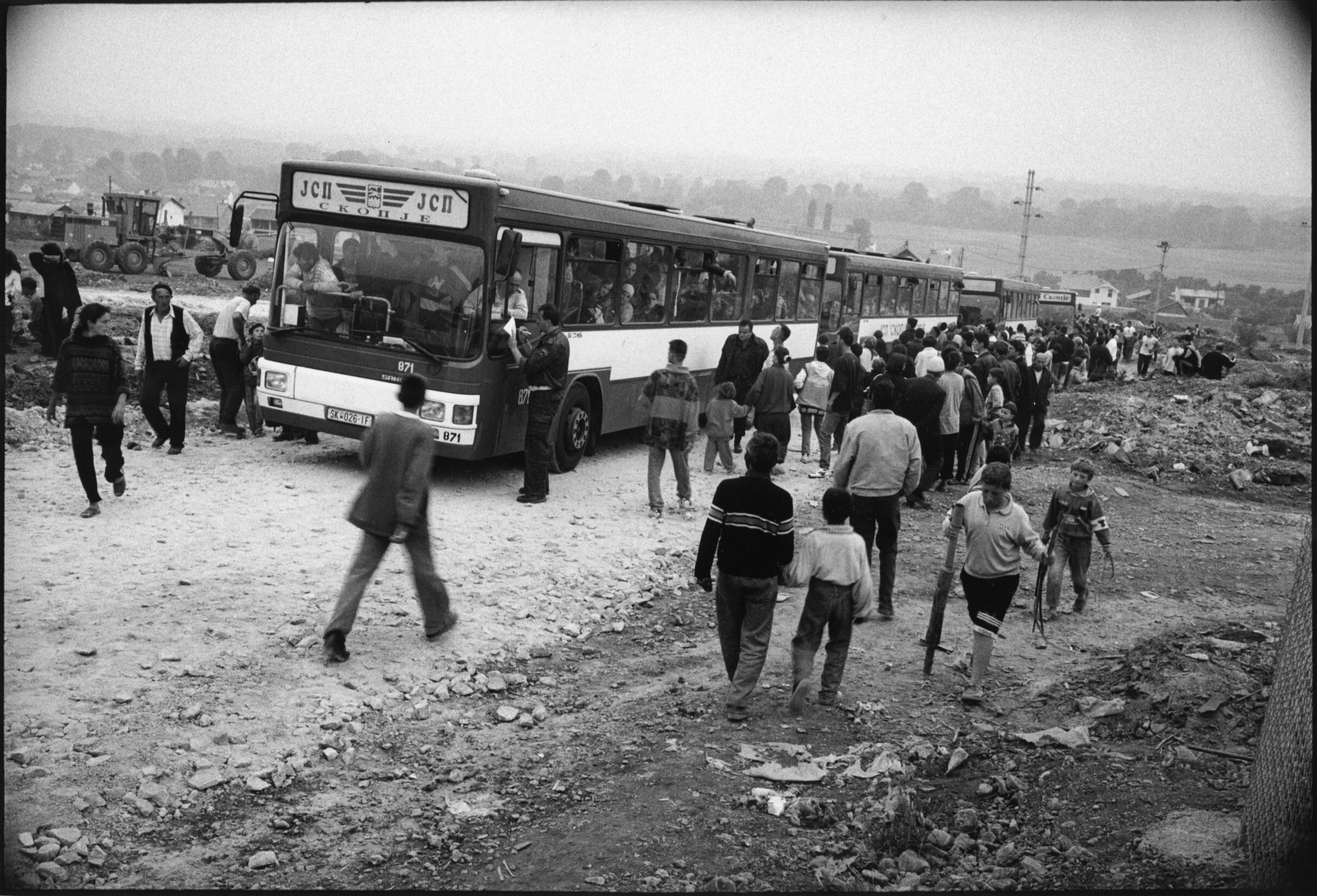

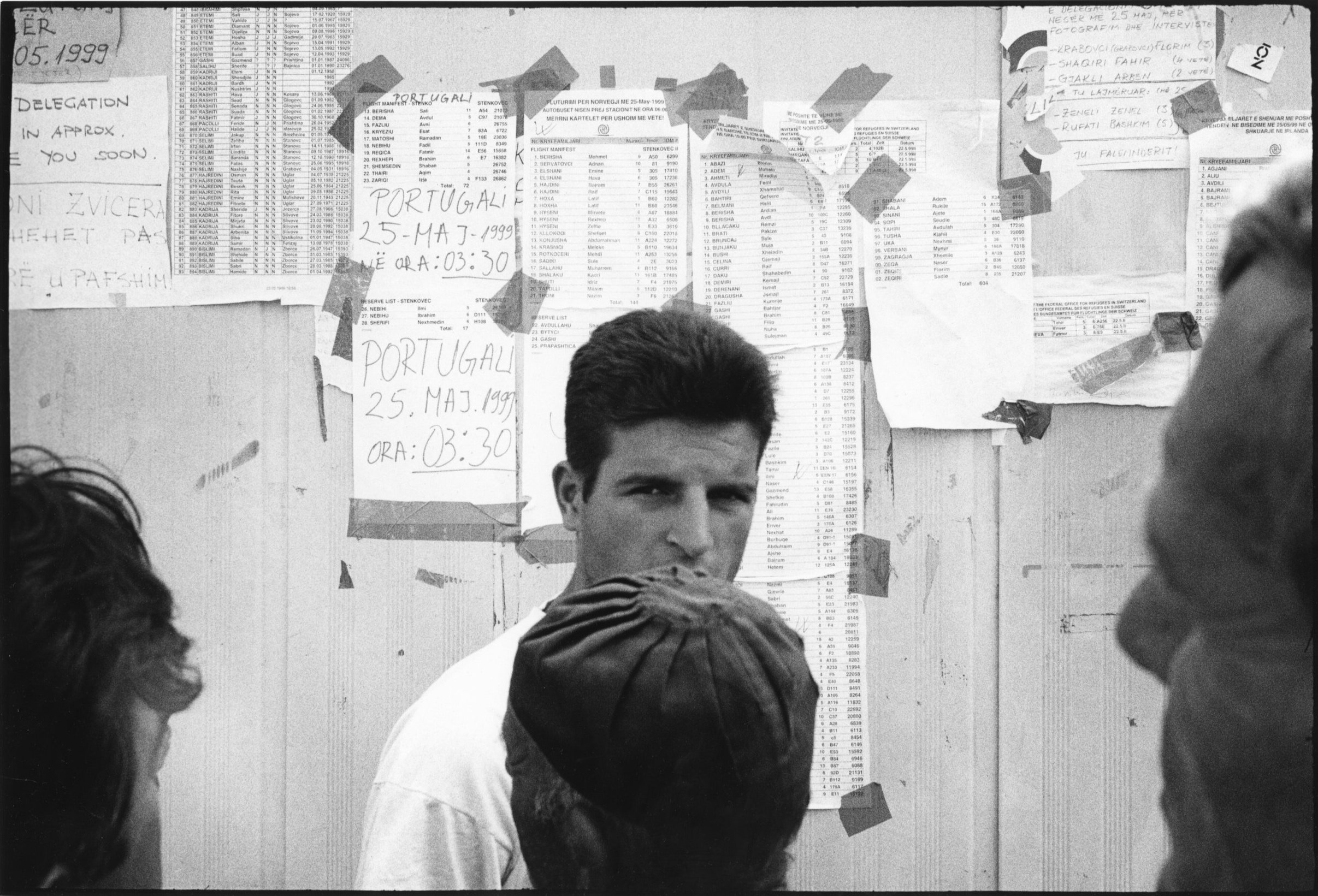

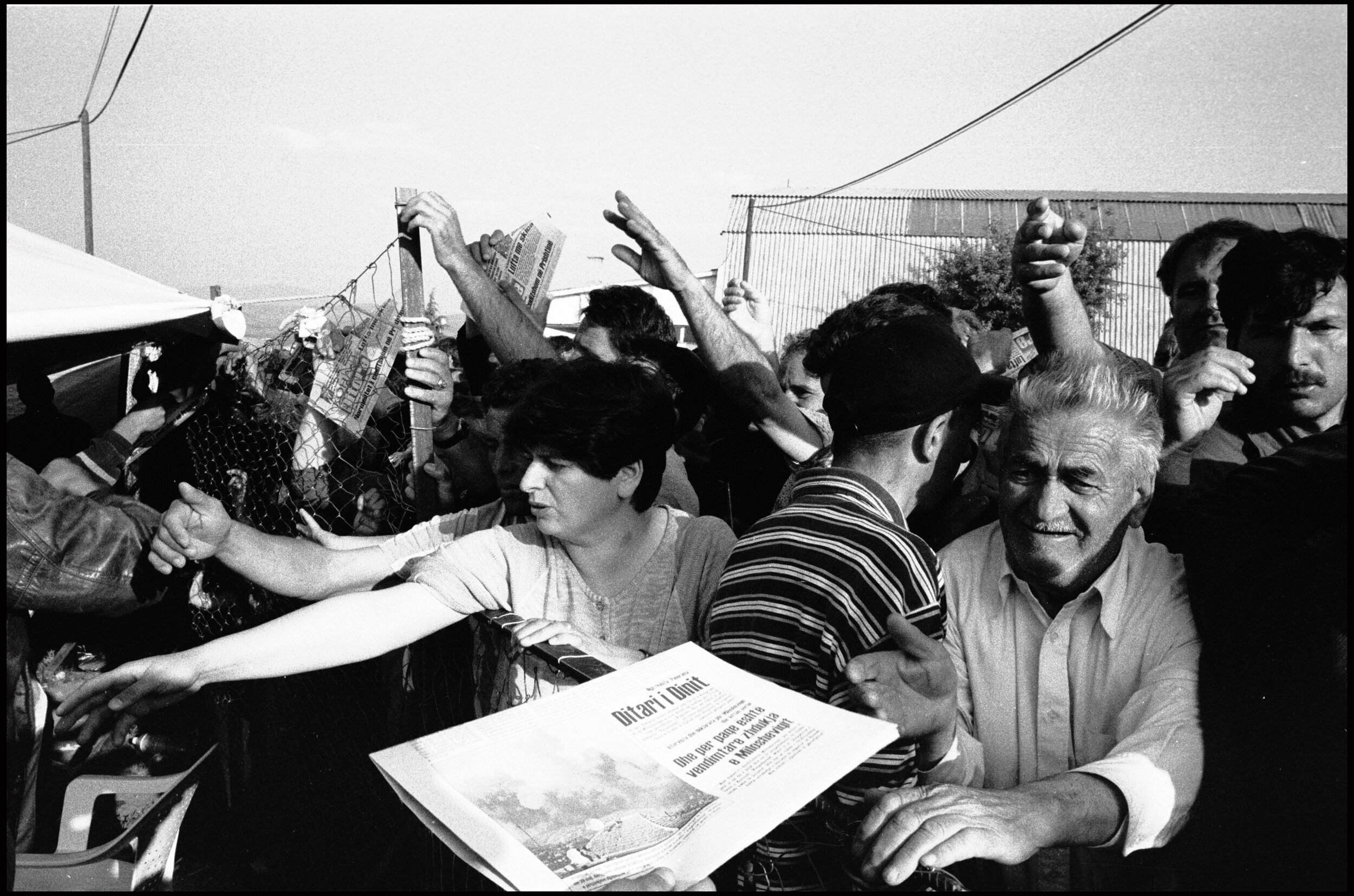

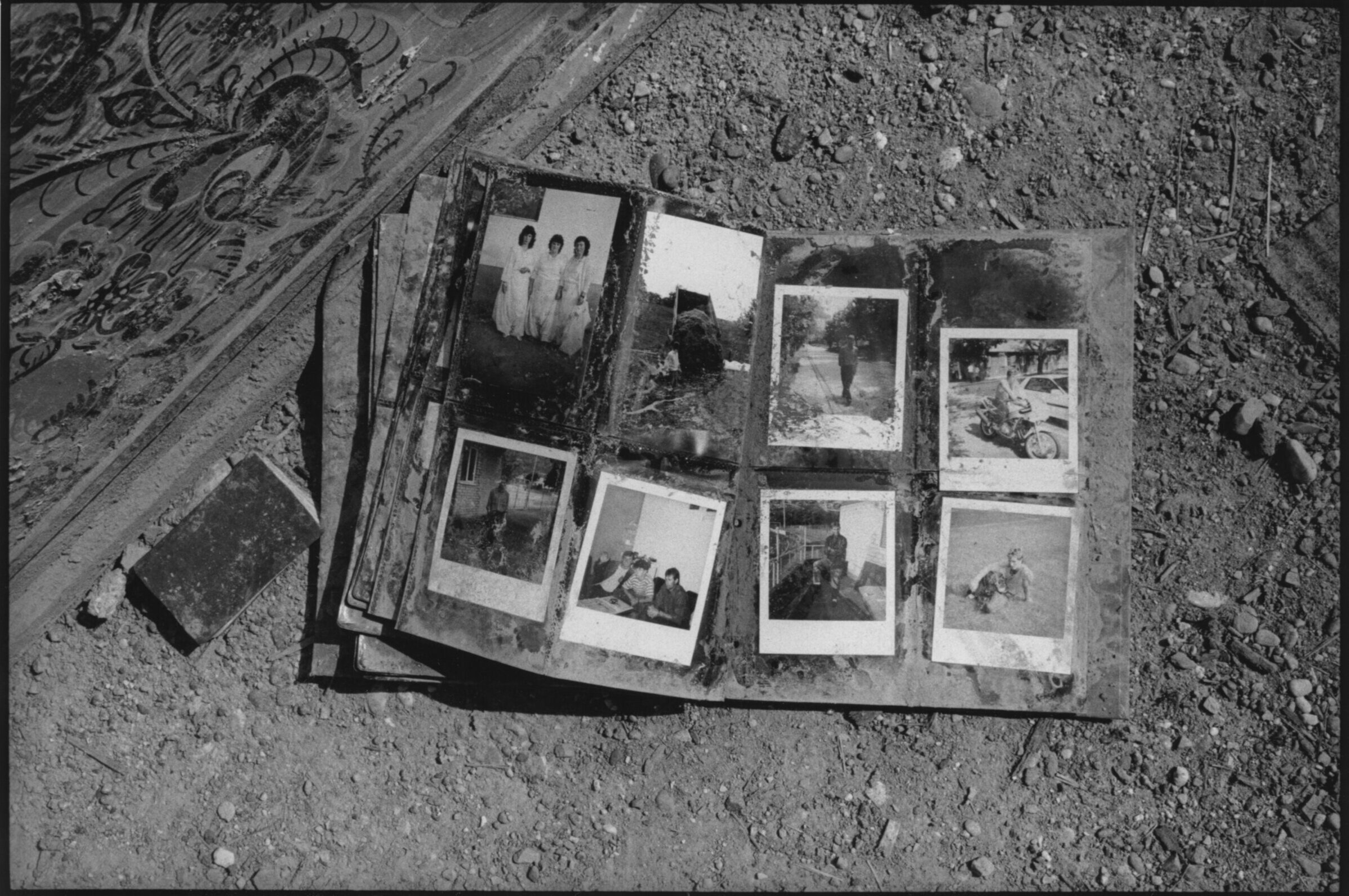

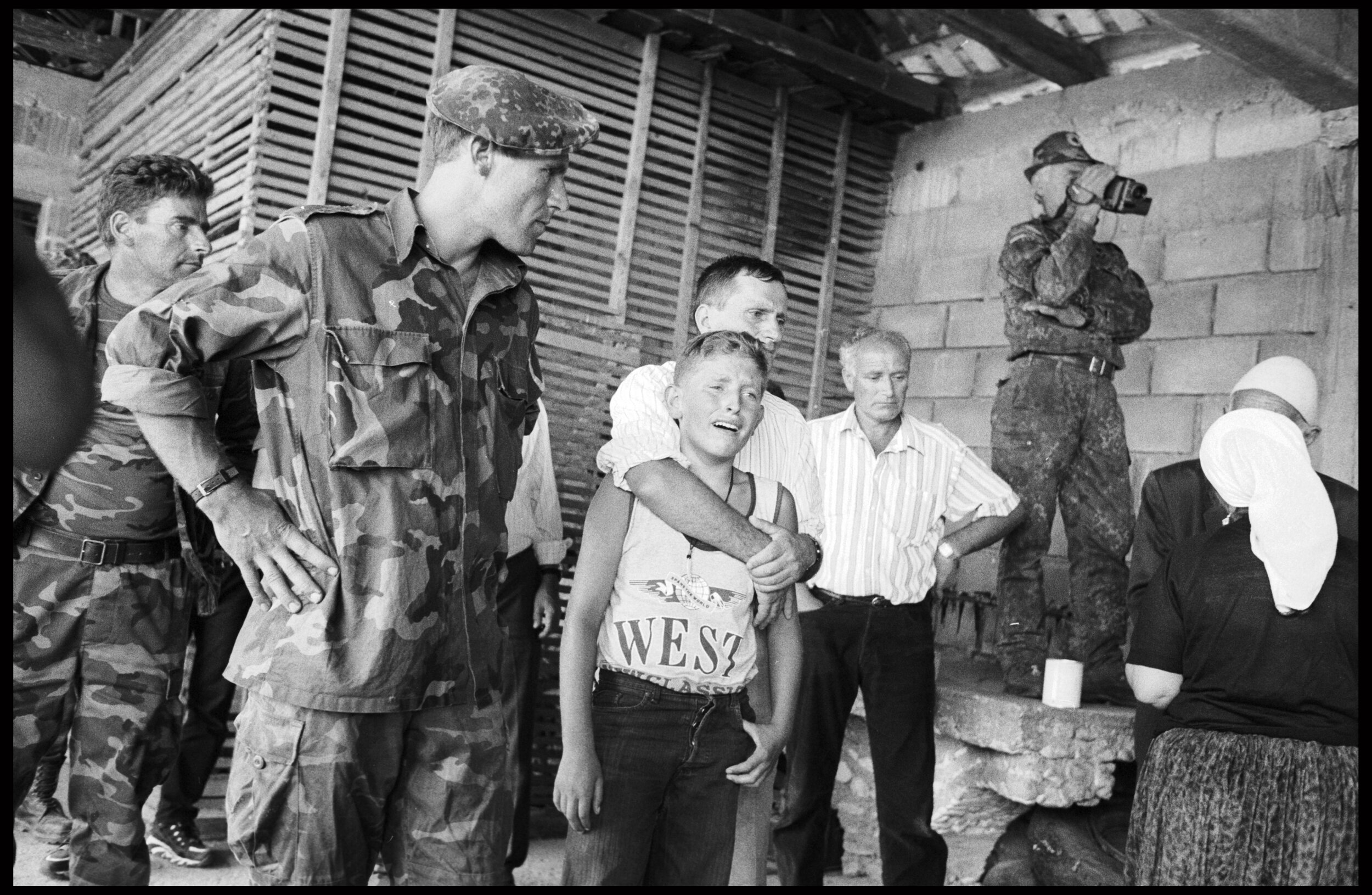

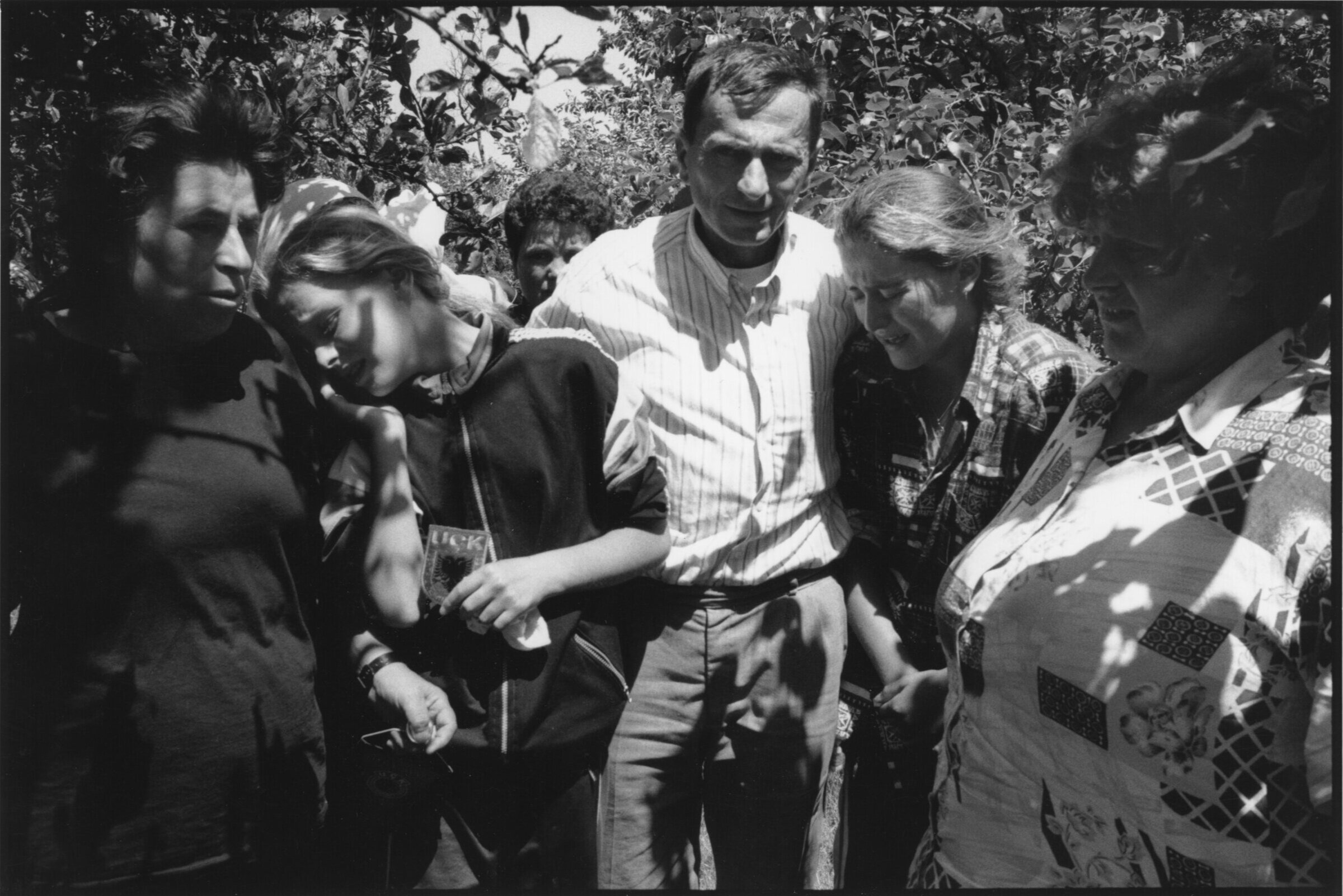

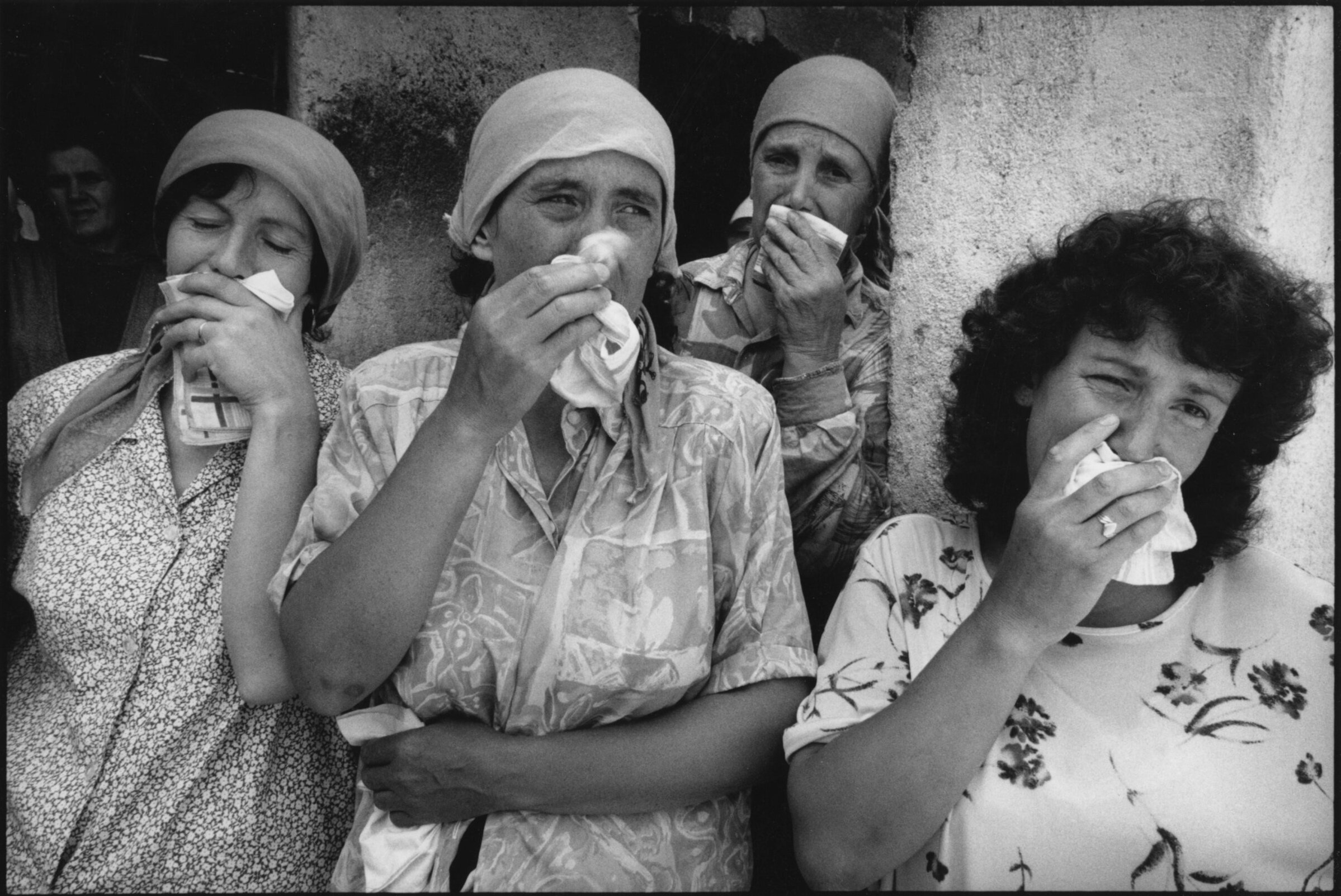

Deportation

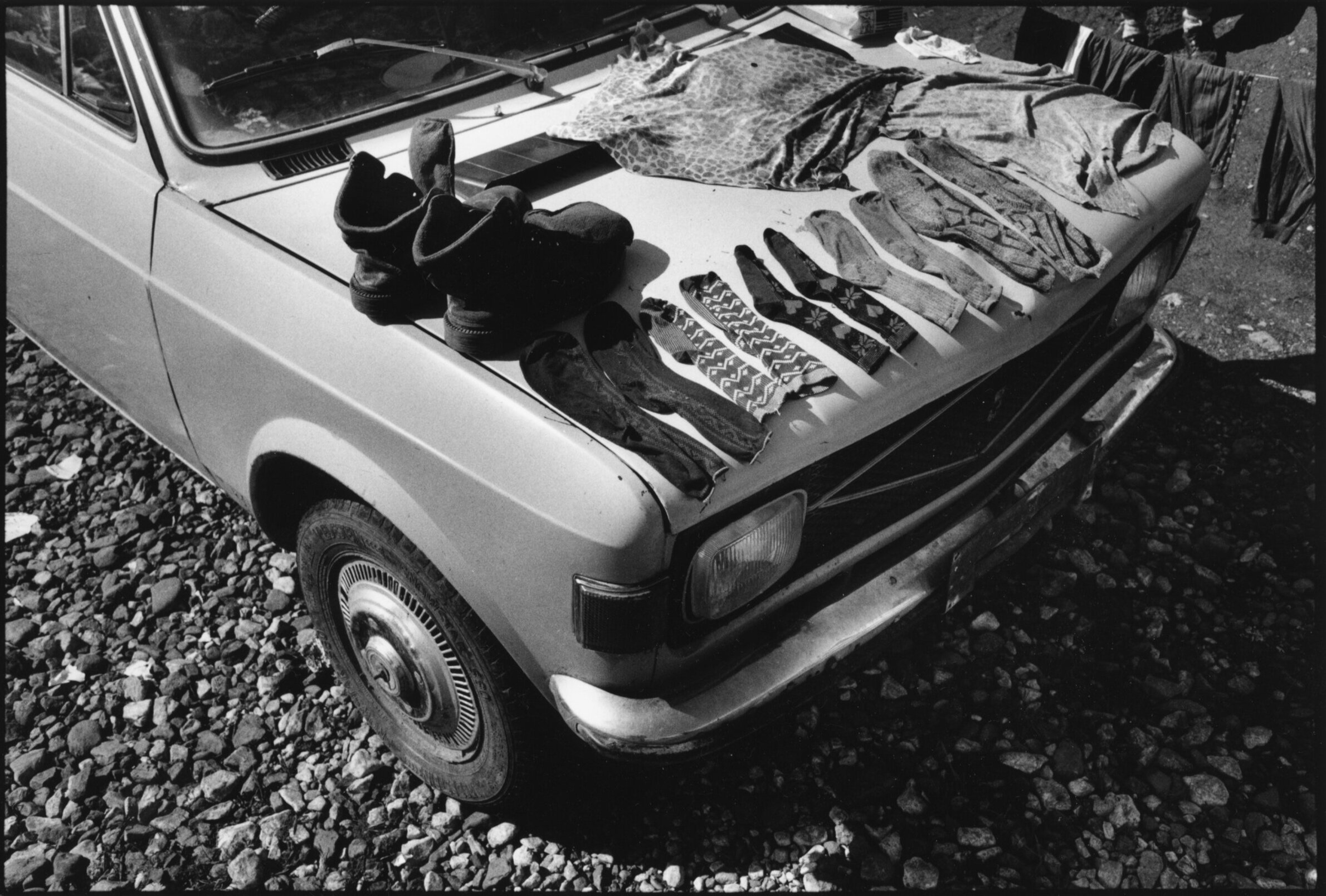

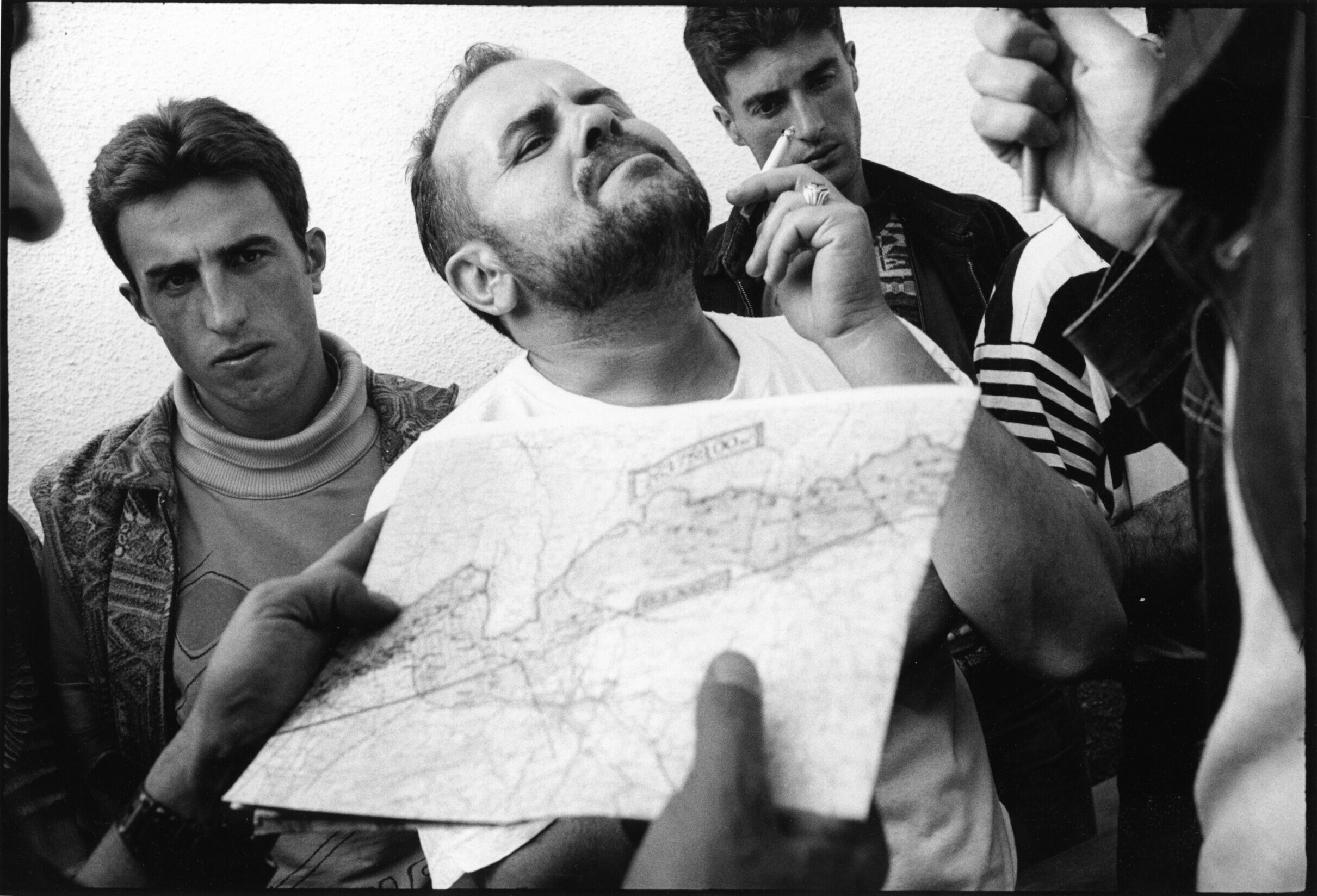

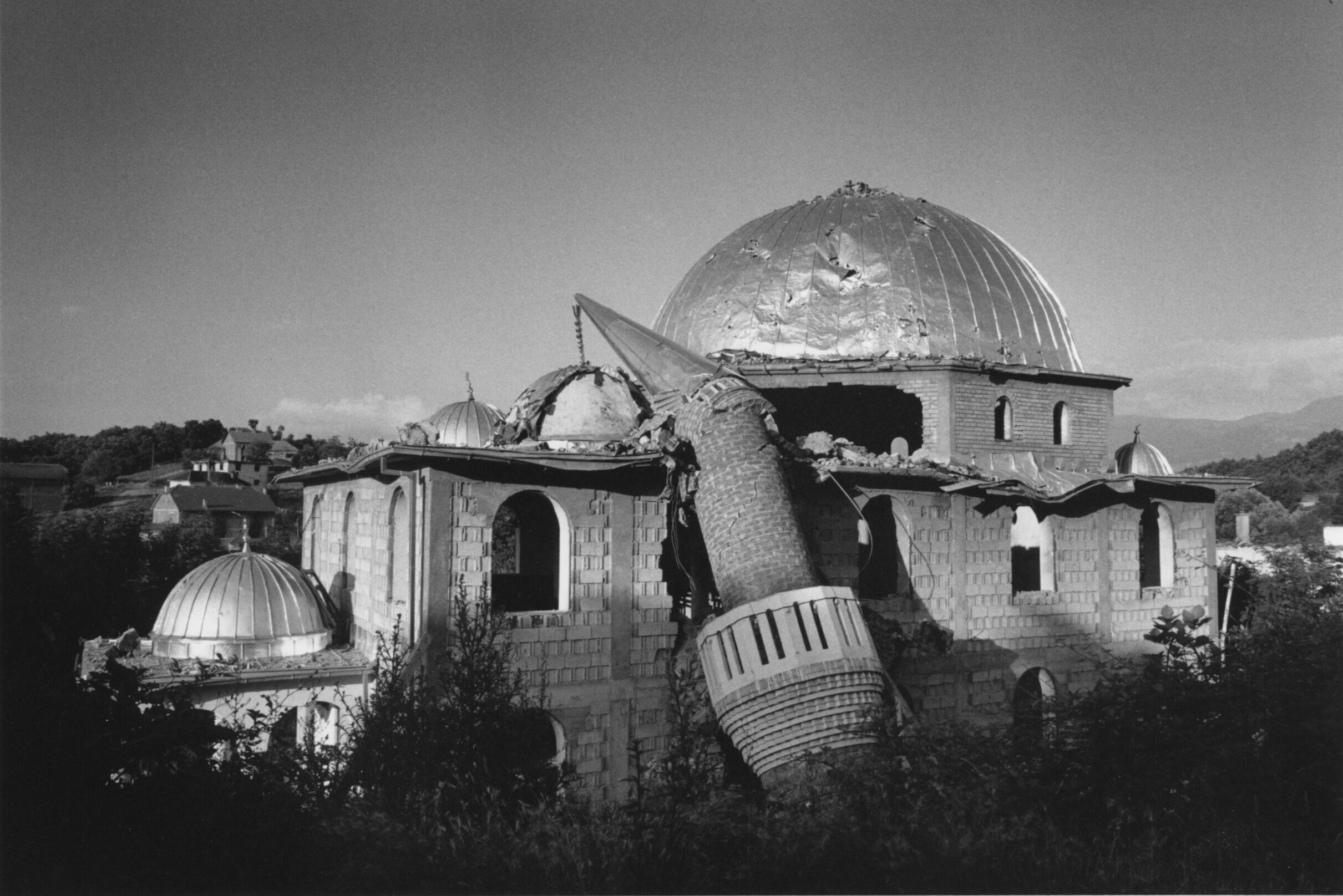

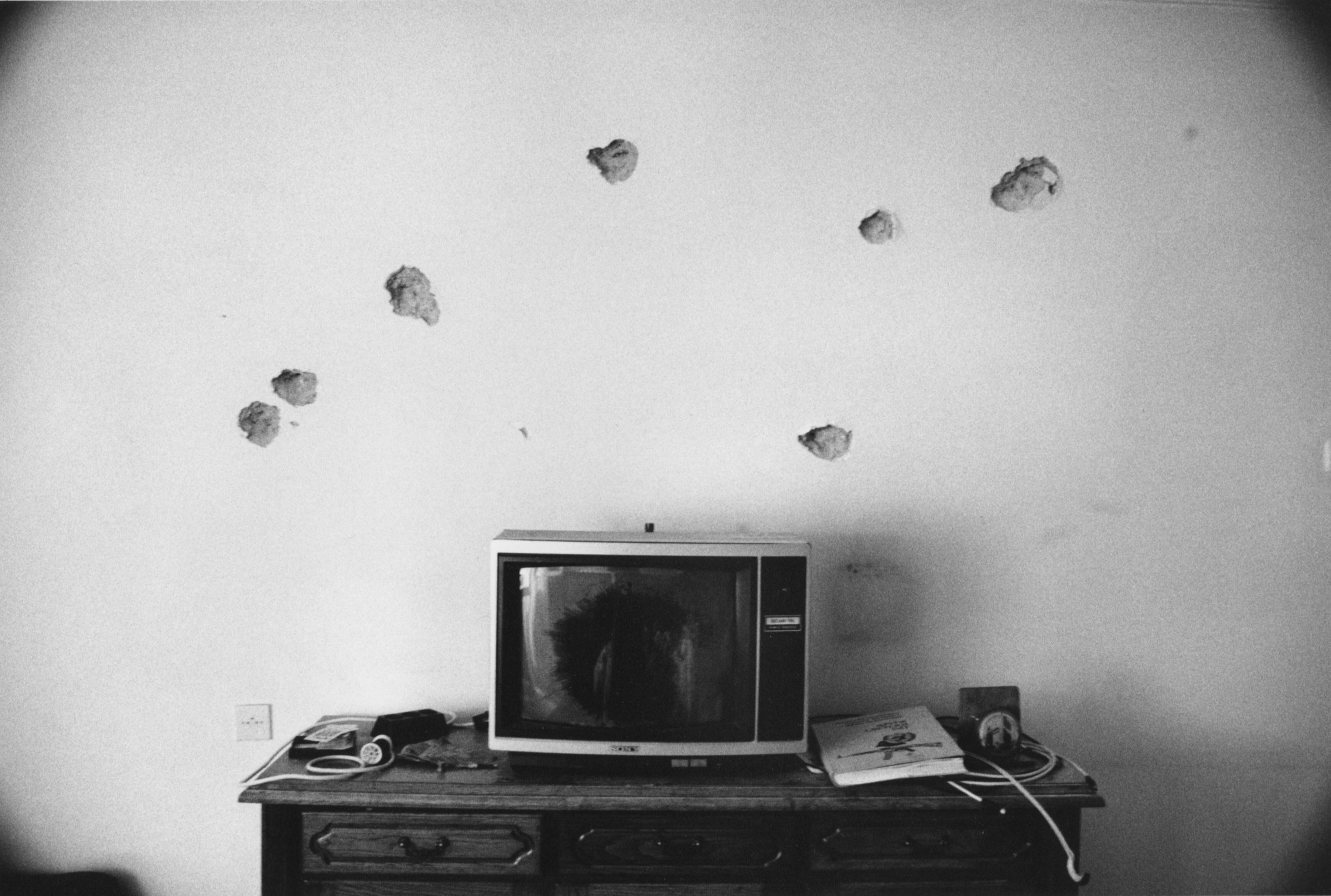

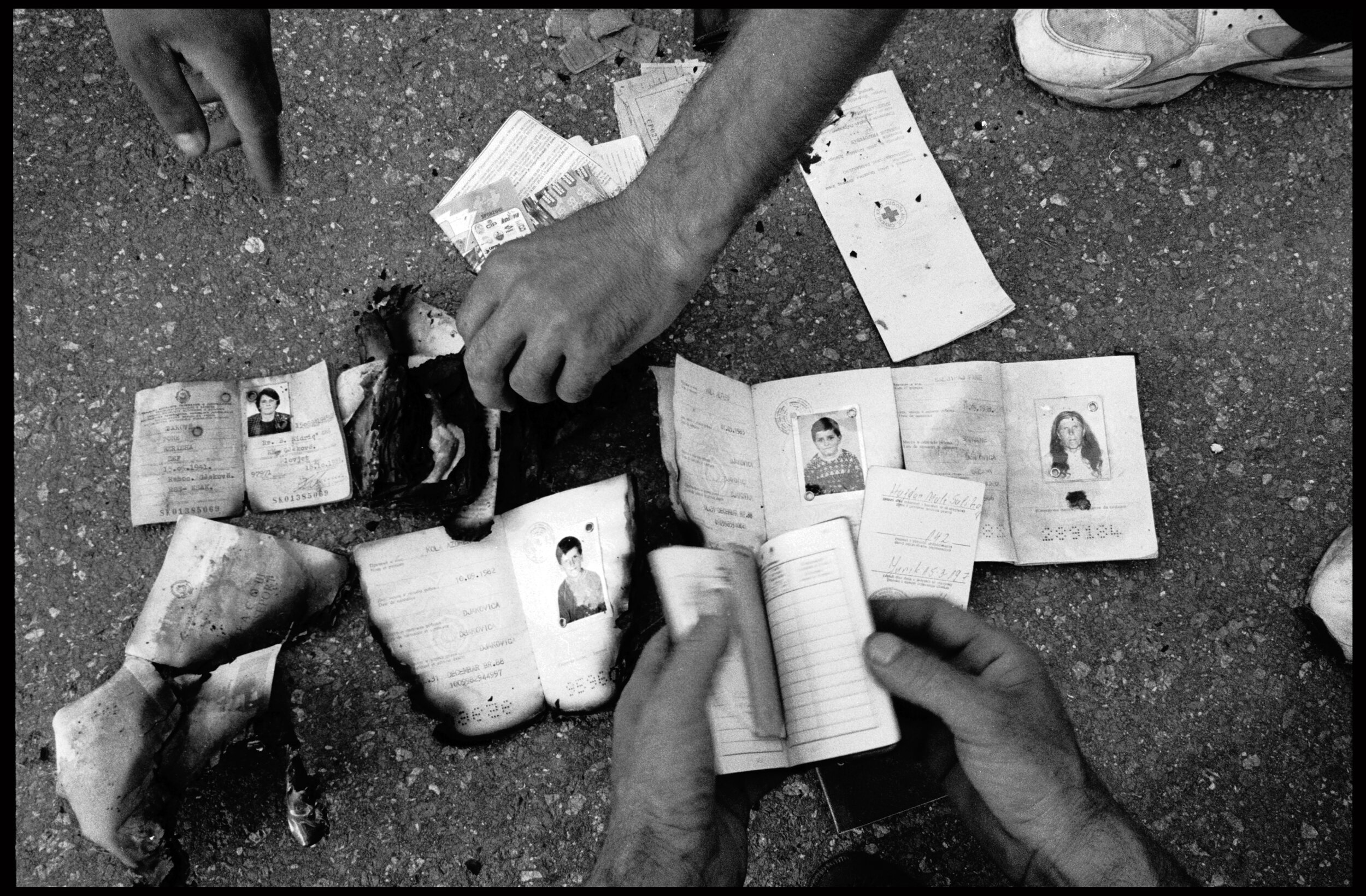

Persecution

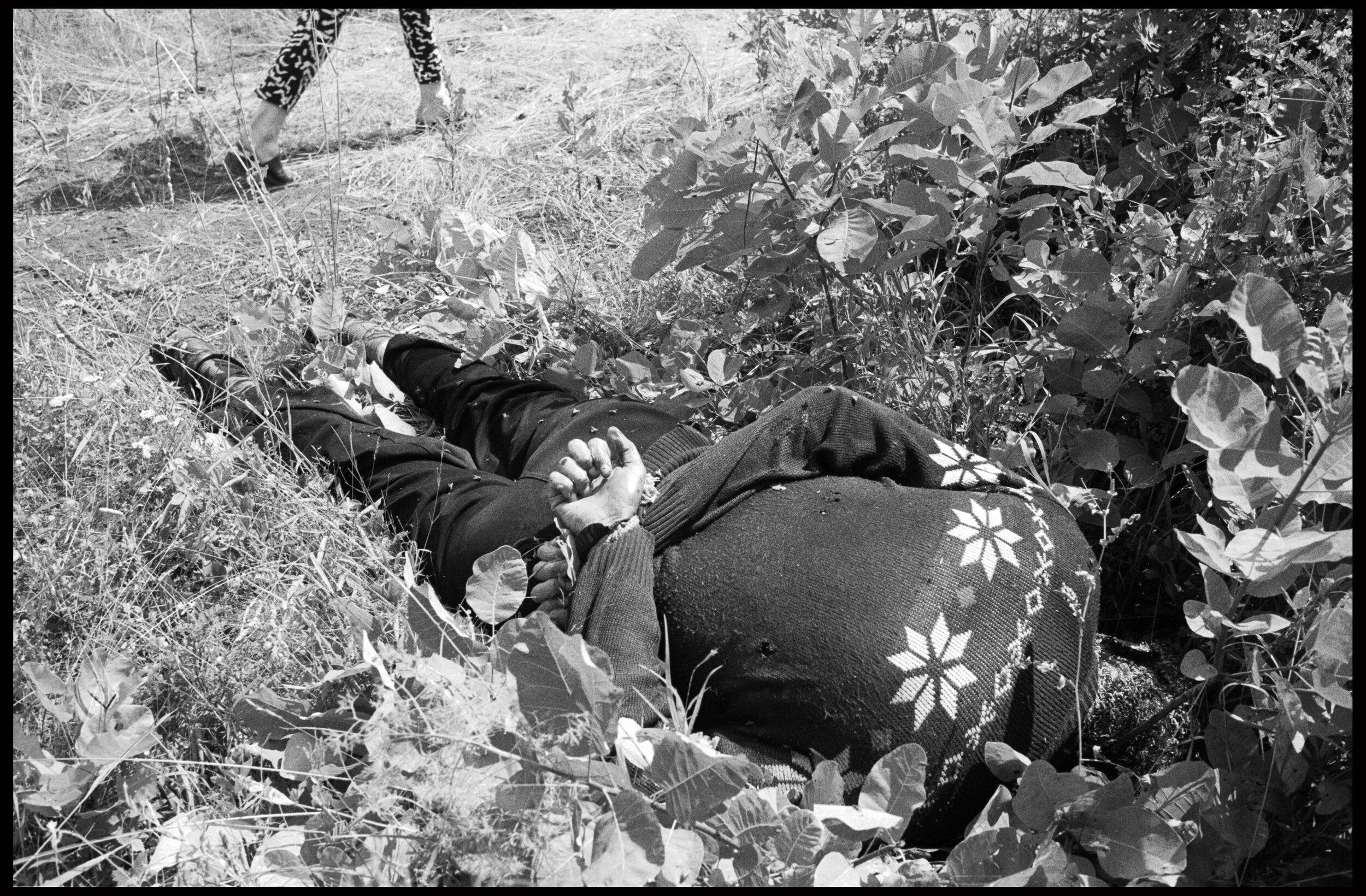

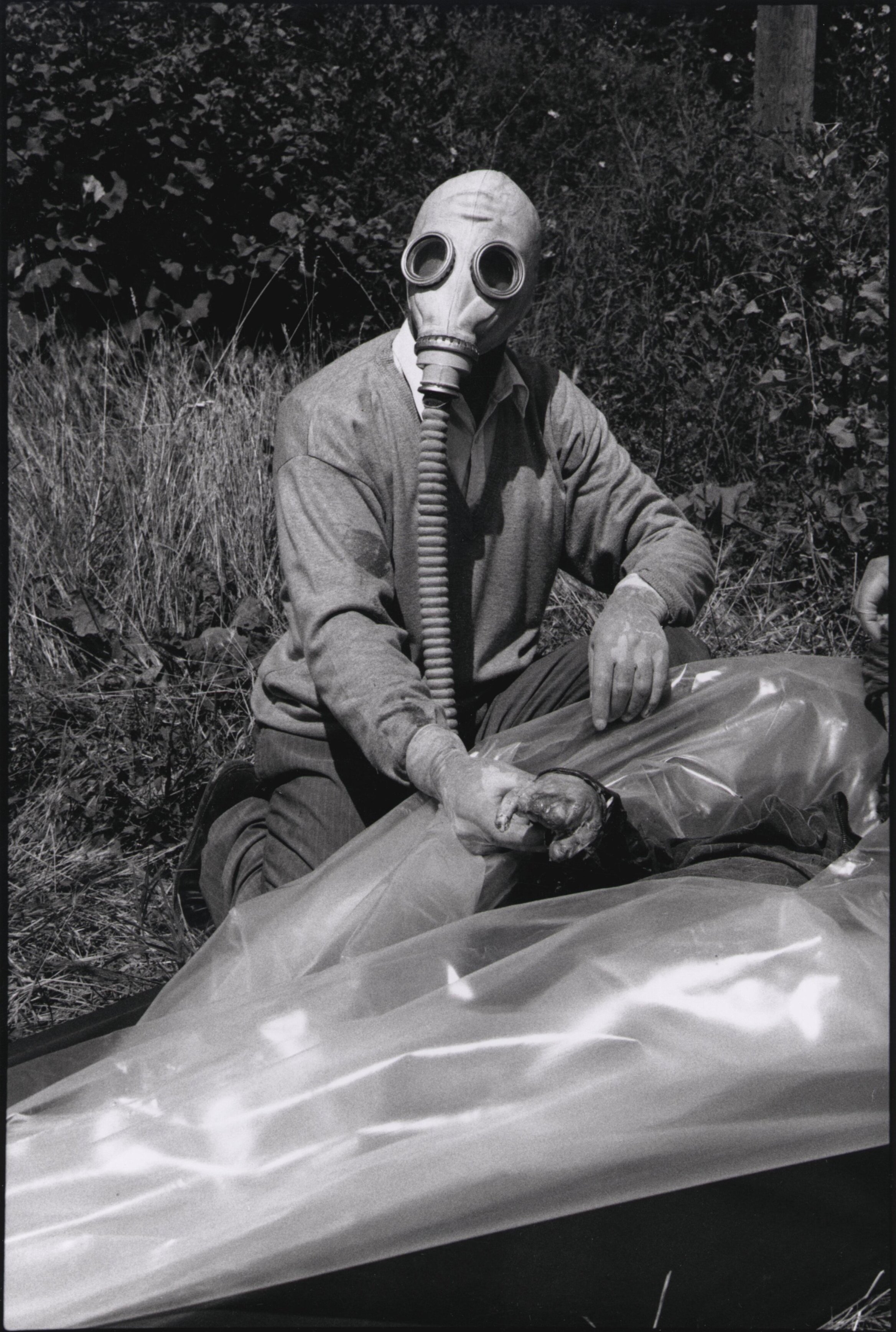

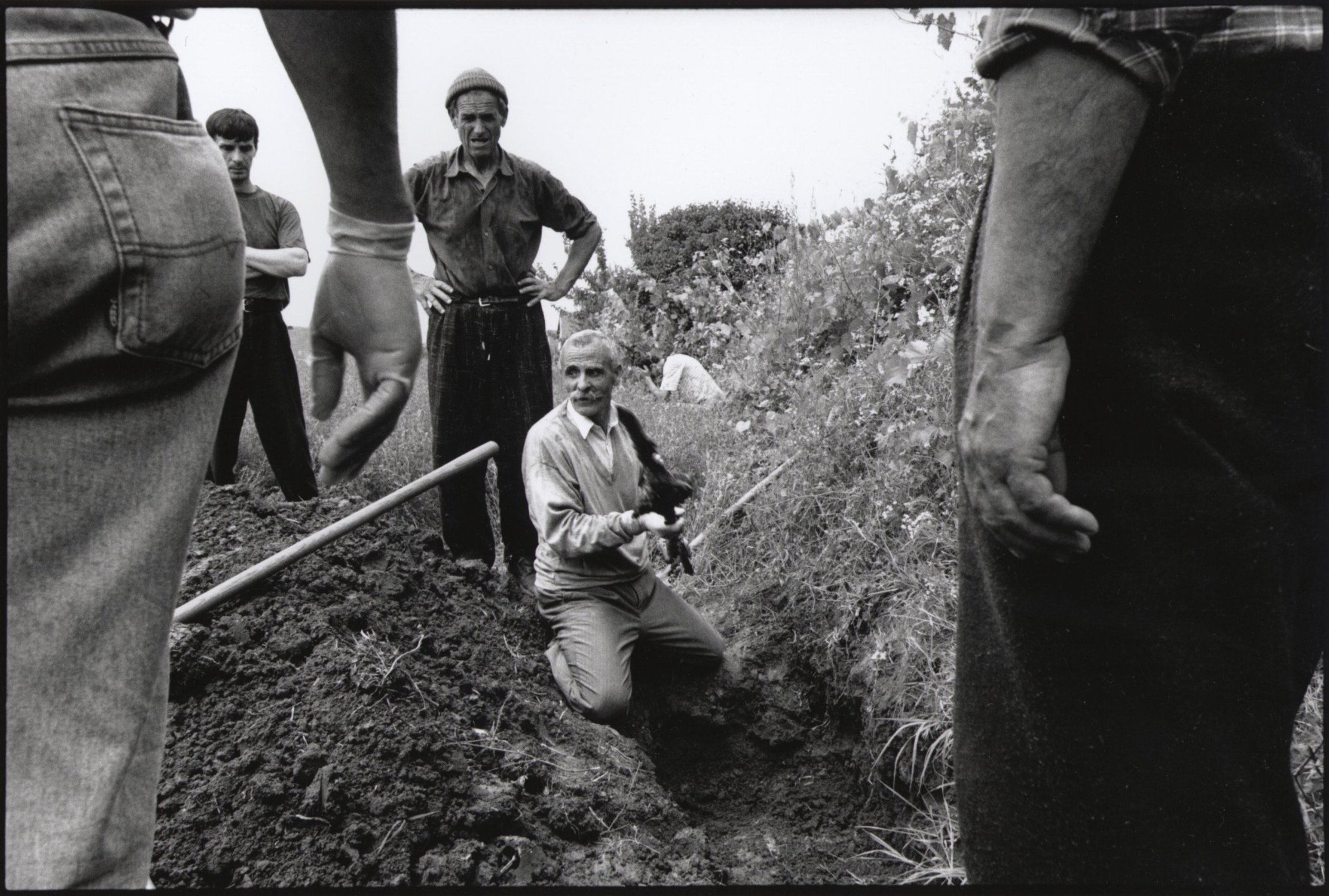

Murder

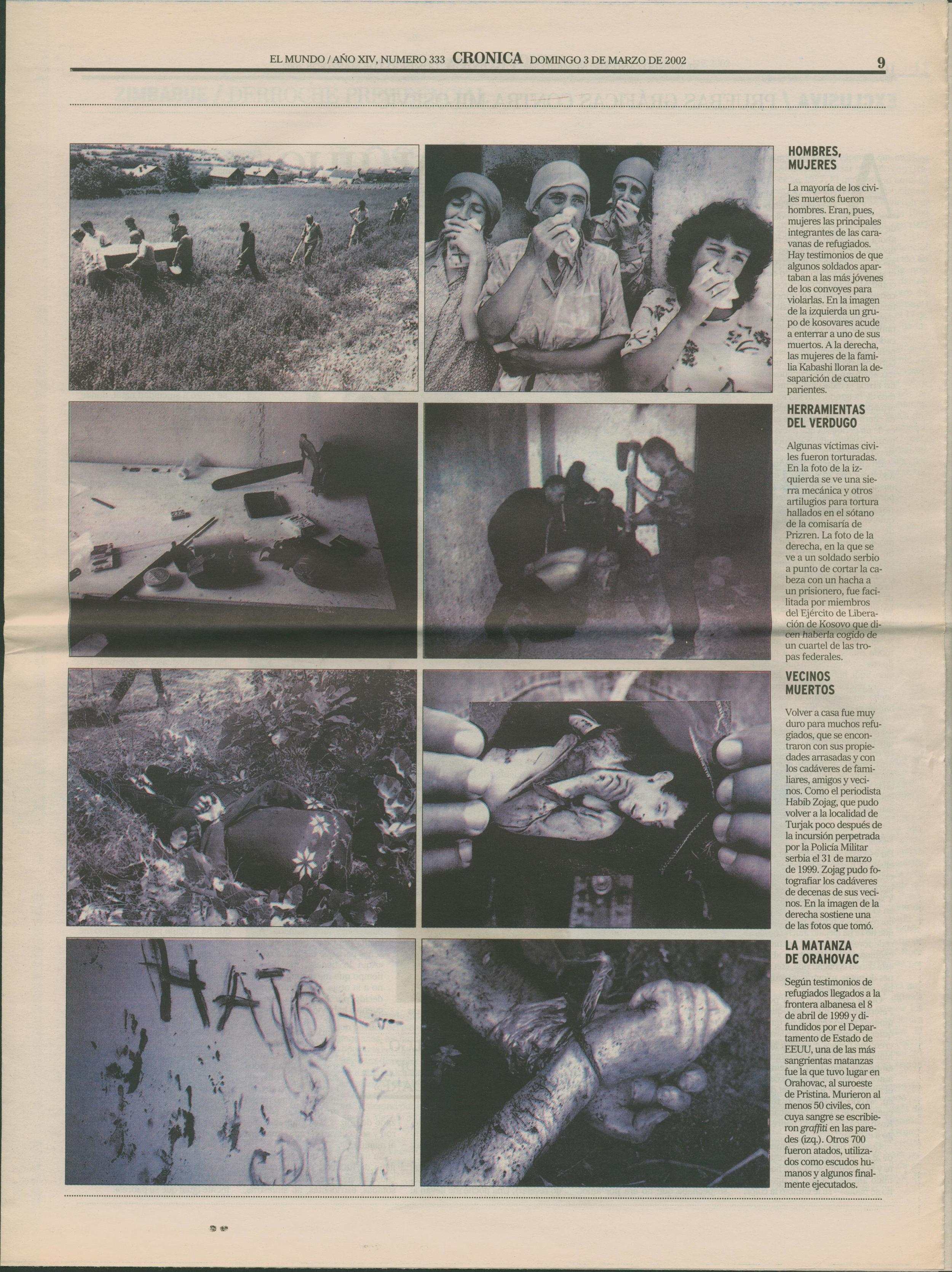

Publications

Rare limited edition copy of 'Evidence, The Case Against Milosevic' by Gary Knight & Anthony Loyd. deMo 2002.

+ Reading List

Evidence: The Case Against Milosevic. 2002, by Gary Knight and Anthony Loyd

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey through Yugoslavia. 1944, by Rebecca West

The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-2011. 2012, by Misha Glenny

The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War. 1996, by Misha Glenny

The Bridge over the Drina. 1994, by Ivo Andric

Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation. 1997, by Laura Silber and Allan Little

Kosovo: A Short History. 1999, by Noel Malcolm

Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U. S. Intervention. 2014, by David L Philips

Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2002, by Tim Judah

Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know. 2008, by Tim Judah

My War Gone By, I Miss It So. 2000, by Anthony Loyd

They Would Never Hurt a Fly: War Criminals on Trial in The Hague. 2004, by Slavenka Draculic

Eclats de Guerre. 2002, by Alexandra Boulat

Blood & Honey: A Balkan War Journal. 2001, by Ron Haviv

Ex Yougoslavie: 1991-1996. 1998, by Emmanuel Ortiz

Farewell to Bosnia. 1994, by Gilles Peress

The Silence. 1995, by Gilles Peress

Inferno. 1999, by James Nachtwey

Aftermath: Bosnia’s Long Road to Peace. 2005, by Sara Terry

Quest for Identity. 2012, by Ziyah Gafic

The Bone Woman: A Forensic Anthropologist’s Search for Truth in the Mass Graves of Rwanda, Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo. 2004, by Clea Koff