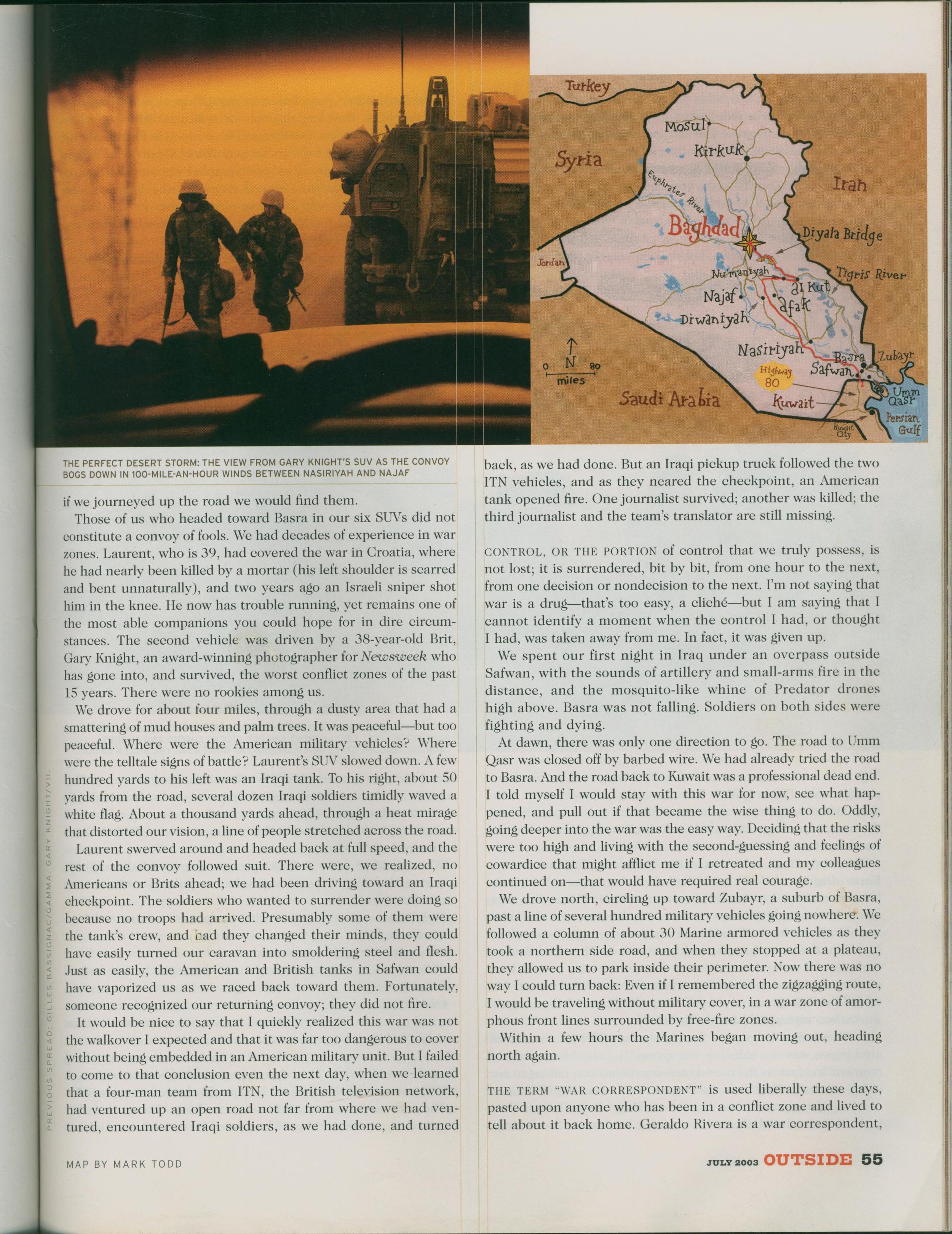

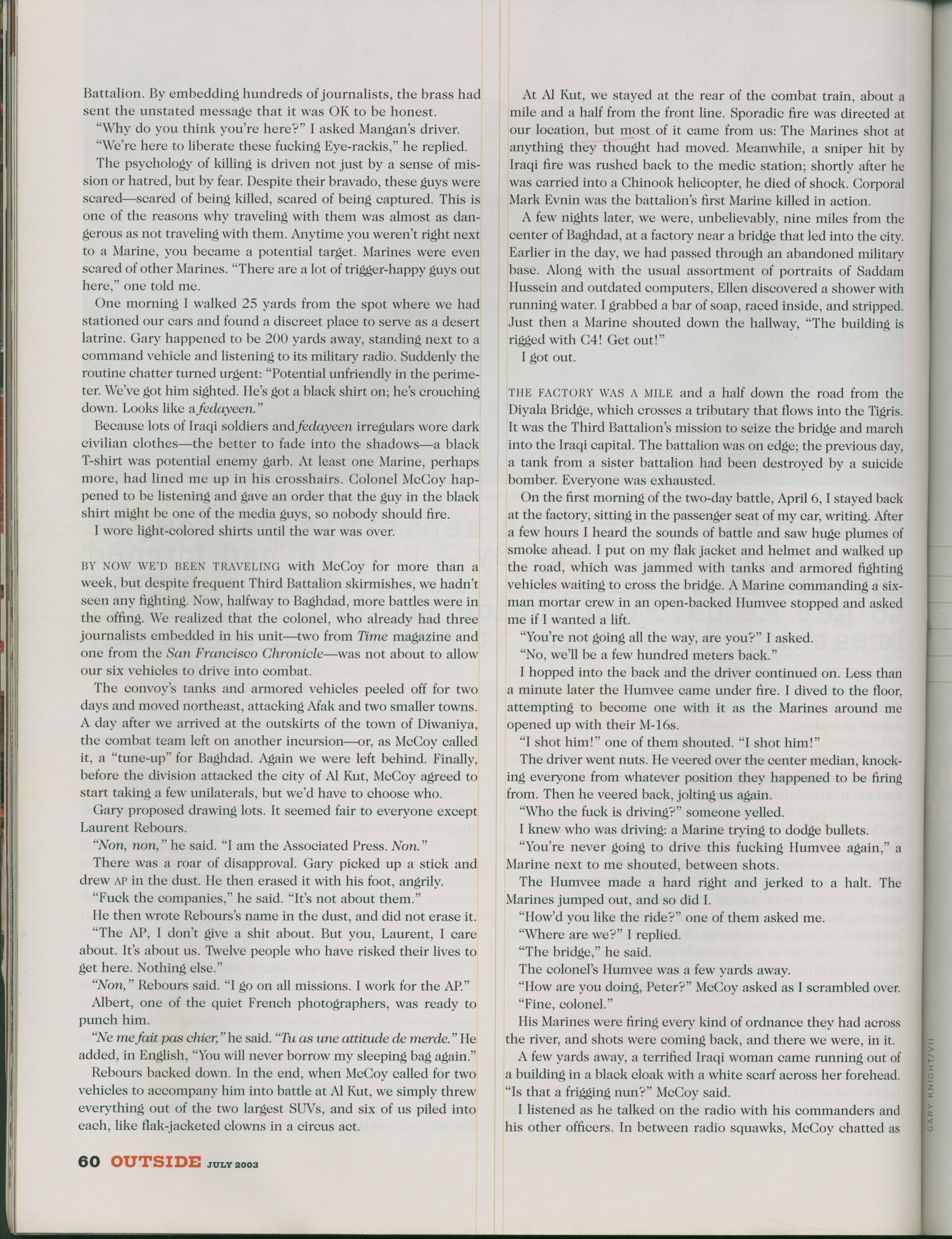

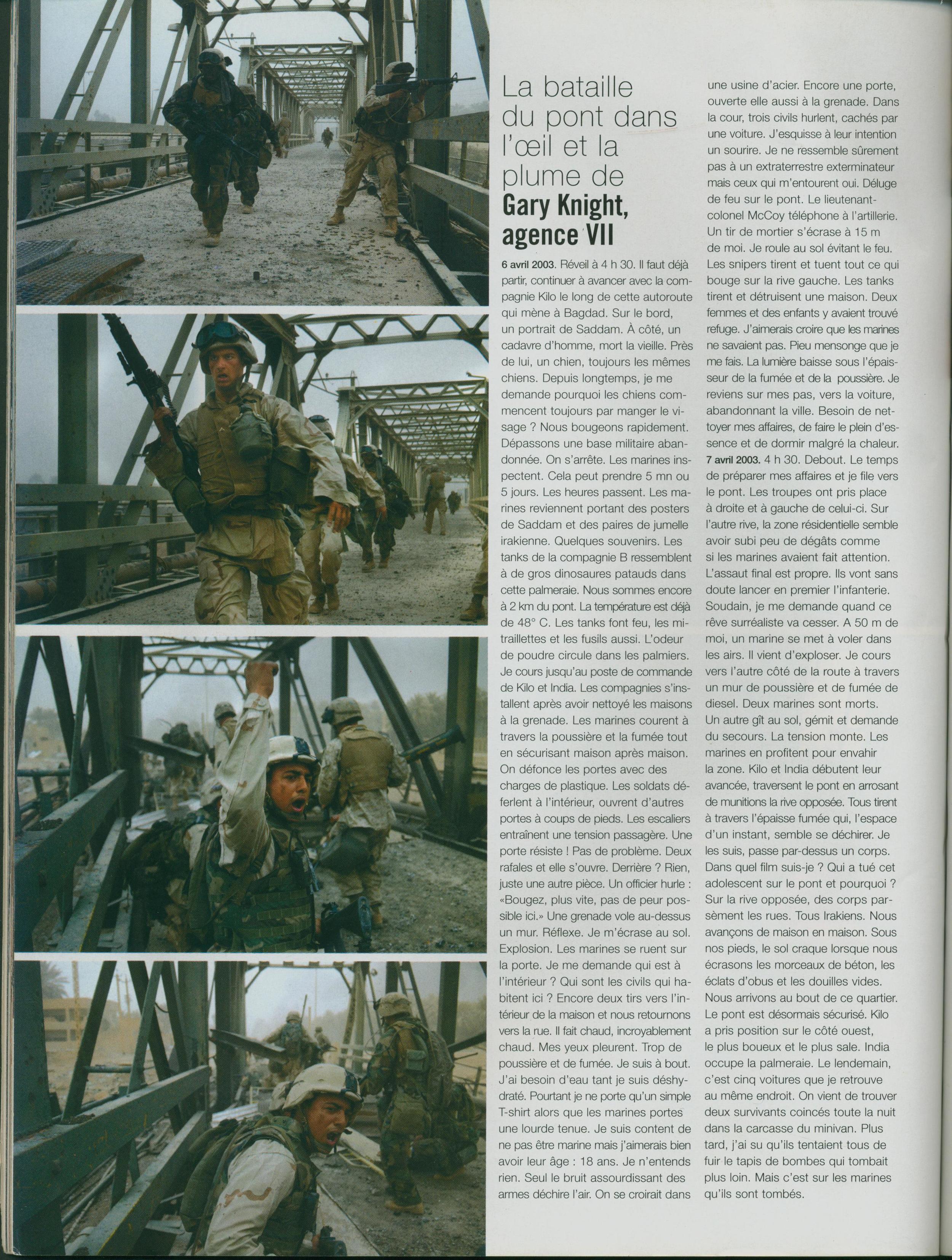

The 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines take Diyala Bridge during the battle for Baghdad. Photo: © Gary Knight

Invasion: The Battle for Dyala Bridge

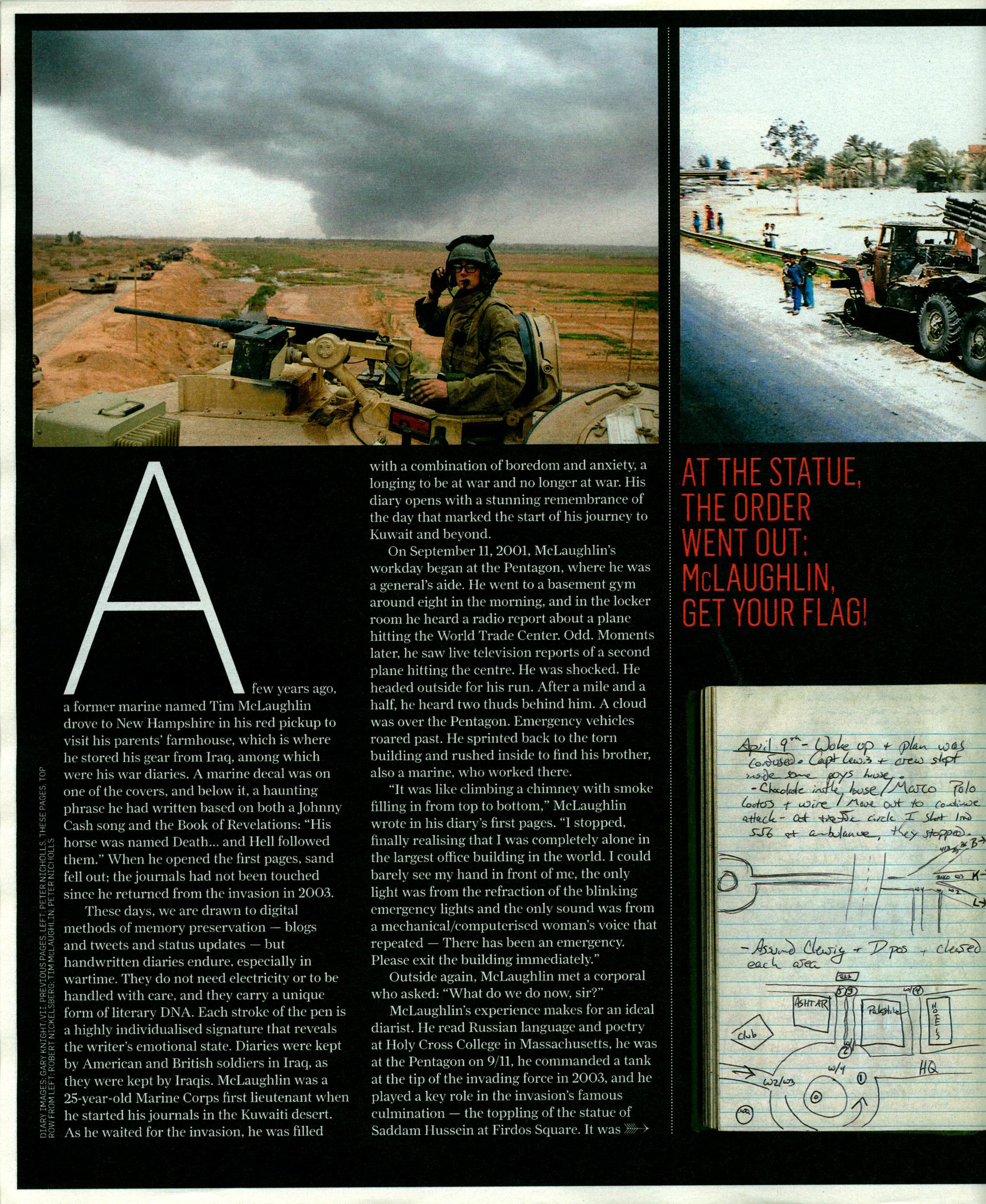

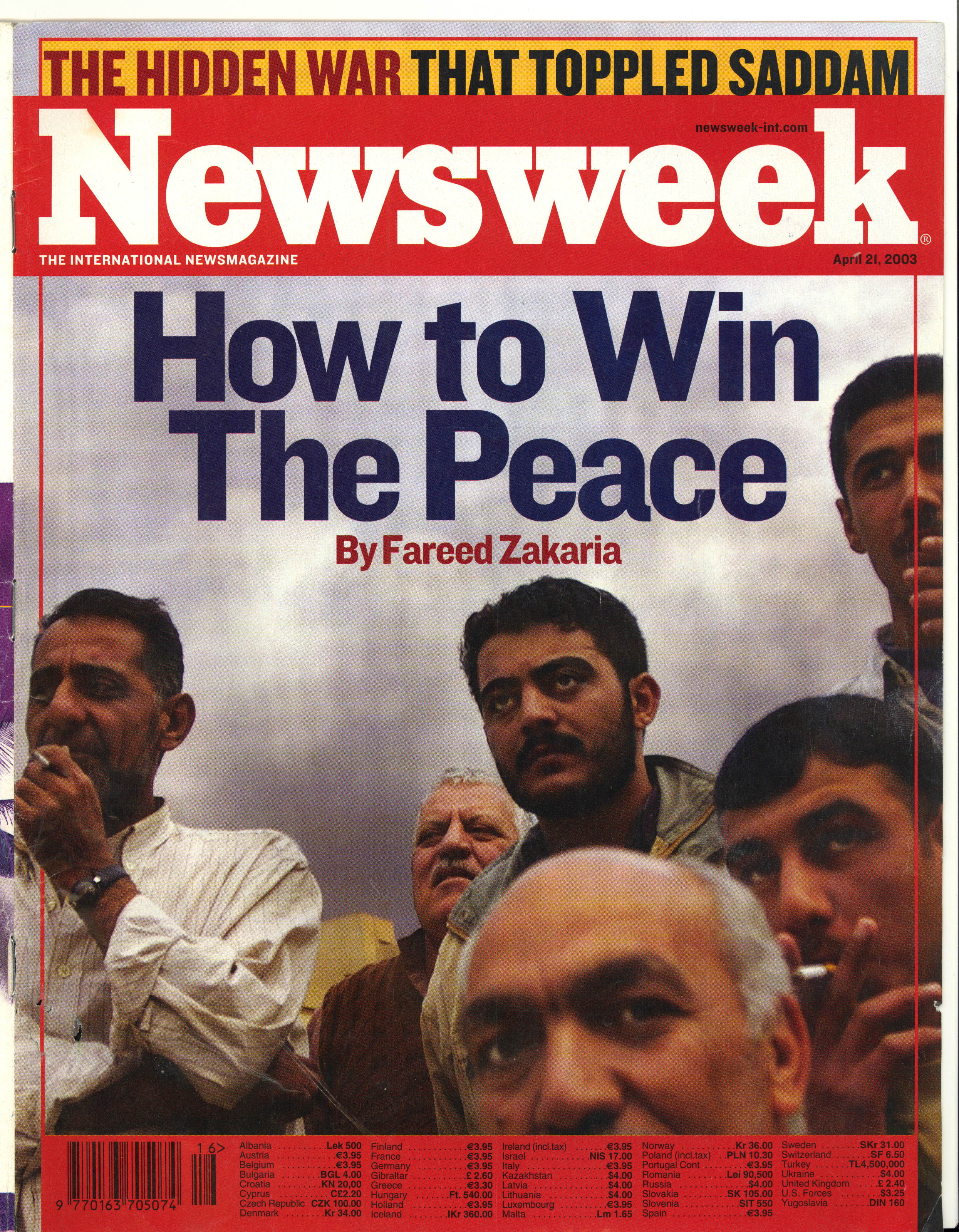

This project started as a straightforward news assignment to photograph the invasion of Iraq in 2003 for Newsweek. It has evolved into a remembered account of events witnessed by three men who processed them differently.

The project exists as an exhibition and eventually will become a book that includes my own journals of text and images; the journals of US Marine Lt. Tim McLaughlin, who commanded a tank in the battalion I followed into war; and the words of author and journalist Peter Maass, who was one in the small cadre of journalists with whom I made that journey.

In the winter of 2002-3—while Tim was deployed to the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines in their tented city a few kilometres east of the Sabriyah oil field in the Kuwaiti desert—approximately 2,000 journalists from all over the world were flying into Kuwait City and checking into air-conditioned luxury hotels to prepare to cover the looming US invasion of Iraq. Newsweek was assembling a large team of correspondents and photographers in Baghdad, Jordan, Kurdistan, and Kuwait. I had agreed with them that I would cover the war from an American perspective but that my coverage would focus on the effects of the war on the civilian population in the wake of the invasion forces. Kuwait was the obvious place to prepare for the invasion as the US had thousands of tanks and artillery stockpiled there from their first war in 1990.

I flew to Kuwait in January 2003 to join Rod Nordland and my Newsweek colleagues. I teamed up with a trusted and unorthodox friend from the Bosnian war, Italian photographer Enrico Dagnino, who became my travelling partner for the journey ahead. Newsweek rented me a four-wheel-drive Chevrolet Tahoe, and we supplied it with four spare wheels, eight jerry cans of gasoline and enough food, water, whisky, marijuana, and film to last about six weeks. We stockpiled maps, satellite communications equipment, tools, shovels, and camping gear. Chris Morris had sourced me some equipment that transmitted signals on NATO frequencies so that my vehicle would be identified as “friendly” to NATO aircraft and armoured vehicles. Once prepared, we waited with a small group of journalists to cross the border into Iraq as soon as the invasion started.

There were two options for covering the invasion that were given to the press corps. One was to be embedded in a military unit, meaning you would have the logistical advantage of being driven to the war, fed, watered, and taken care of by them but the disadvantage of no flexibility about which part of the war you would see, if any. (In the first Gulf War, embedded journalists saw almost nothing.) The other option, according to the US military press office, was to be escorted over the border after the invasion started in busses and convoys under military escort to see the war. Precedent and common sense suggested that trusting the press office to stick to its word would end in tears, and the embedding process seemed to be a gamble with poor odds. My assignment and personality demanded more liberty. With a small group of colleagues, mostly freelance photographers, I chose to go my own way. The military seemed to think none of us would make this choice. We calculated that the chances of censure and punishment, as well as the security risk, were high, but such is the nature of covering a war. Less than twenty of us made that choice, and as it turned out, we got closer to the violence than all but a small number of embedded journalists. The folks who waited in Kuwait got nowhere.

I drove out to the border from Kuwait City every day to see how the landscape was evolving, as the theatrics in Washington and at the UN suggested war was inevitable and close. The US military weren't going to tell us when the war would start, but it was easy to identify the signs in the landscape. The intentions of giant armies are hard to disguise, and we knew what we were looking for. Roads were discreetly being closed, barriers and checkpoints were being erected at night, everyone but essential workers was being moved away from the border, and there was more evidence of US and British military police moving on the roads.

Three days before the invasion, I moved to a farm on the border where my Newsweek colleagues Luc Delahaye and Scott Johnson were hiding to wait for the war to come to us. It was clear the entire area was about to be sealed off. Enrico and I had covered the Chevy in oil and sand; we were dressed in a melange of British and Italian military uniforms and civilian clothing. We had NATO insignia on the roof and doors of the vehicle and were prepared to bluff our way across the border with invading forces.

Two days later, British Special Forces blew up an Iraqi ammo dump, and the border bloomed with artillery and airstrikes.

We drove up and down the border to all the crossings in the sector, trying to break through into Iraq from dawn until early afternoon. With every hour that passed, the possibility of getting caught by the Military Police increased. During this frustrating stretch of time, Enrico and I came across a few other vehicles with about a dozen other journalists who were trying to do the same thing we were.

At some point, knowing the chances of crossing were diminishing with every hour, we made the decision to drive to the Safwan border crossing, the main peacetime land border where Route 80 crosses into Iraq, and take our chances there with the Kuwaiti Army. When we pulled up to the barrier, a young soldier approached the Chevy and asked me who we were and what we were doing. I told him we were “Civil Affairs”—we stared at each other, both knowing I was bullshitting him. Enrico and I didn’t look quite right, and the soldier asked me to wait while he went to find a senior officer. I knew if an officer came, he would turn us around or arrest us immediately and that would be the end of the war before we had even started. Instead, I put my foot down on the gas and smashed through the barrier, my colleagues following behind us. I reasoned the Kuwaitis wouldn’t shoot us, because they didn’t know who we were, and they were unlikely to chase us into Iraq.

Our part in the invasion was on.

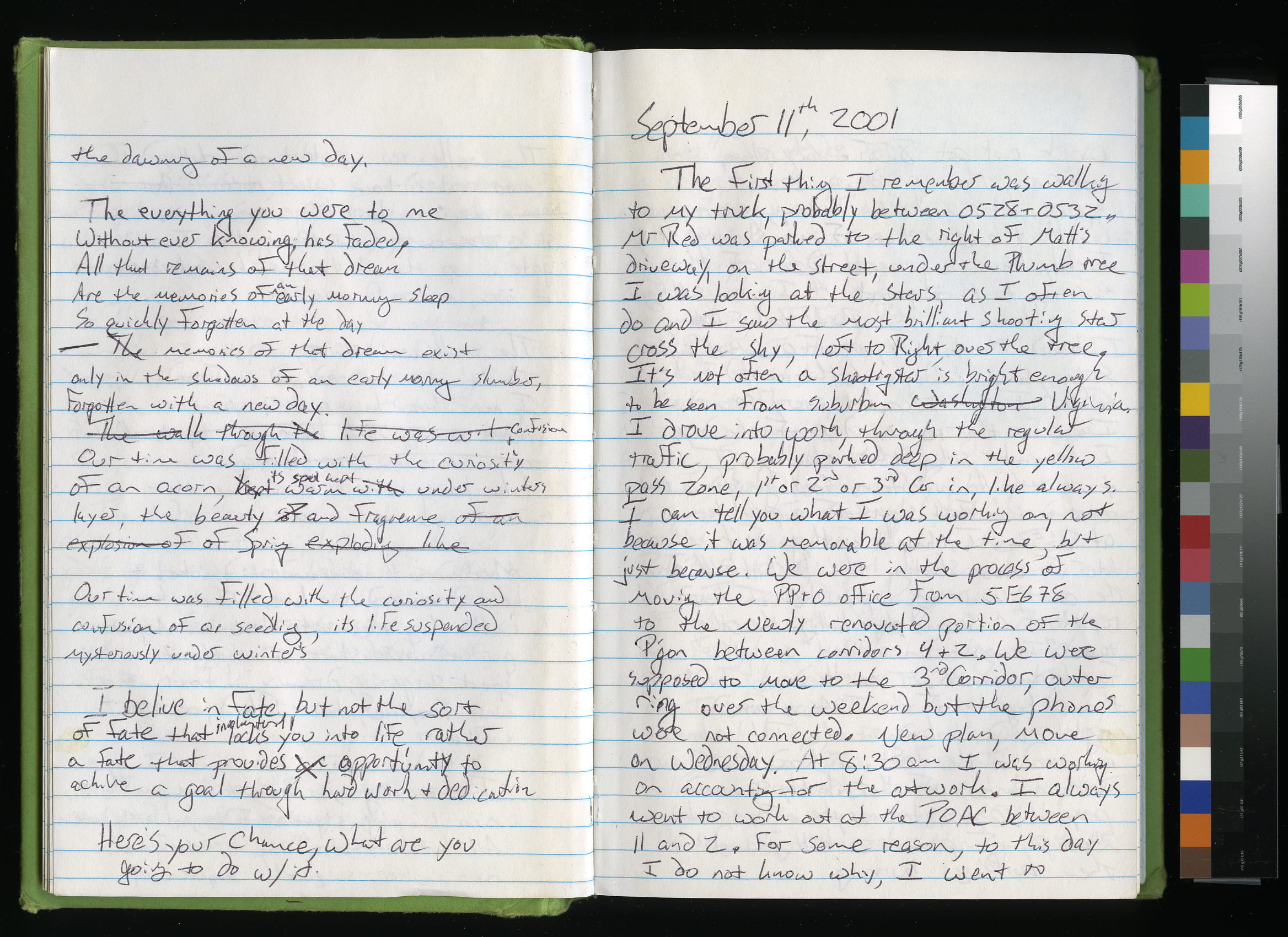

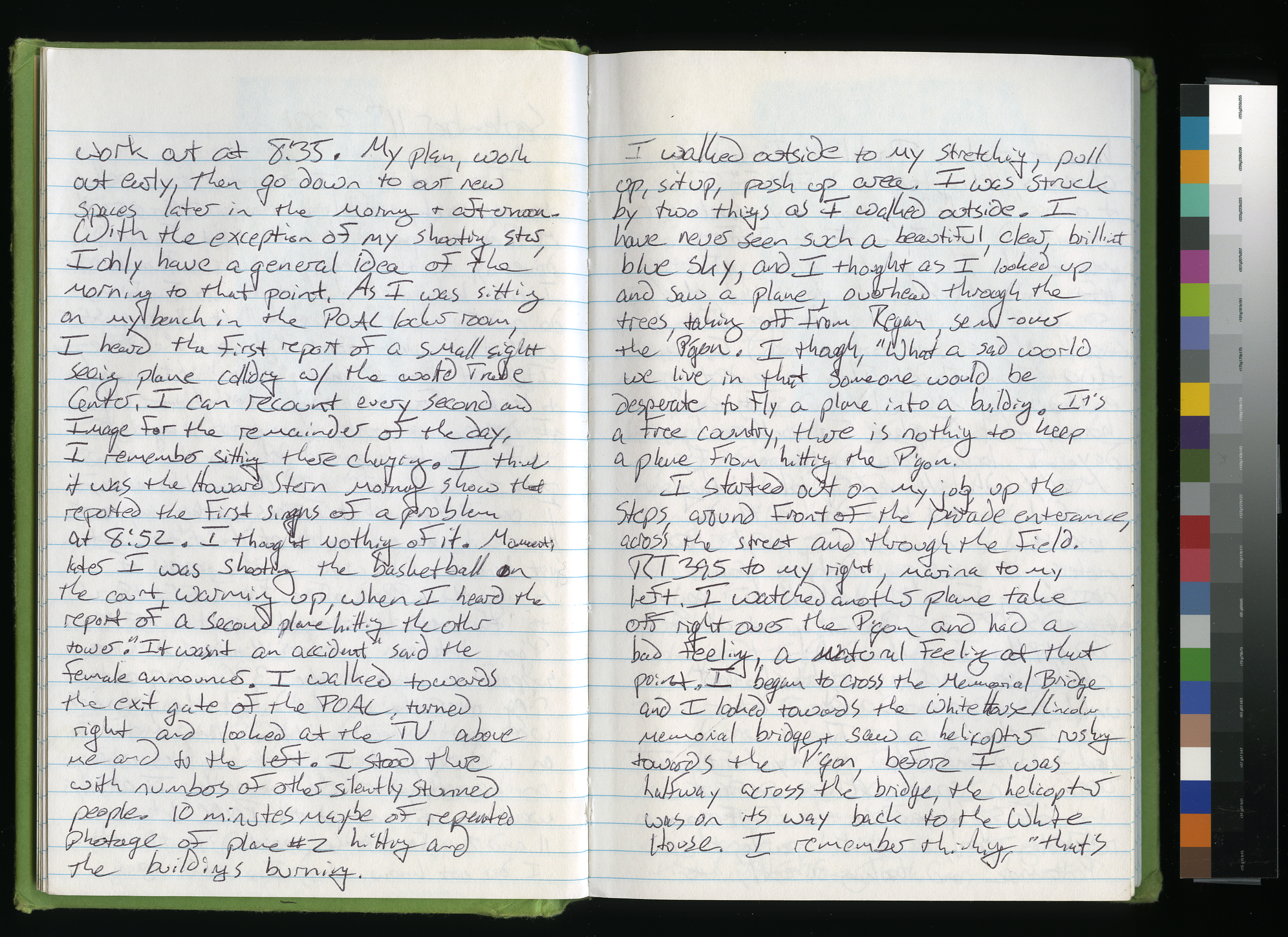

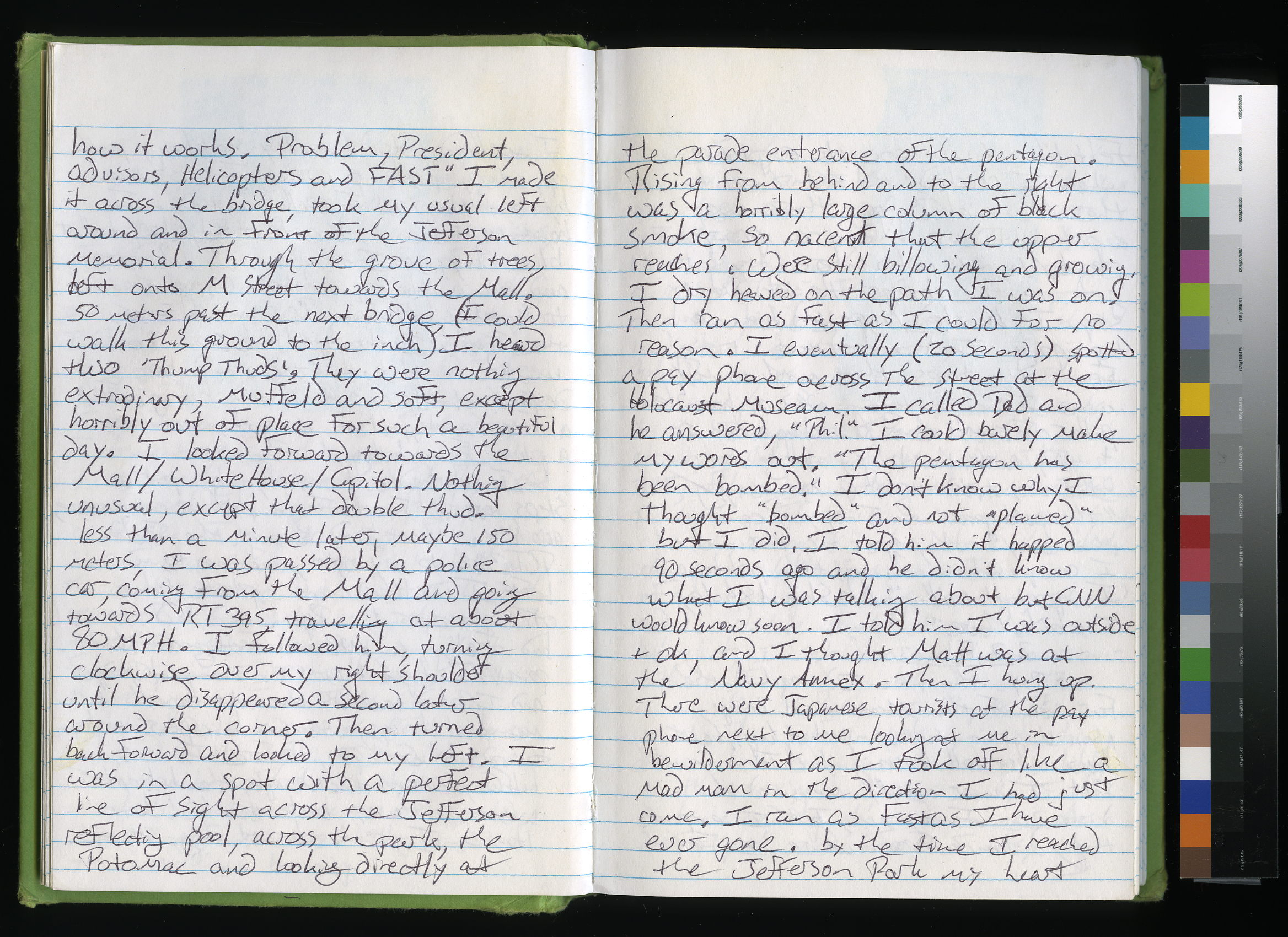

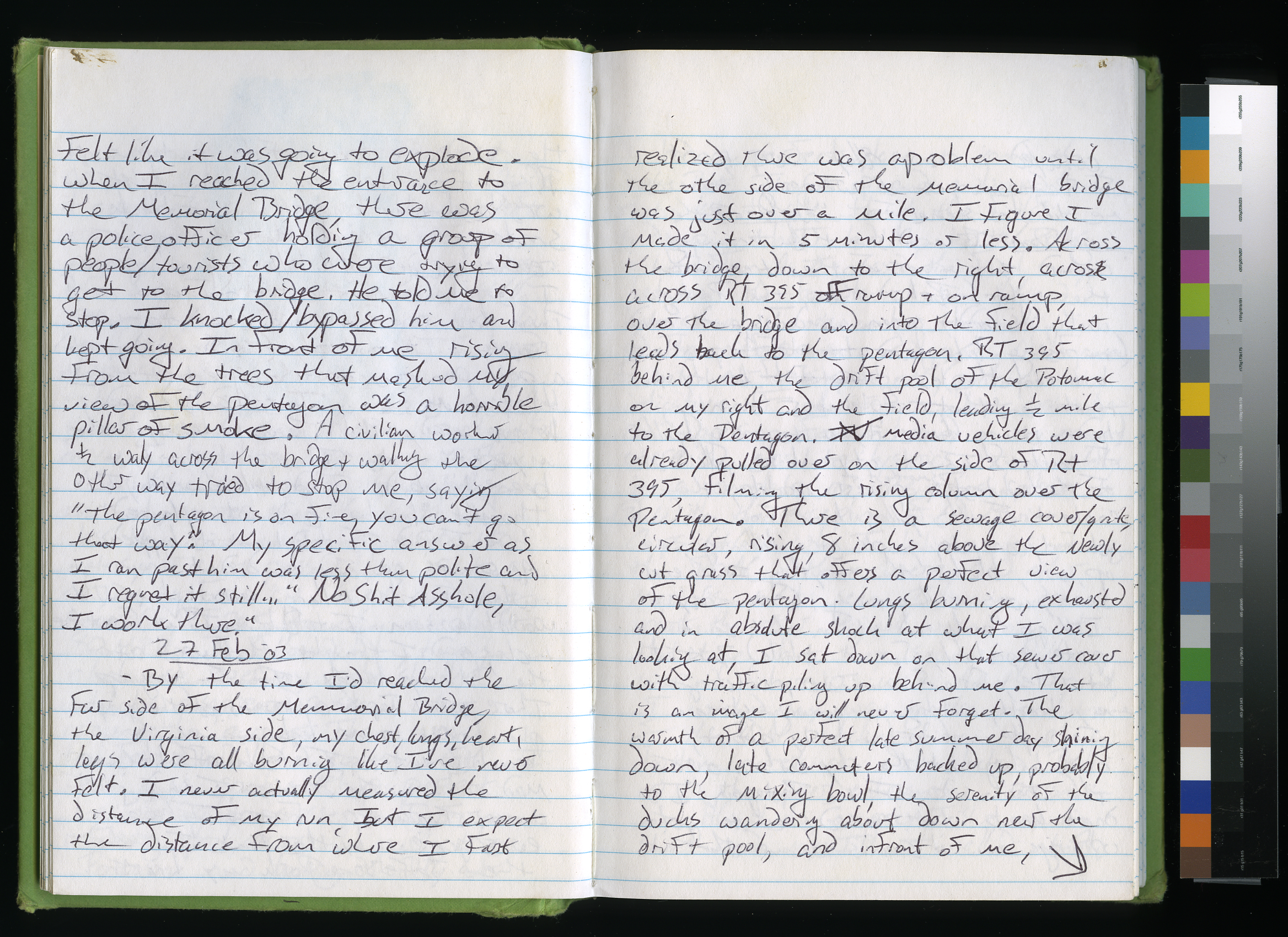

Journal Entry

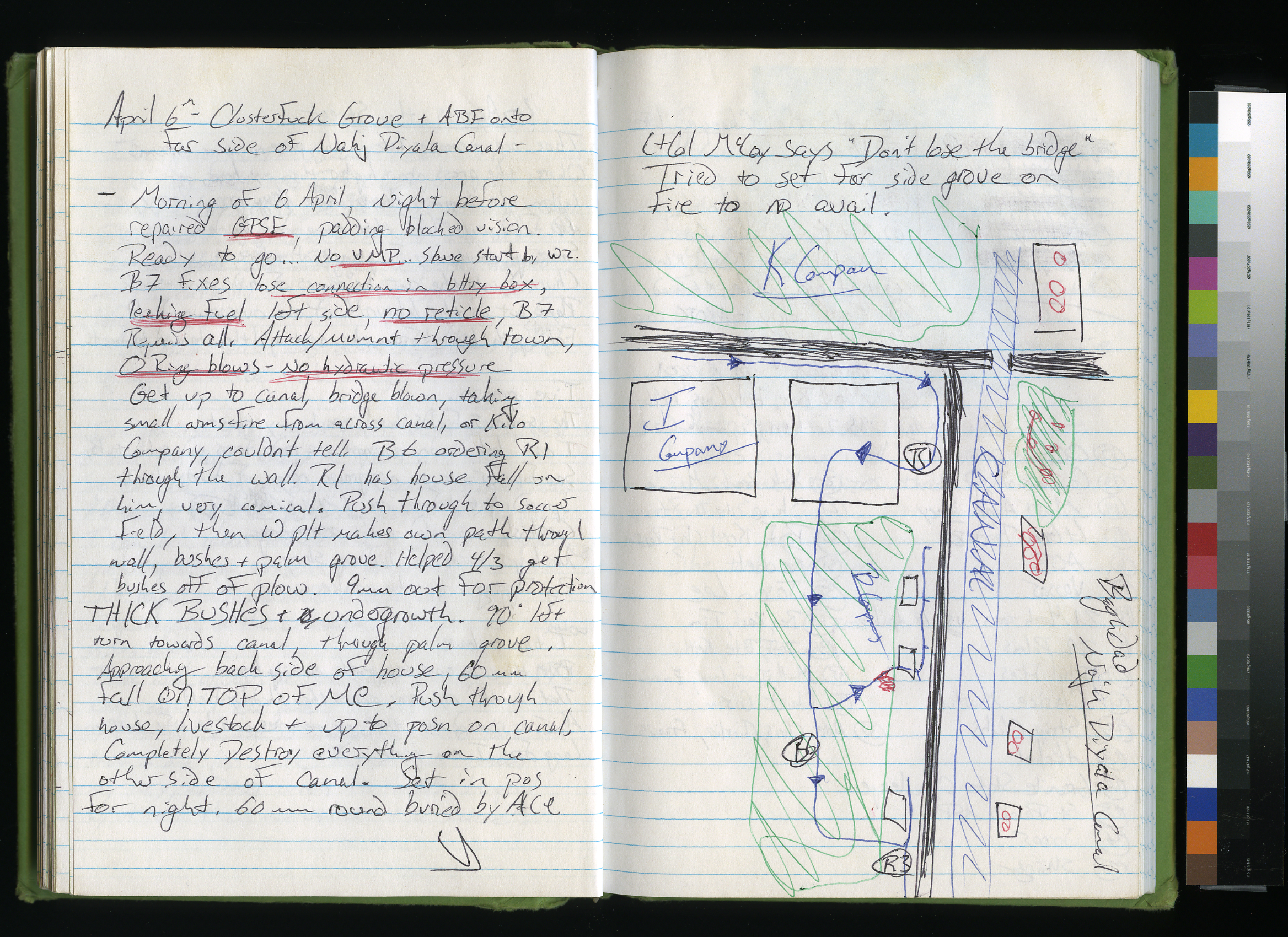

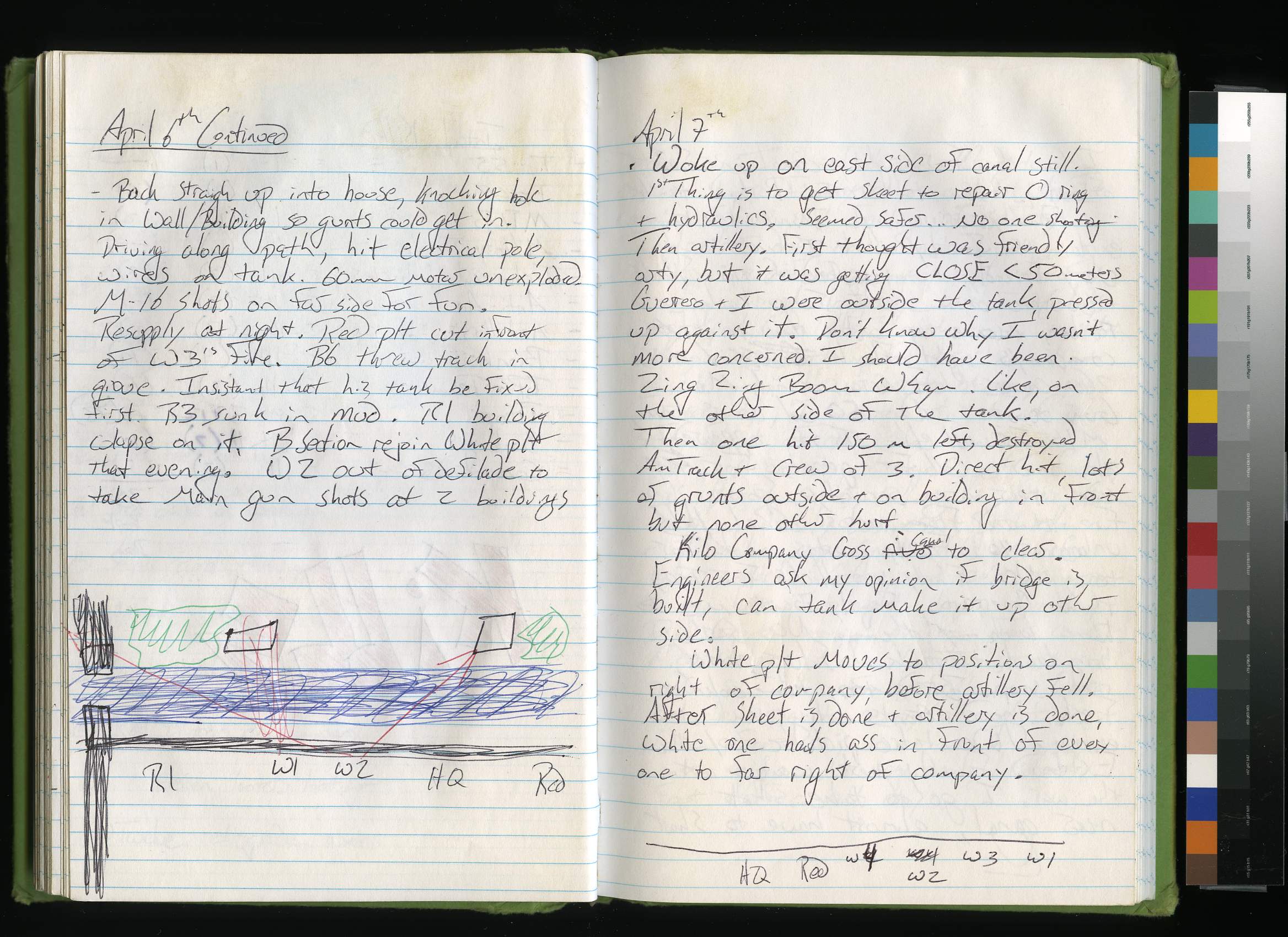

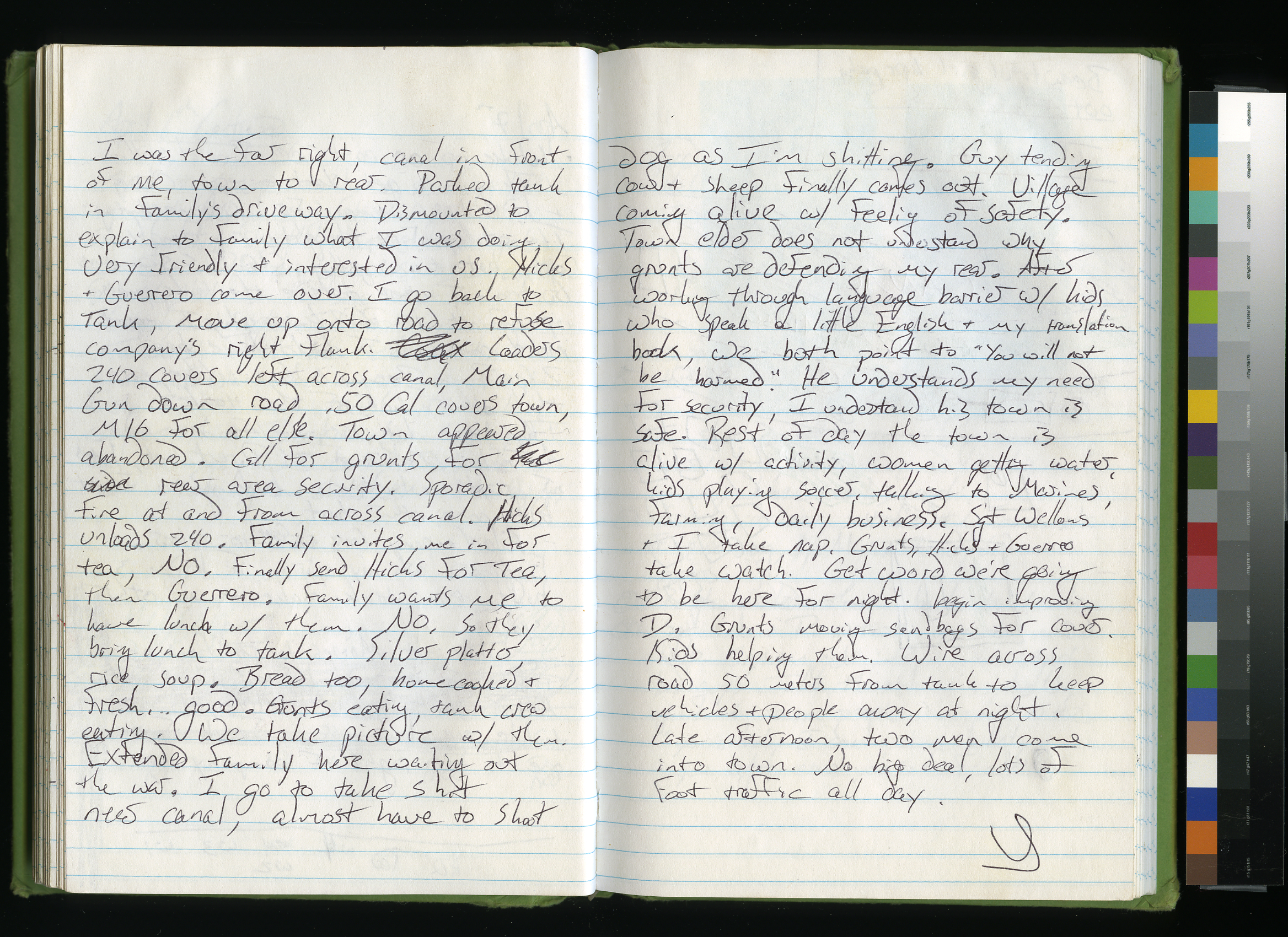

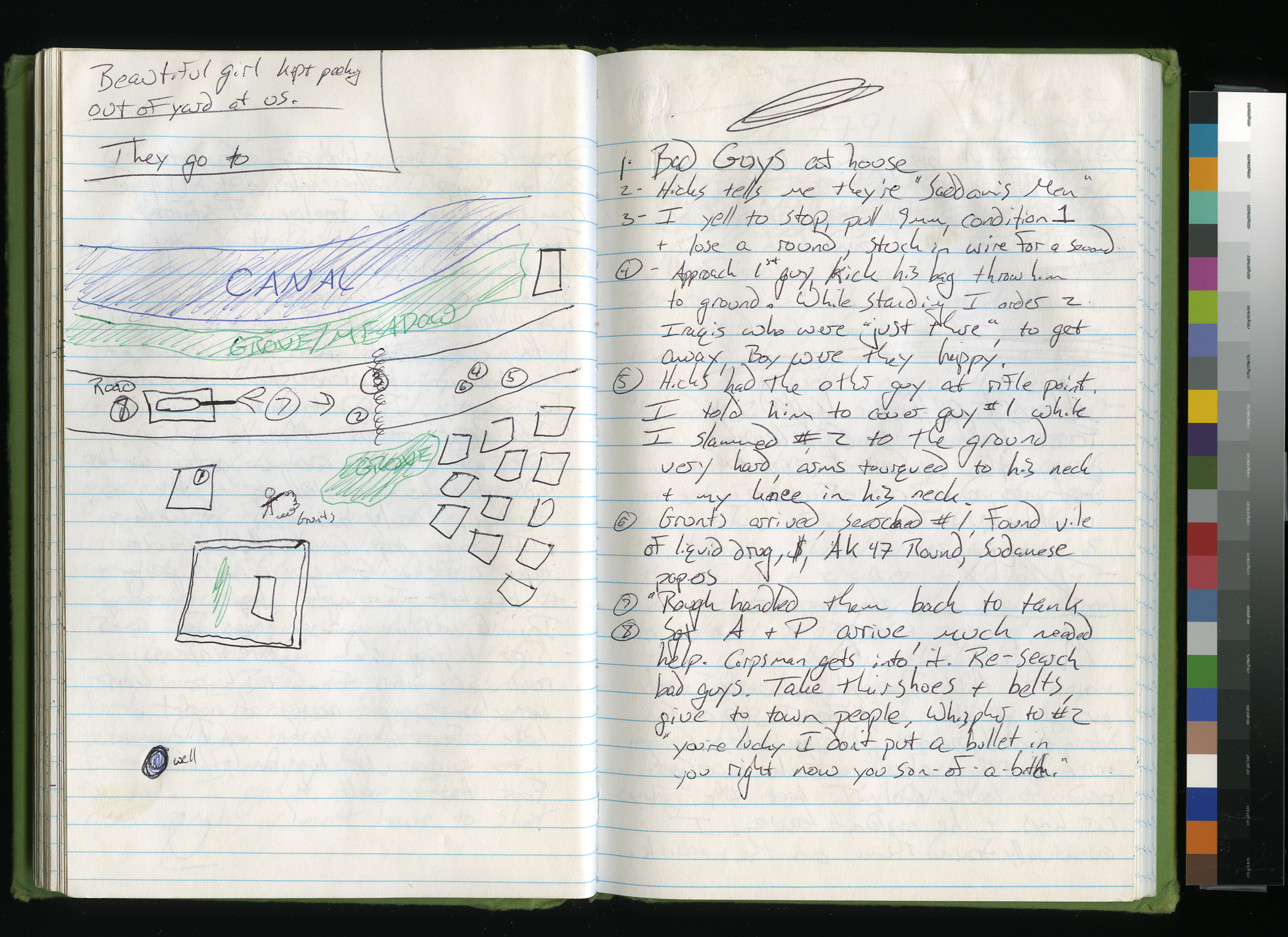

From my journal of April 6th - 8th, 2003.

6th April

The clattering of tracked vehicles and hi revving diesel engines jerks me awake at 0430. Its still dark and I ache from sleeping on the ground in my clothes. I went to bed late after watching tracer rounds arc across the Baghdad sky in the distance. It takes me a few seconds to adjust to the familiar but unwelcome sound of an army readying for battle and the sulphuric stench of exhaust fumes belching from an Abrams Tank a few feet away.

We pack quickly and silently and move back towards the Baghdad highway following Kilo Company AmTracs. We pass the ceramic portrait of Saddam on the traffic circle and the carcass of a man killed the day before; dogs are eating his face.

We move fast towards an Iraqi military base, drive up the scruffy road and stop outside the abandoned Officers mess. We wait, Marine time, it could be five minutes and could be 5 days. Hours pass in the sun, and I watch the thermometer on the dashboard rise. It's 47 degrees celsius. The flies are sapped, but even so, I don’t have the energy to fuck with them, I am just trying to keep it together and stay motionless - any movement generates heat. No one, save a few looters who pass by with war trophies, moves.

B Company tanks splinter the palm trees on the left as they lurch to a position out of sight where the road bends before making a straight shot up to Dyala Bridge 2 clicks away. Few things sound or look as menacing as tanks on the move, they are as loud as a foundry, and unlike most other vehicles or planes you can’t see the pilot, blind heavy metal monsters of war.

Incoming rocket-propelled grenades burst in the sky above our heads and a Marine screams that they are coming from some houses 400 yards away. The tanks fire into houses and 50 cal machine gun and assault rifle spit, the smell of cordite drifts through the palm trees and the once silent grove is now smoking and animated as orders come down the radio for everyone to move.

I jump out of my car with a camera and small bottle of water in the back pocket of my pants and run forward past the Marine command post up to Kilo and India Companies parked at a road junction firing grenades and 50 cal into houses 200 yards away. The Marines are moving forward on foot preparing to take Diyala Bridge.

Marines in chemical suits run through the dust and smoke that hangs at street level securing house to house. Plastic explosives break down the doors, Marines rush in, kick down doors and sweep from room to room, tension as they move up the stairs. Blocked door - 2 shots through the latch, sledgehammer, door open, nothing, move to the next house. Senior NCO’s scream at the Marines, “move, don’t fucking bunch up – where’s fucking First platoon?”.

A grenade flies over a wall; I lean into the wall as the vibrations of the grenade hit me like a sandbag. Dust billows through the already smoky air, and four Marines scamper over the wall, rounds through the door of the house on the other side. I wonder who was hiding inside who lives in these houses. 2 more shots through the door and on up the street. Its too hot, my eyes sting from the sweat and the cordite, my mouth is too dry to open. I am dehydrating and my head aches. I am wearing only a shirt; the marines wear chemical suits, flak jackets, and helmets. I am glad I am not a Marine but wish I was closer to 18.

I can’t hear anything but the gunfire. The noise is fine, battlefields are always loud, and the only thing I can do is put it the back of my mind and only try to allow in the sounds that are important. The sound of air breaking near your ears makes you wince; the bullet displaces air so fast it cracks. Bullets and shrapnel travel faster than the speed of sound, so you never hear what kills you, as long as you hear it your fine, there is comfort in that.

Another door another grenade.

Three men clatter over the wall, heavy with gear, they land on the other side like heavy mail bags and confront three civilians cowering behind a car crying. I feel guilty; I hope they’ll know the difference between the Marines and me, but I doubt they will.

3/4 fights up to the bridge, mortars take a position in the charred remains of the open air street market on the banks of the canal next to Dyala bridge, still smoking from incoming 155’s. Gunfire and RPG’s incoming from the palm trees on the opposite bank, Lt Col McCoy calls in the artillery, an RPG explodes 10 yards away, I try to bury myself in the garbage around me, but it’s not deep enough. I just lie there grinding the earth trying to leave as small a target for whoever is firing at us as possible. Snipers shoot anything moving on the northern side; a tank takes out a house into which two women and a child fled moments before. I want to believe the Marines did not see them but I know they did.

The light starts to fail behind clouds of cordite and smoke. The battle comes to an end for the day; the combatants are tired, thirsty and hungry. Like men at war for thousands of years past I trudge back to my shelter to eat and rest. The sound of artillery and the evening air strikes howl in the city beyond.

I stink, and I have no clean clothes - so I do my laundry in a garbage bag using water from a pipe coming out of the ground. Soap powder and a couple of liters of water in a garbage bag will wash a lot of clothes, I also wash, naked in a line of naked men standing in the entrance to a municipal building washing the stain of war off our bodies in silence. I lay my clean clothes on the road to dry on the heat of the tarmac. Enrico and I refuel the car from the last of our jerry cans and sleep restlessly, dressed with our boots on on a blanket in the gutter next to the car.

7th April

0430 wake up, pack the car, squeeze a foil envelope of peanut butter into my mouth, drink a mouthful of warm water, fold my laundry and drive to 20 yards short of the bridge.

An APC is parked on the left of the bridge, mortars on the right. Outgoing 155’s light up the palm grove on the north side of the river, mortars and machine guns take care of the residential area on the left. The usual cocktail of overwhelming firepower before an assault. I guess they are going for an infantry assault on the bridge sometime soon. I see mortars on the right and wander over to take some photographs.

Iraqi 155’s walk towards our position, rows of exploding shells moving in a line until they land right on top of us, metal flying everywhere, confusion: Incoming and outgoing, it all feels like incoming it's so damned loud and so close. A Marine APC explodes 10 yards away; the turret flies in the air like a plastic toy. I run across the road through a cloud of dust and black diesel smoke. 2 dead Marines on the ground, the wounded crying for help. Marines not wounded swarm the area. The tension and anger rise. Enrico and I photograph.

Kilo and India companies start to move, run for the bridge, step over the dead boy covered in flies that Jack shot last night and span the holes in the floor with boards. Grunts charge the northern banks. Everyone is shouting, and bullets cut through the clouds of smoke and dust.

Iraqis in every possible death pose litter the street, fried to a crisp with their clothes burned off, rigor morticed, some intact - delicately pierced by a sniper round or exploded and melon red, fresh, bleeding. The road is filled with shards of metal, and concrete from destroyed buildings - like a lava field it's hard to walk without twisting your ankle. Its quiet now and the pain and violence are overwhelming.

Shrapnel and concrete crunch underfoot as the Marines move house to house. An old grey-haired civilian is lying slumped with his head rested against the steering wheel of his truck, he looks like my grandfather Dick, the difference being that Dick died of a stroke and didn’t end up losing the back of his head. I imagine his wife waiting for him to return from work.

We reach the end of the block, bridgehead for the Division now secured. Kilo takes the open ground and digs into the dirt on the west side of the road, India is still moving through the palm grove on the east. Marine snipers take up positions on either side to hit anyone coming our way.

Heavy air strikes and artillery north of us, very close. A blue minivan approaches from that direction, the snipers fire warning shots, and it turns away. A white pick up approaches, the snipers kill the driver, a soldier in uniform, fair game. The blue minivan returns, the sniper's fire warning shots but the grunts open up simultaneously with everything they have, the minivan bursts like a cherry, Captain Norton screams “ceasefire – wait for the snipers” but its too late. Five civilians are bleeding to death, isolated.

8th April

Five cars lie idle in the middle of the road when I return the next morning, Enrico found two survivors who had stayed in the blue minivan all night. They had been fleeing the US bombing behind them when they drove into the Marines. They had no idea what they were driving into.

The Battle for Dyala Bridge, April 6th & 7th, 2003: Photography by Gary Knight

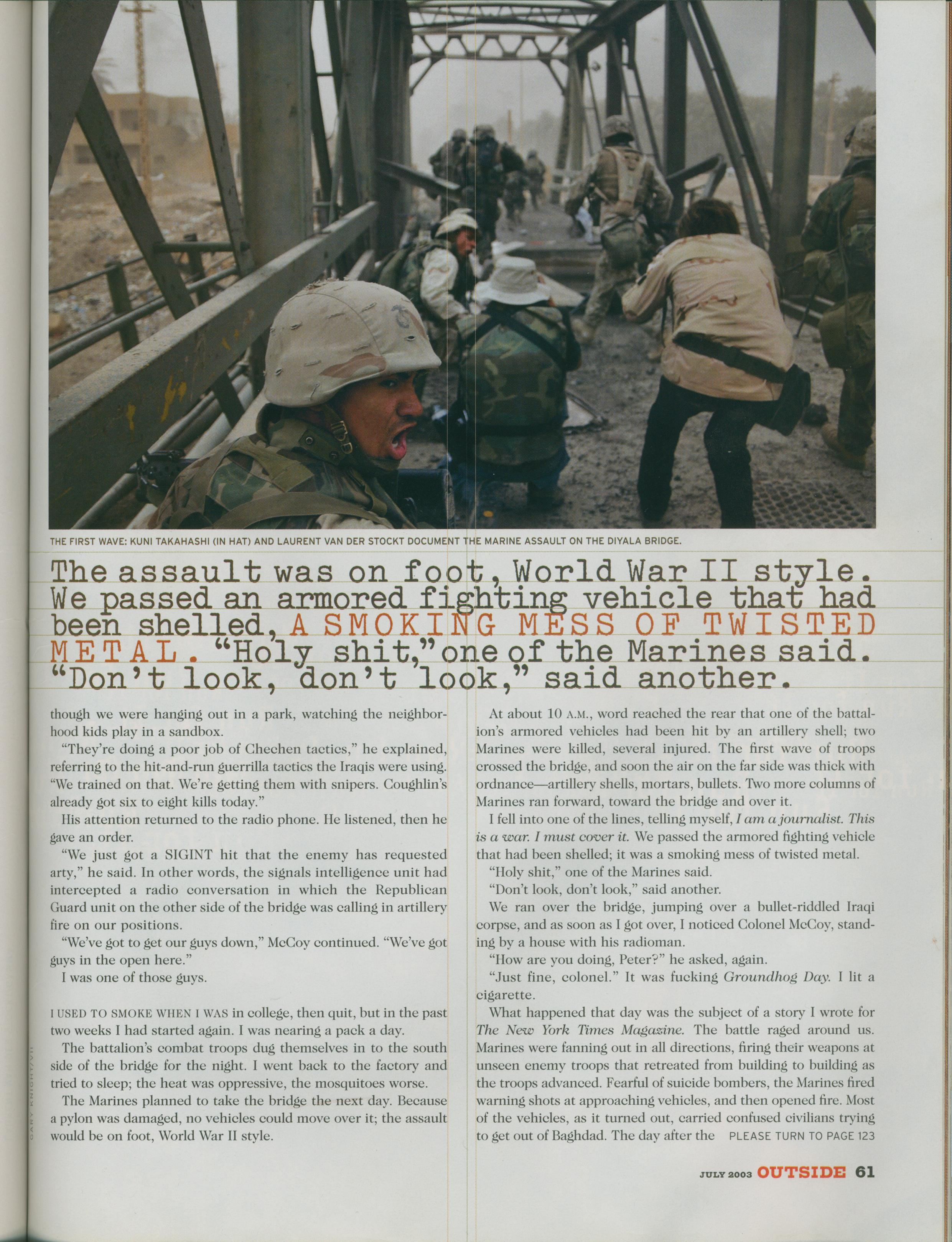

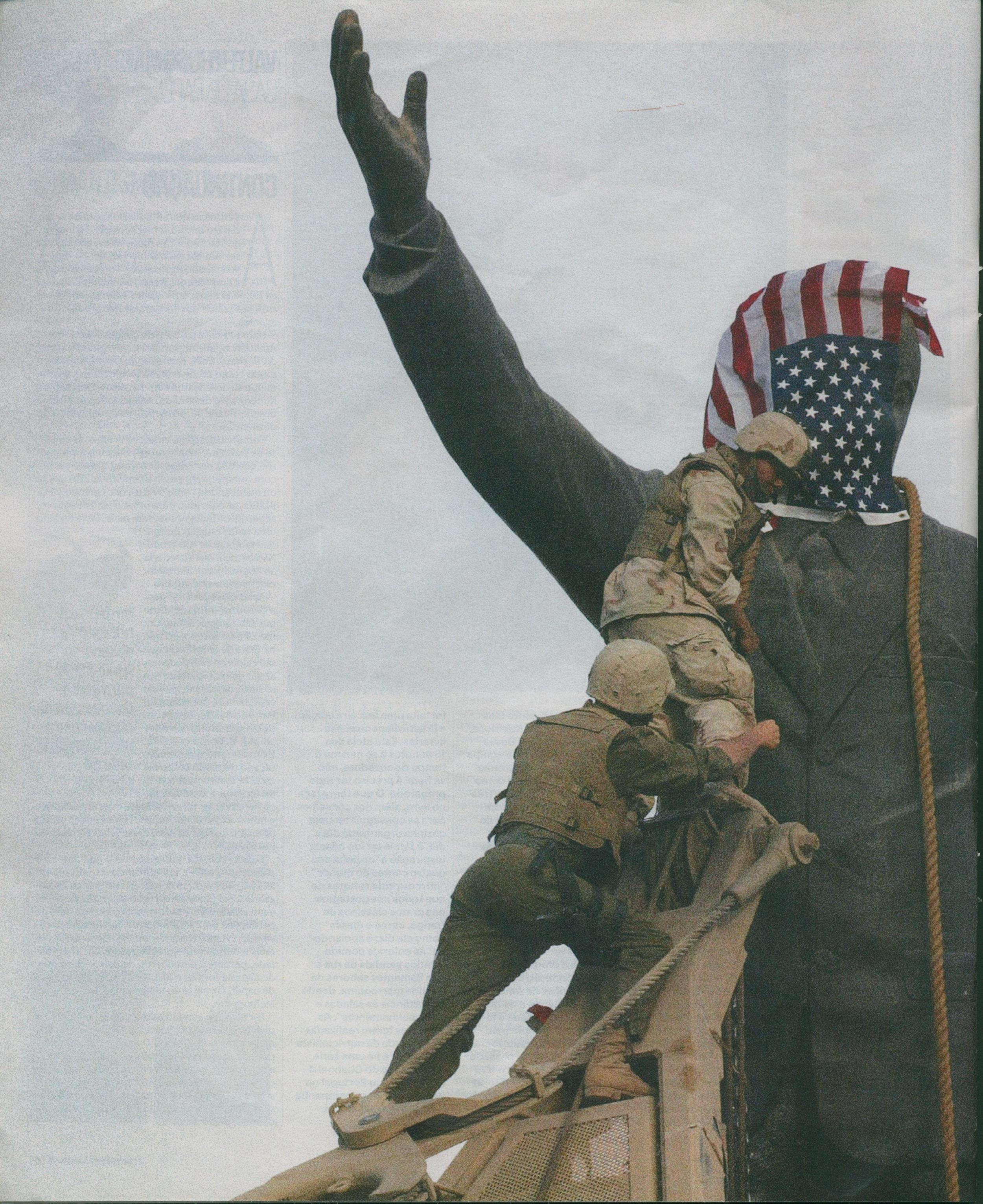

Looking backwards at the war

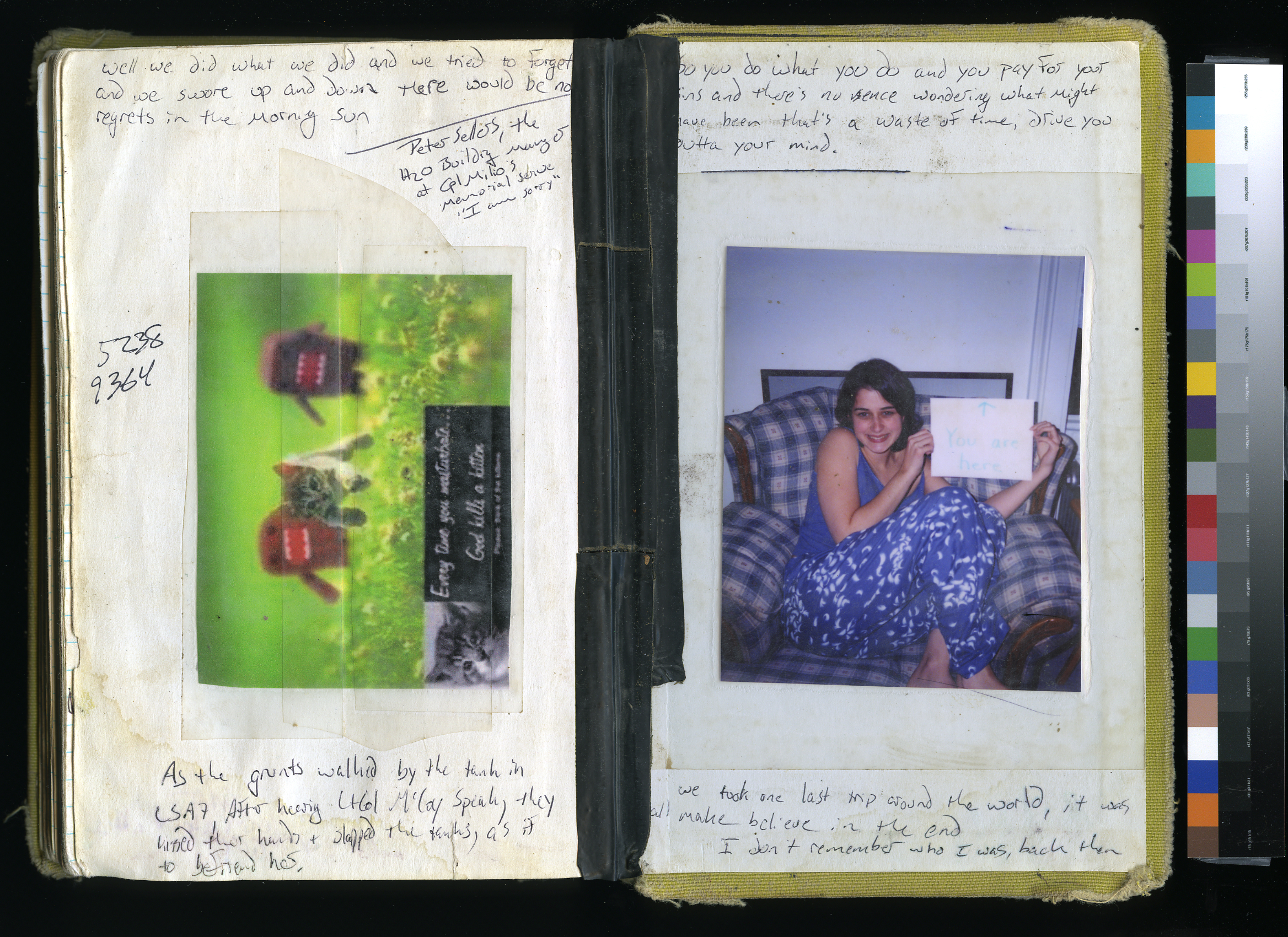

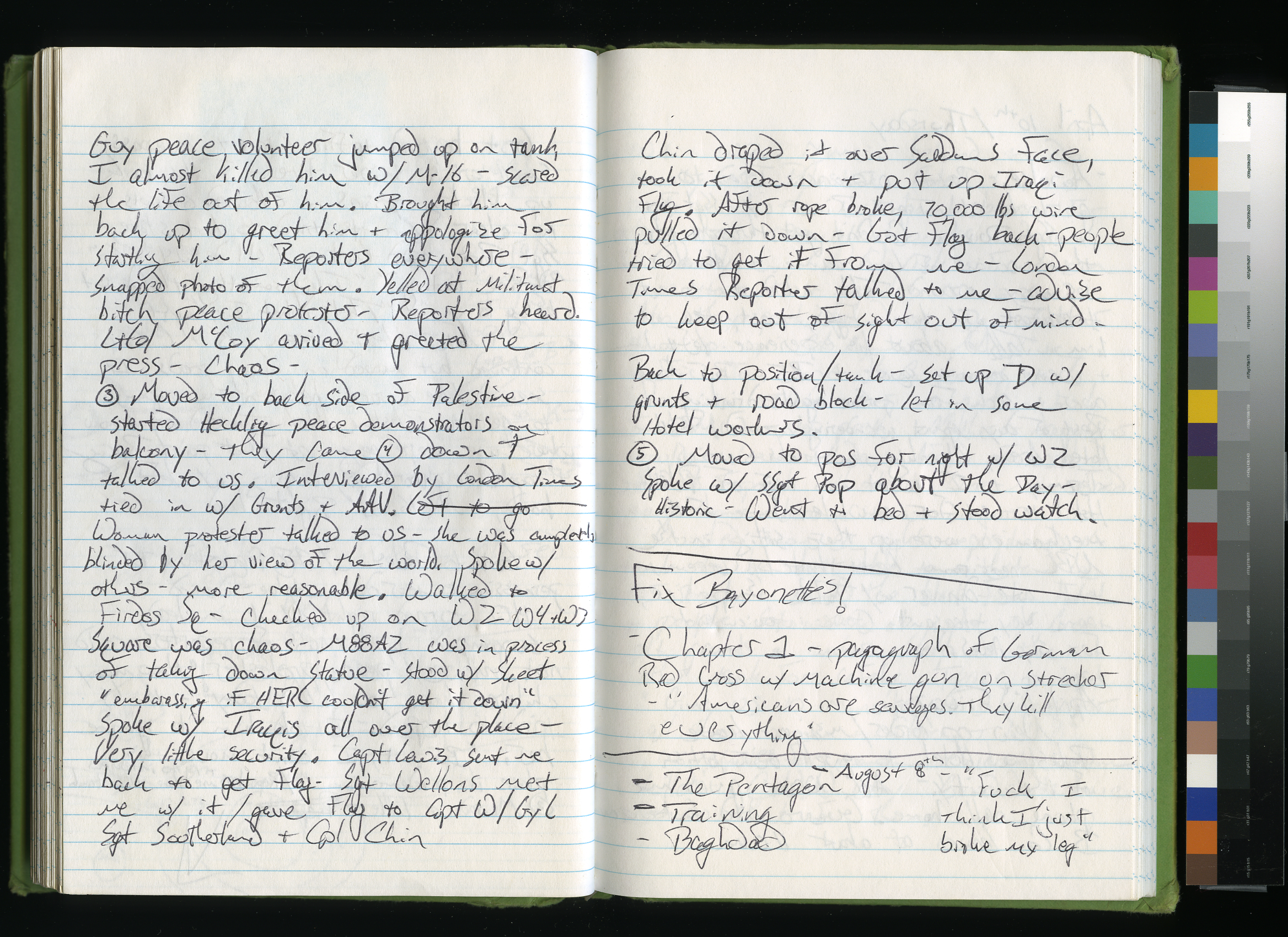

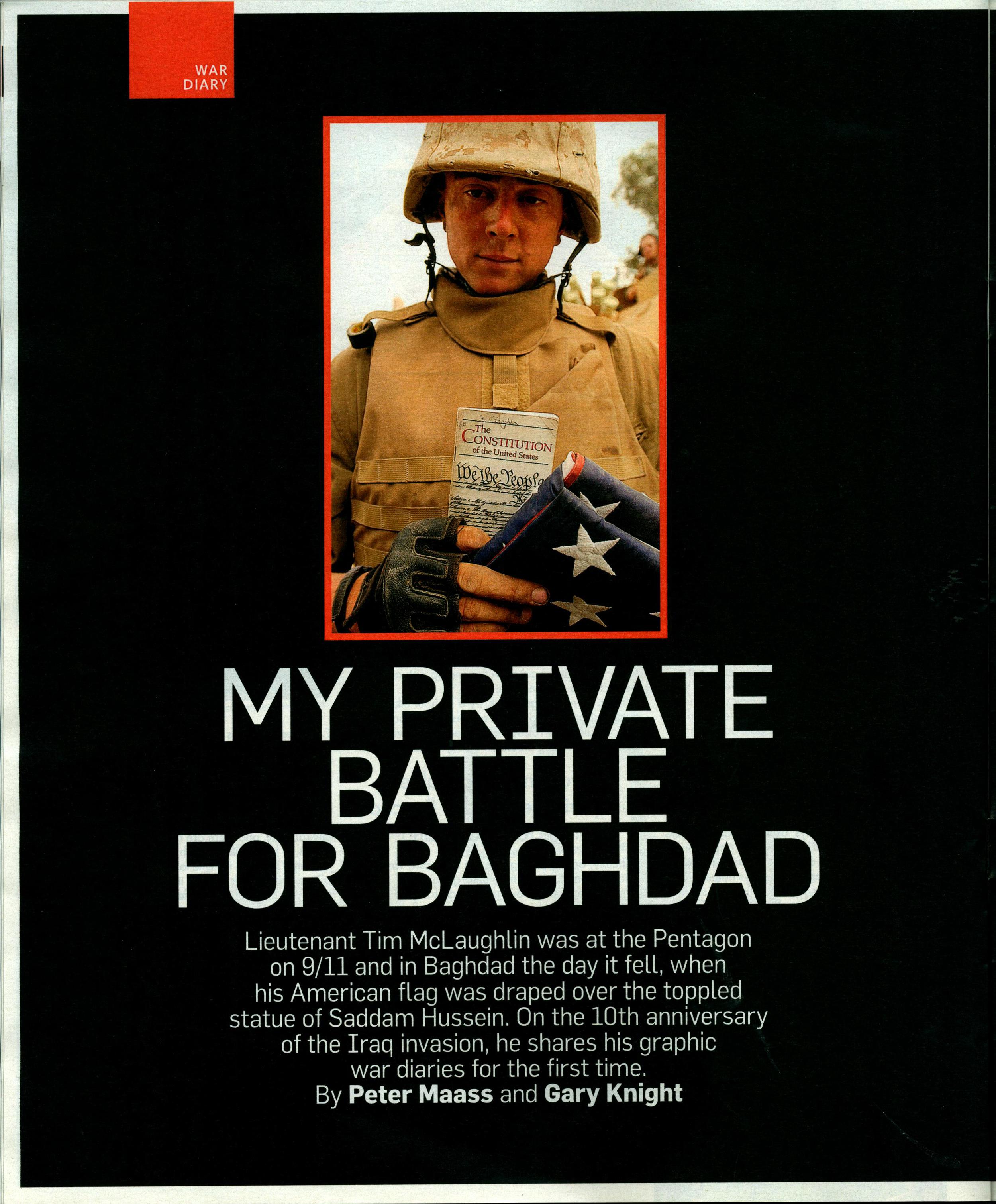

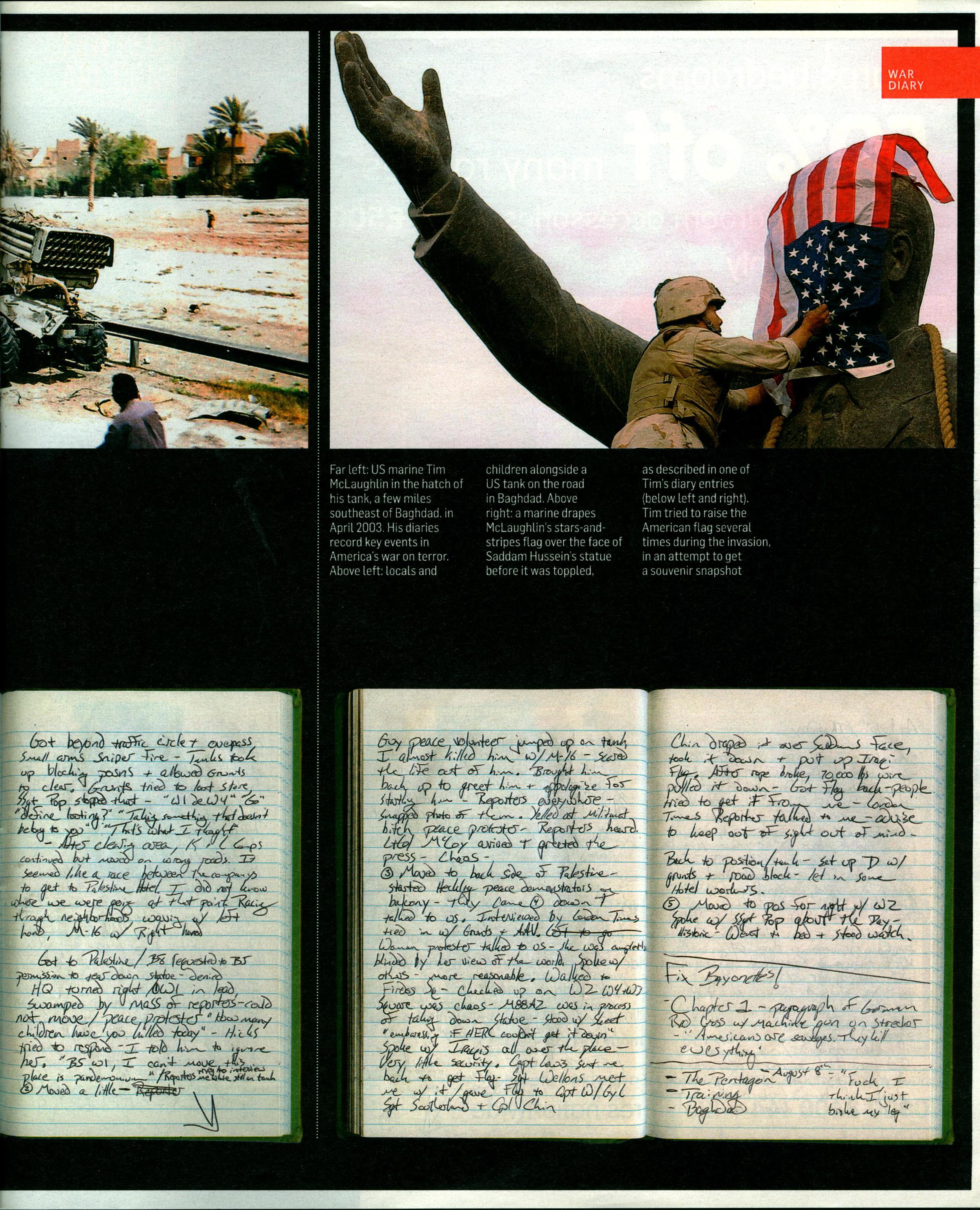

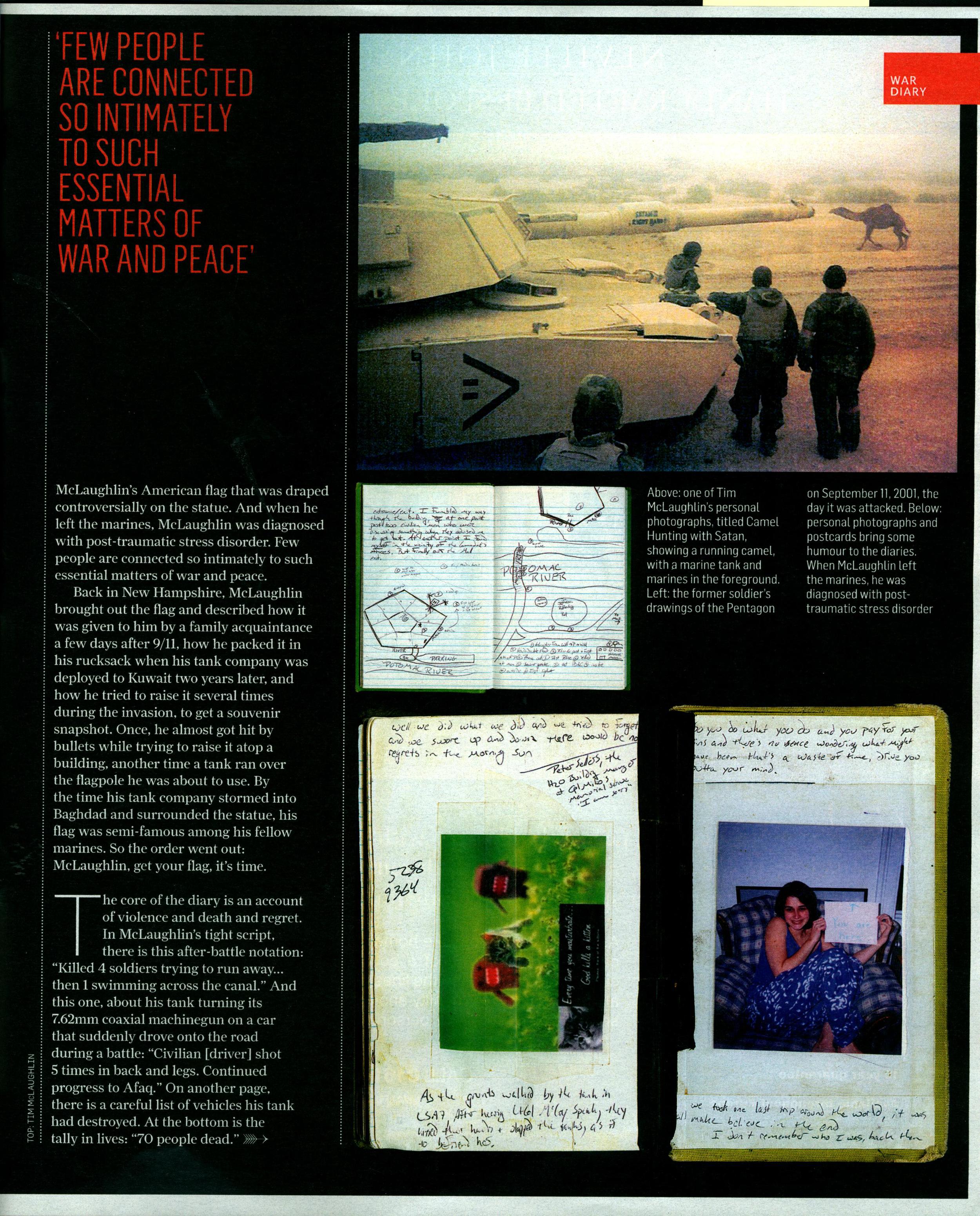

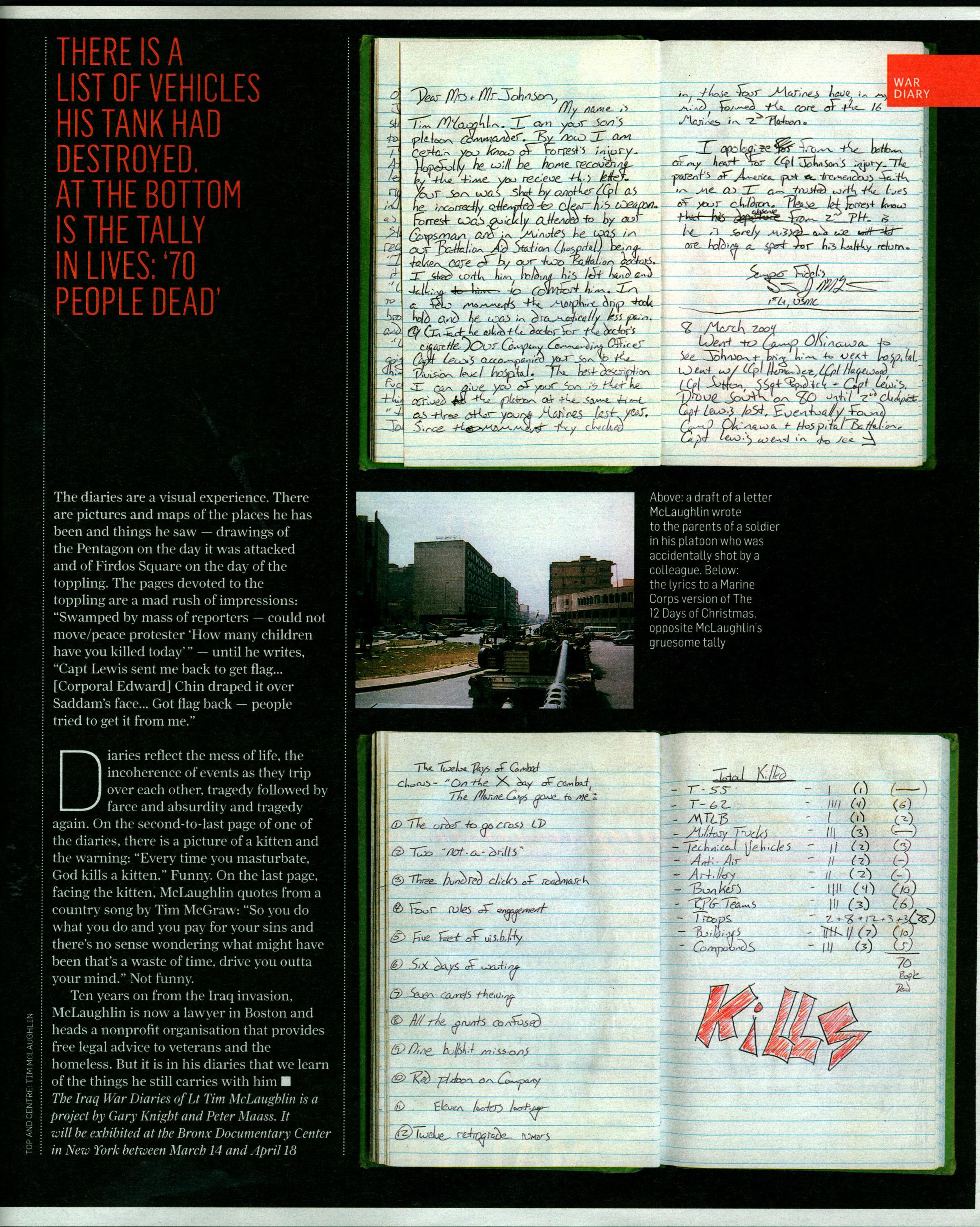

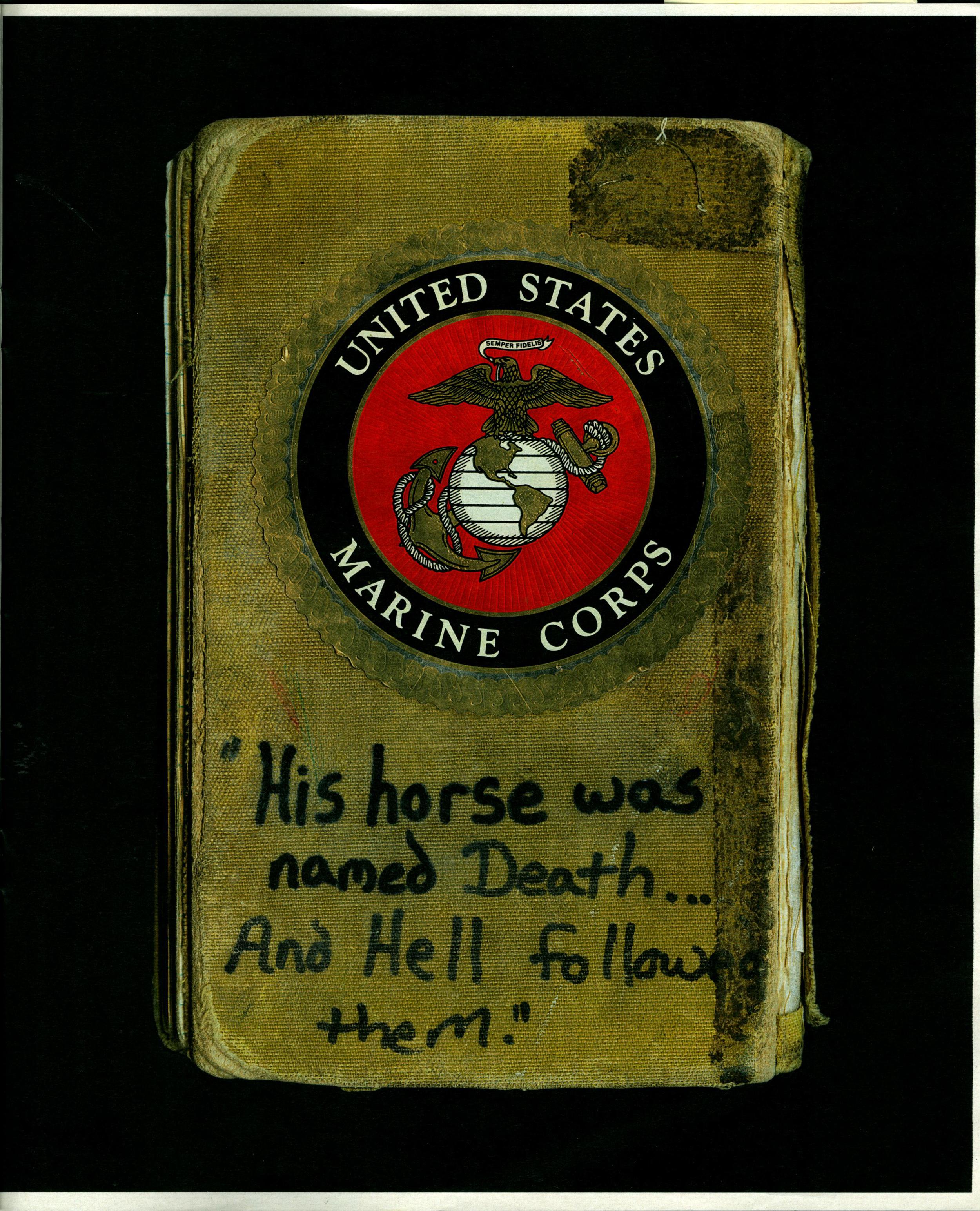

In 2009, Peter Maass and I found ourselves at Harvard on Nieman Fellowships. Peter was researching a story about the raising of the US flag on the statue of Saddam in Firdos Square and the subsequent pulling down of the statue by the 3rd Battalion 4th Marines. Lt Tim McLaughlin was the owner of that flag. Peter went to meet Tim and started a conversation with him that touched off a collaboration between the three of us. Our project examined our experiences of the same events during the invasion. Our differences in interpretation were informed by the contrasting ways we participated in the war, the small but significant difference of angles of view, and the varying access to information we had at the time. In 2013, to mark the tenth anniversary of the invasion, we created an exhibition containing my photography, Tim’s diaries, Peter's words, and personal snapshots by the three of us.

Exhibition

War Diaries Exhibition at the Bronx Documentary Center

“The show is a stinging rebuke of the news media’s early unquestioning coverage as well as a window into the nature of war.”

Personal Photographs: Photography By Gary Knight, Marine LT. Tim McLaughlin and Peter Maass

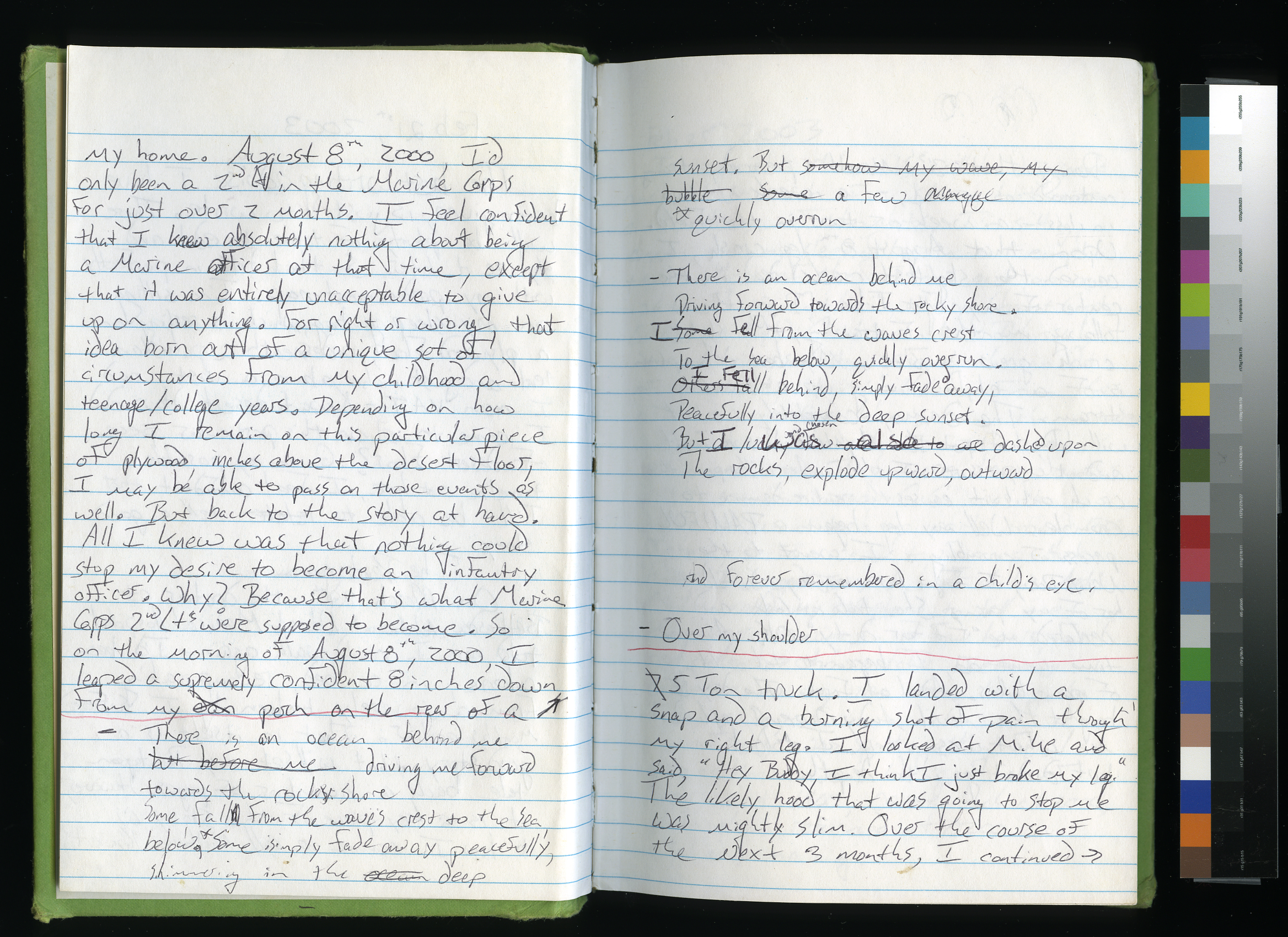

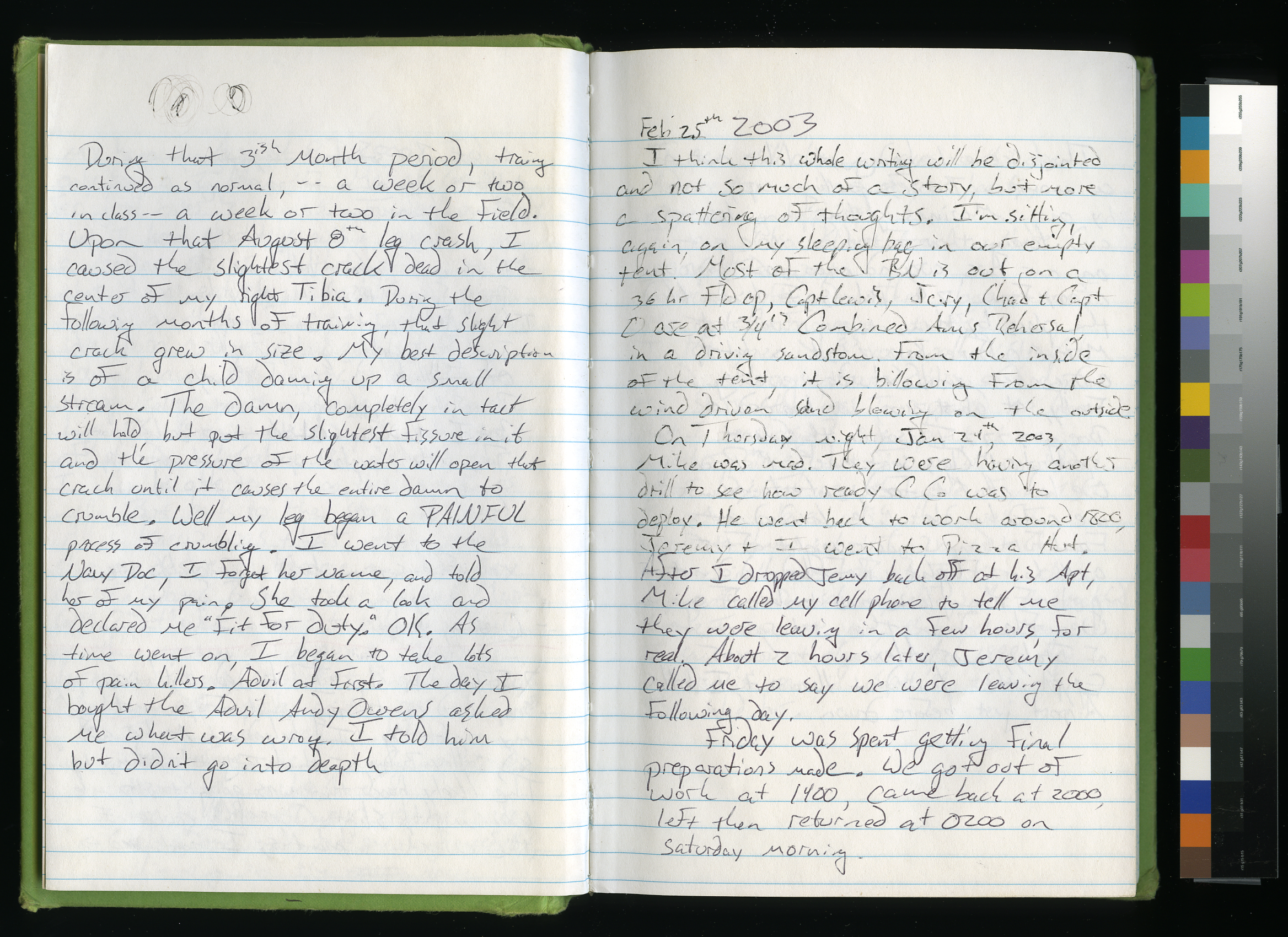

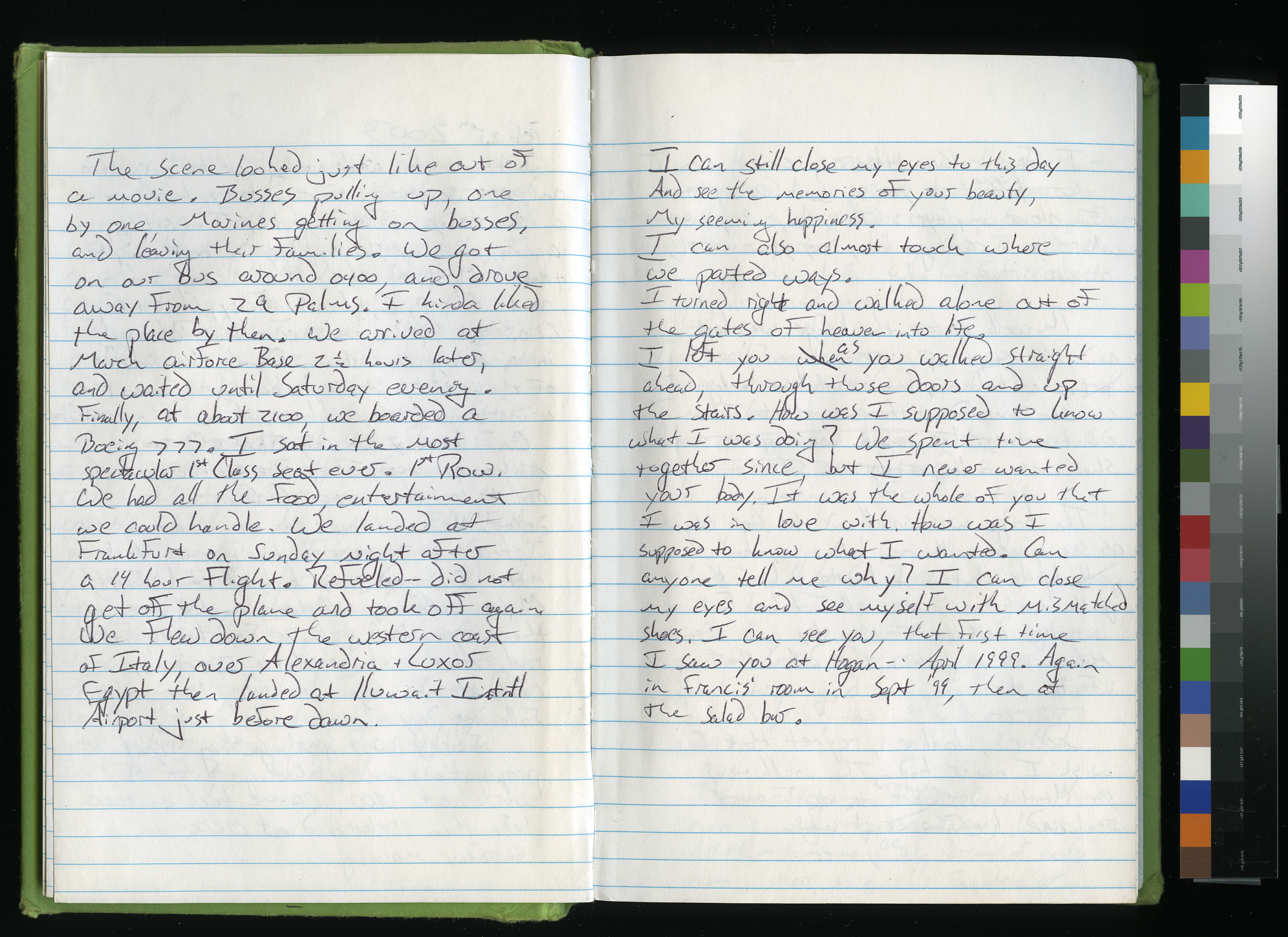

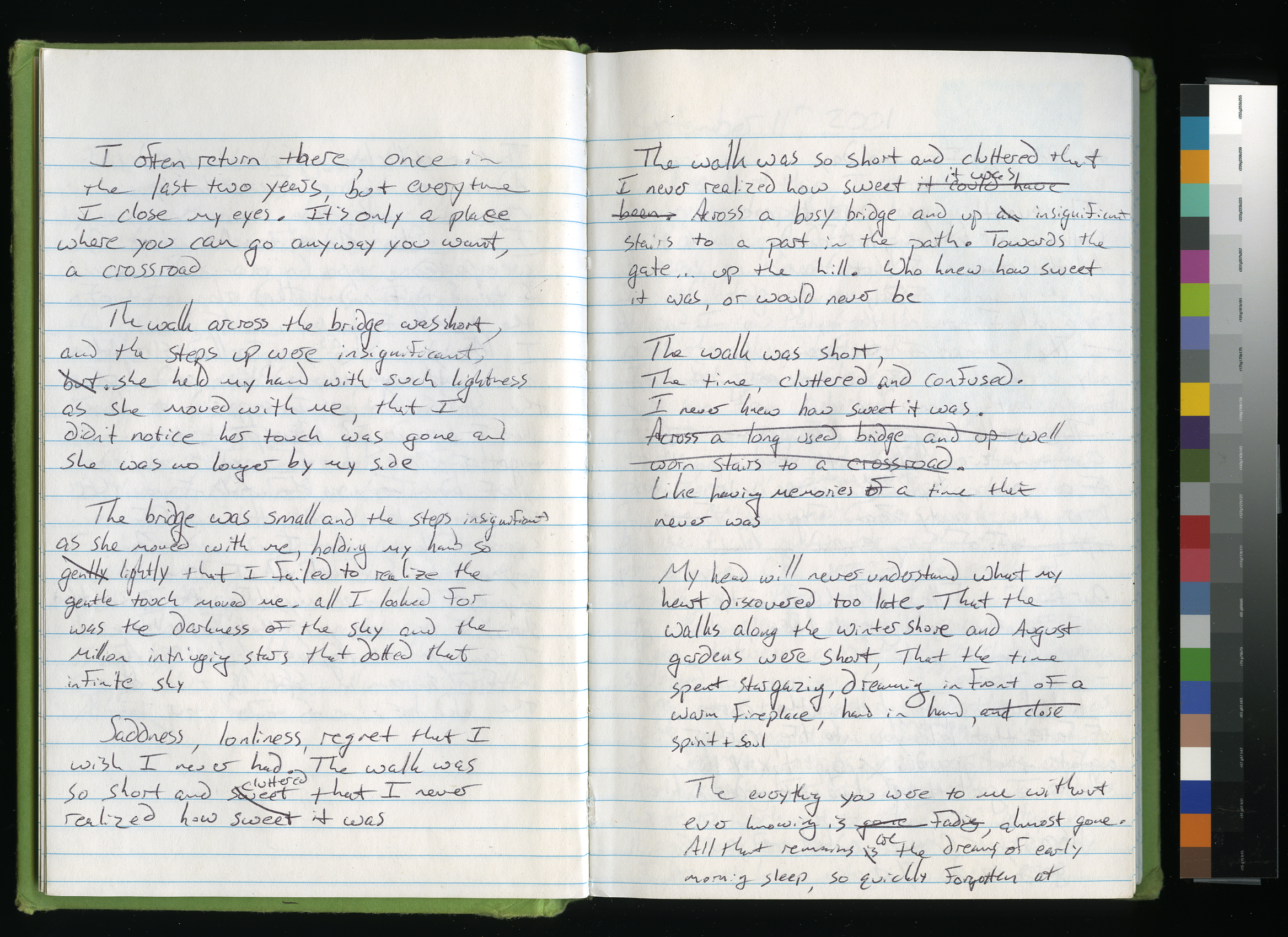

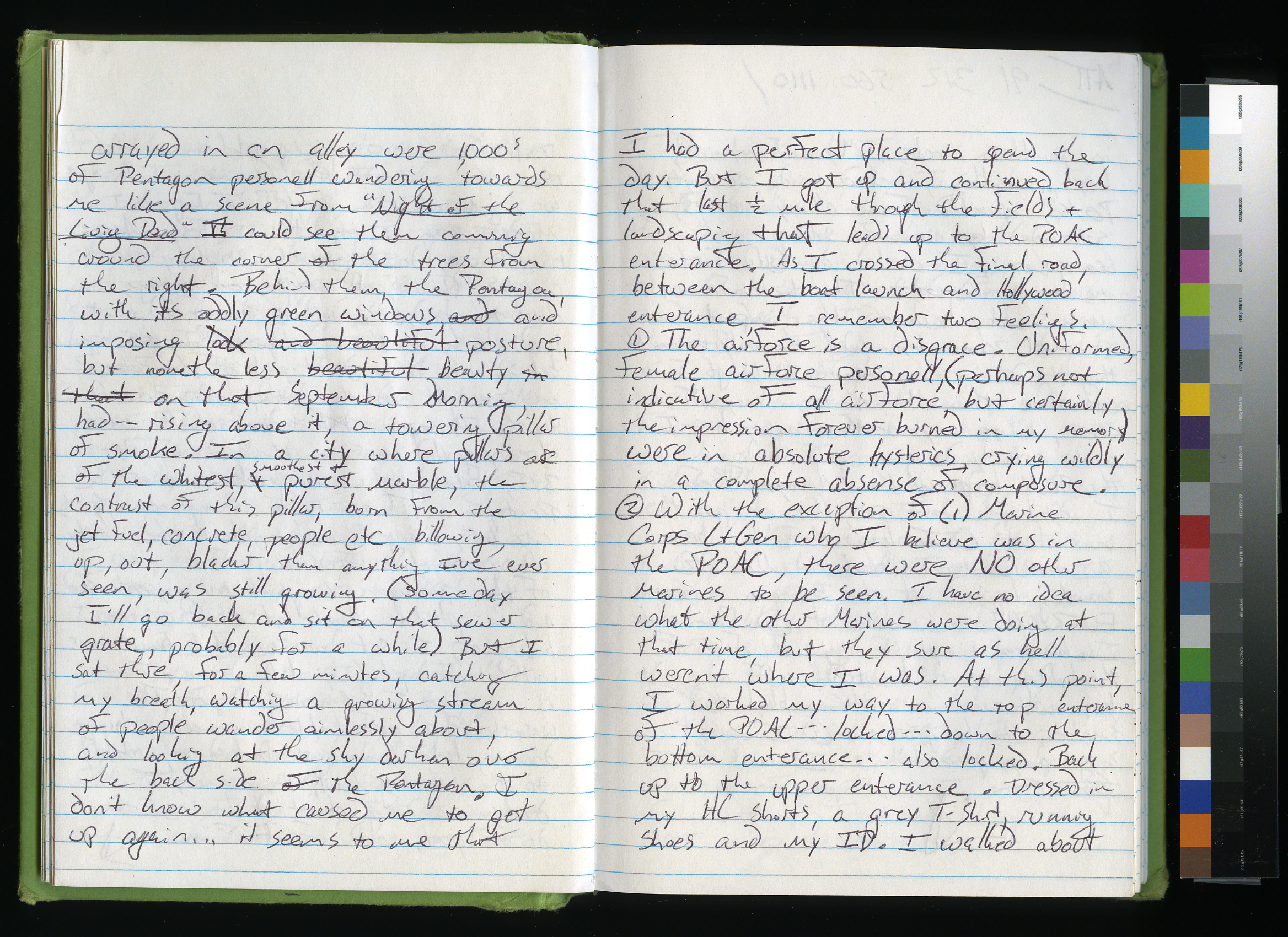

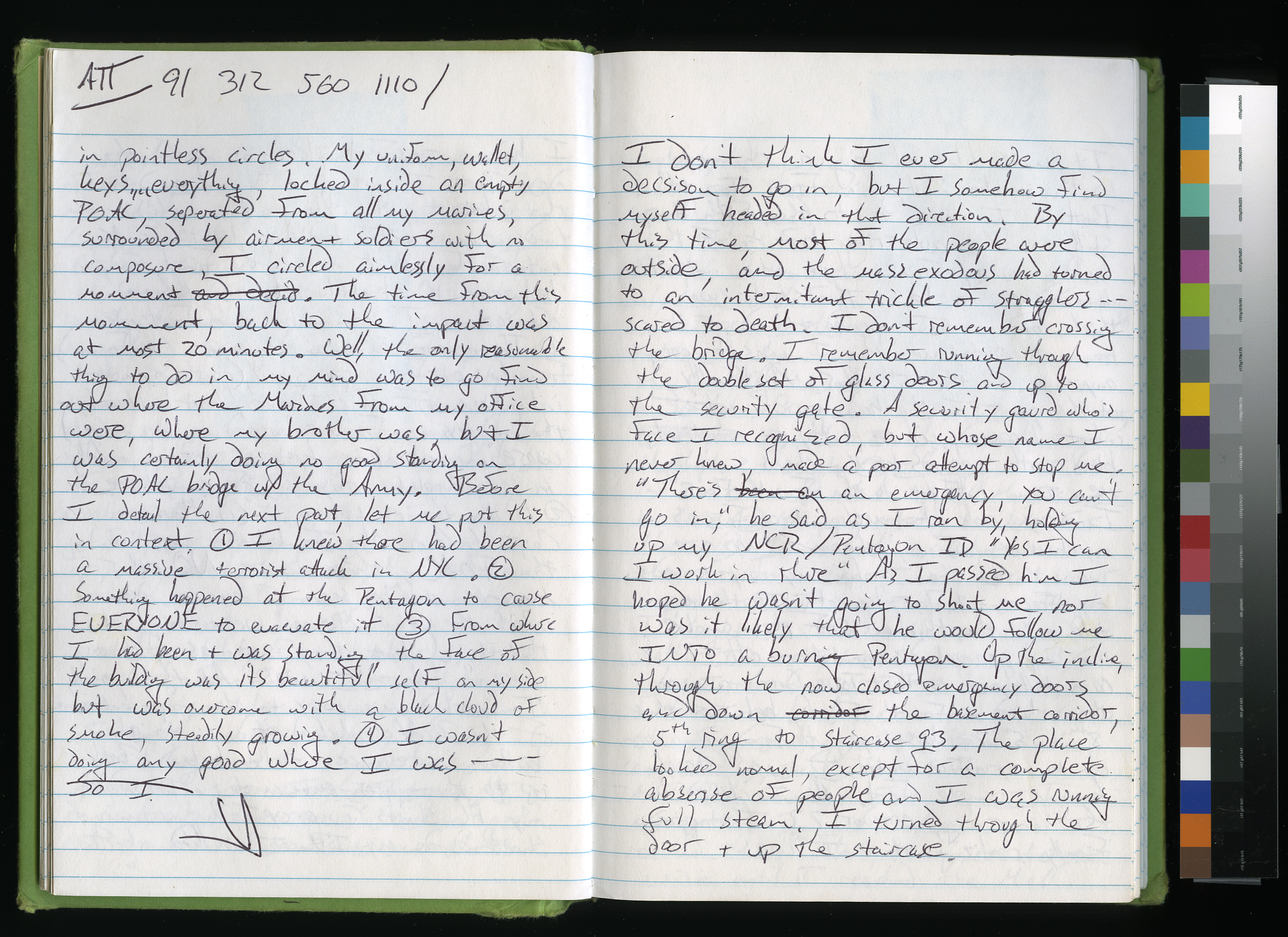

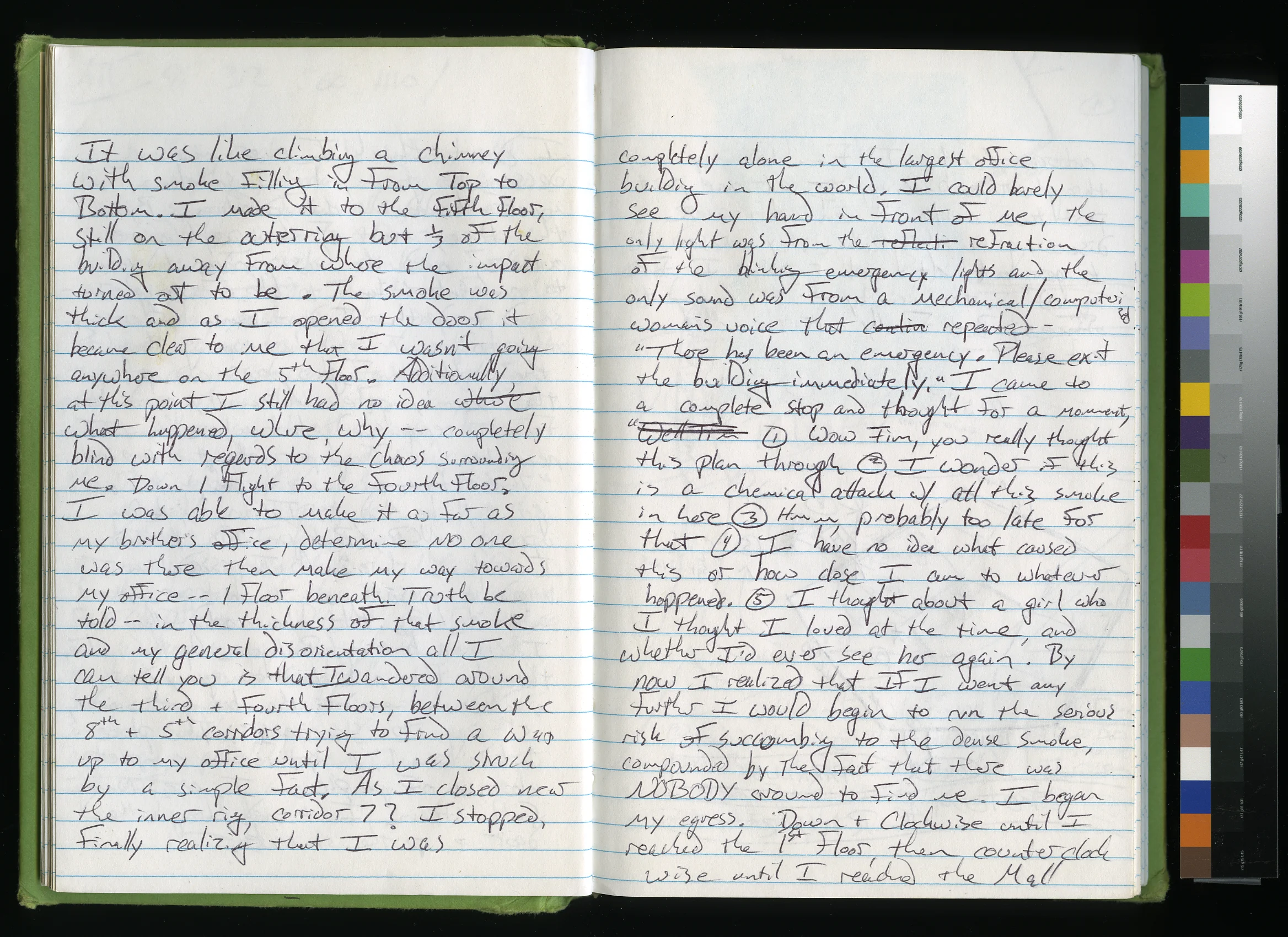

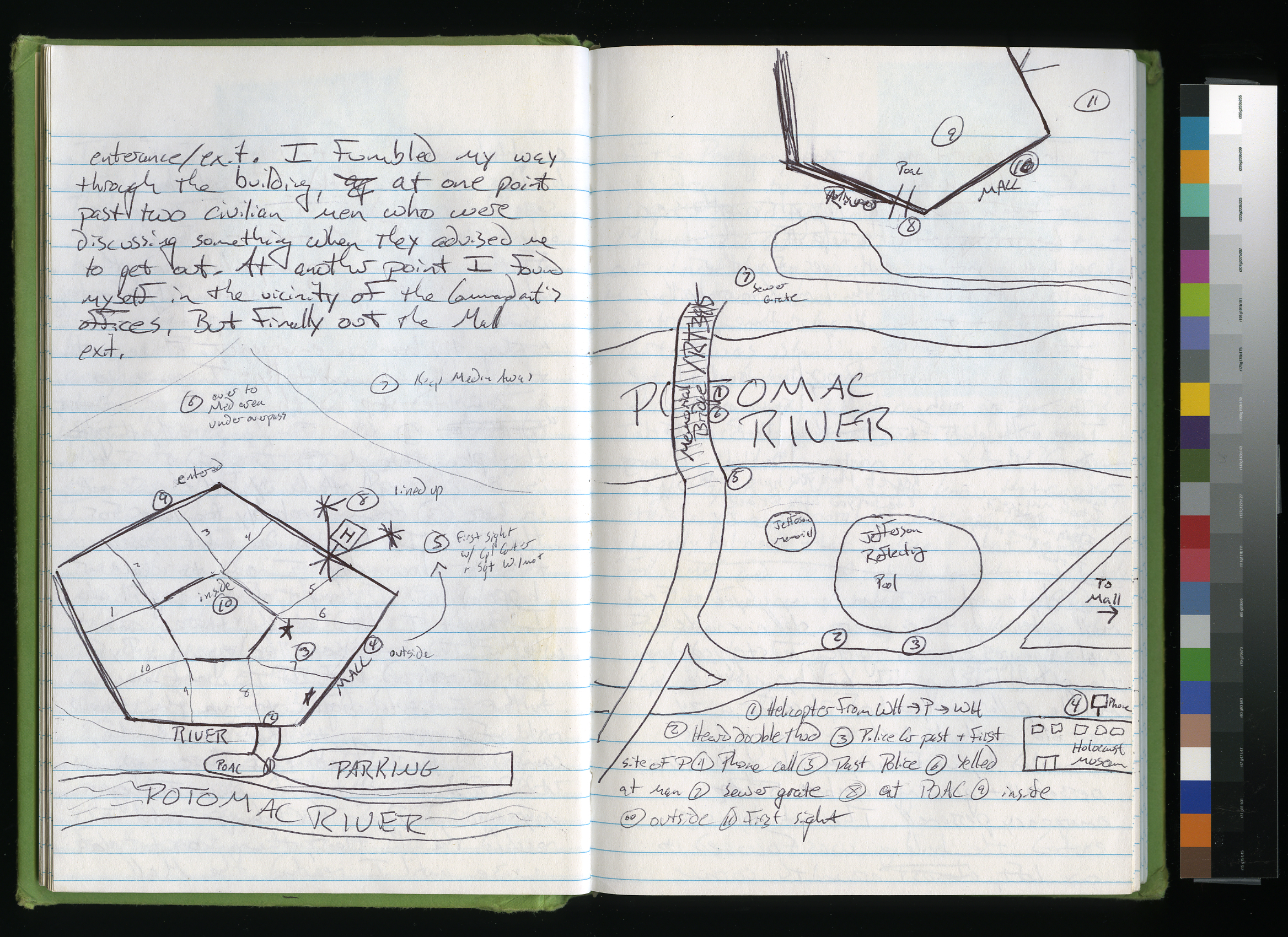

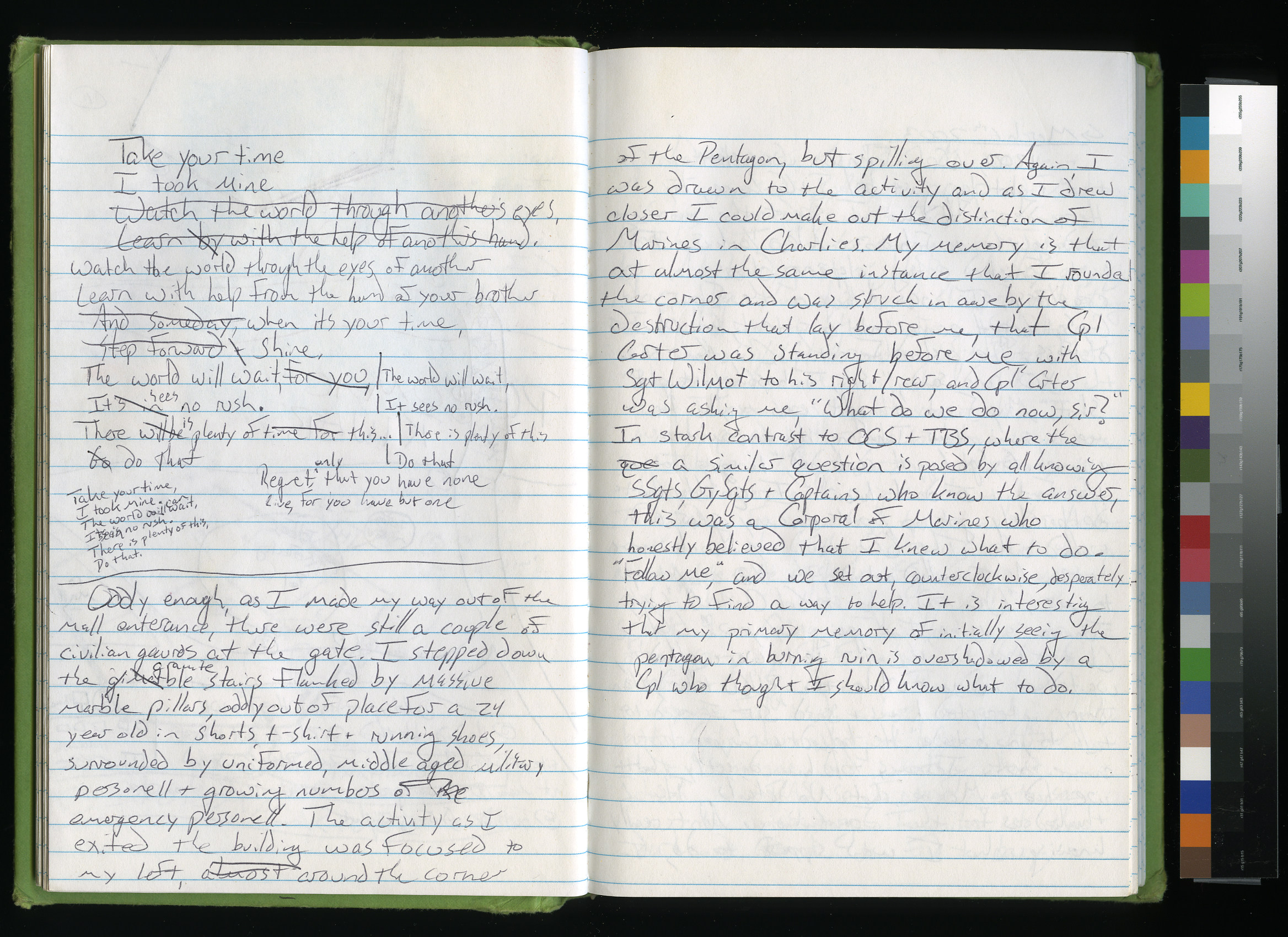

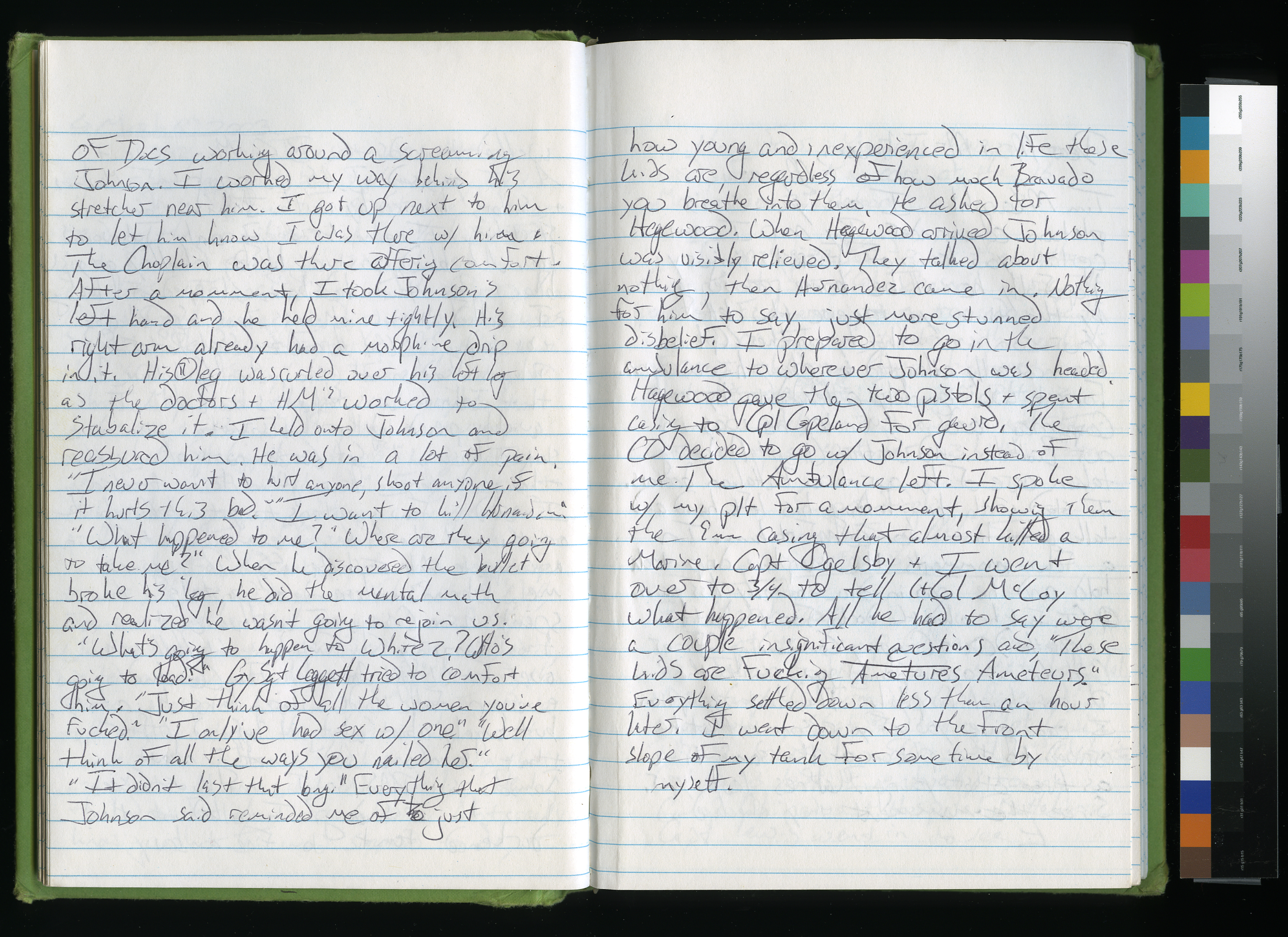

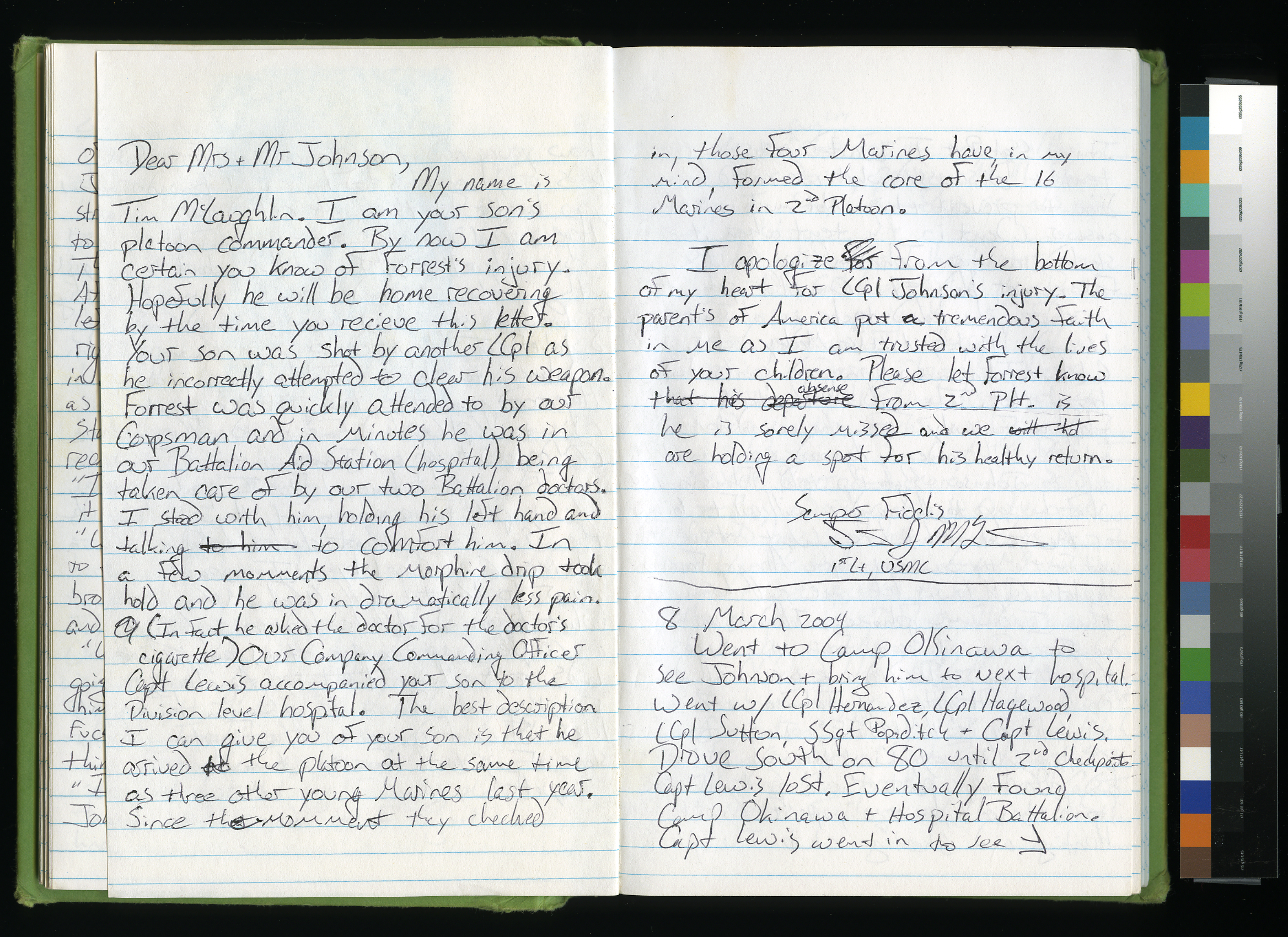

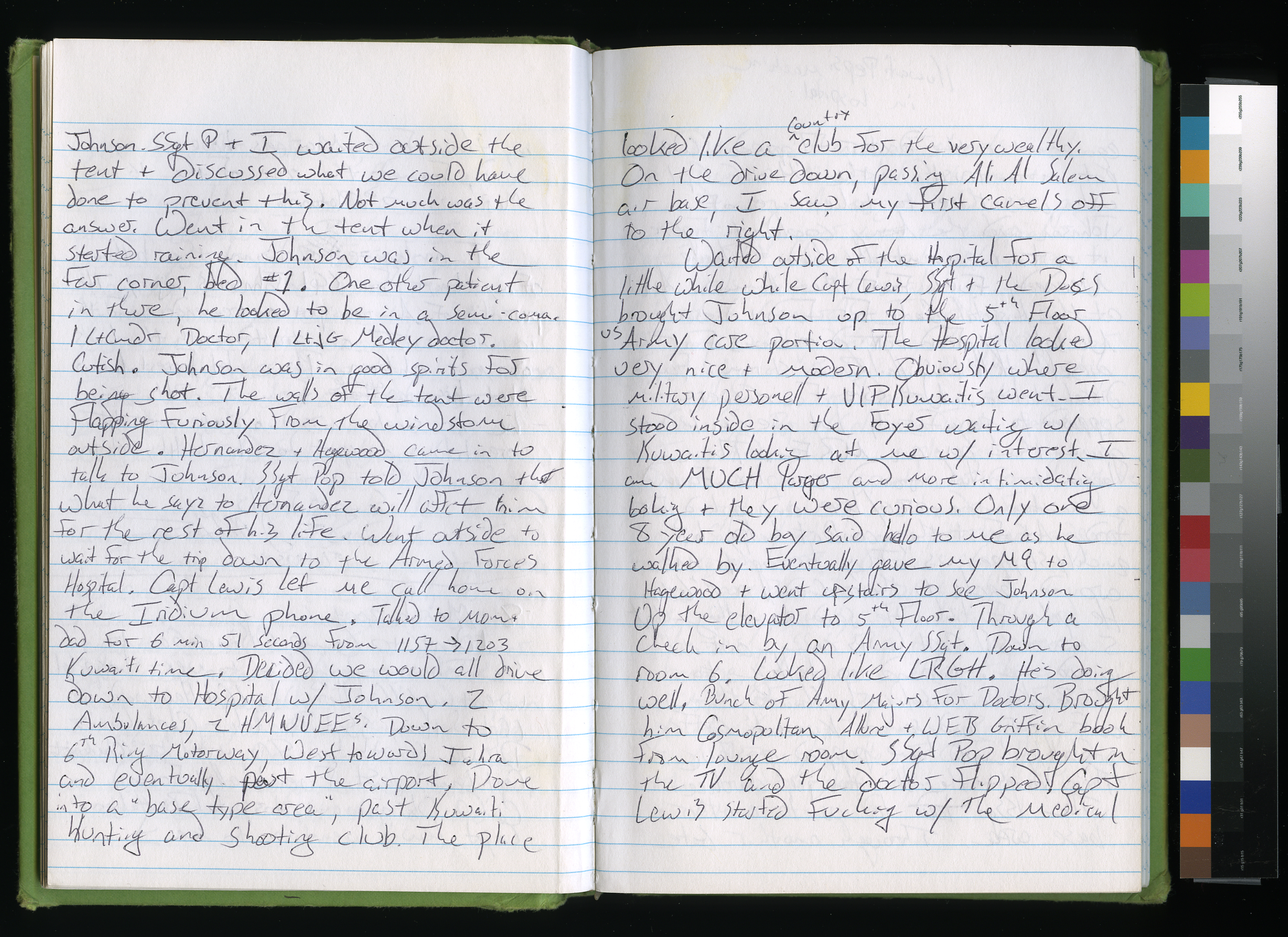

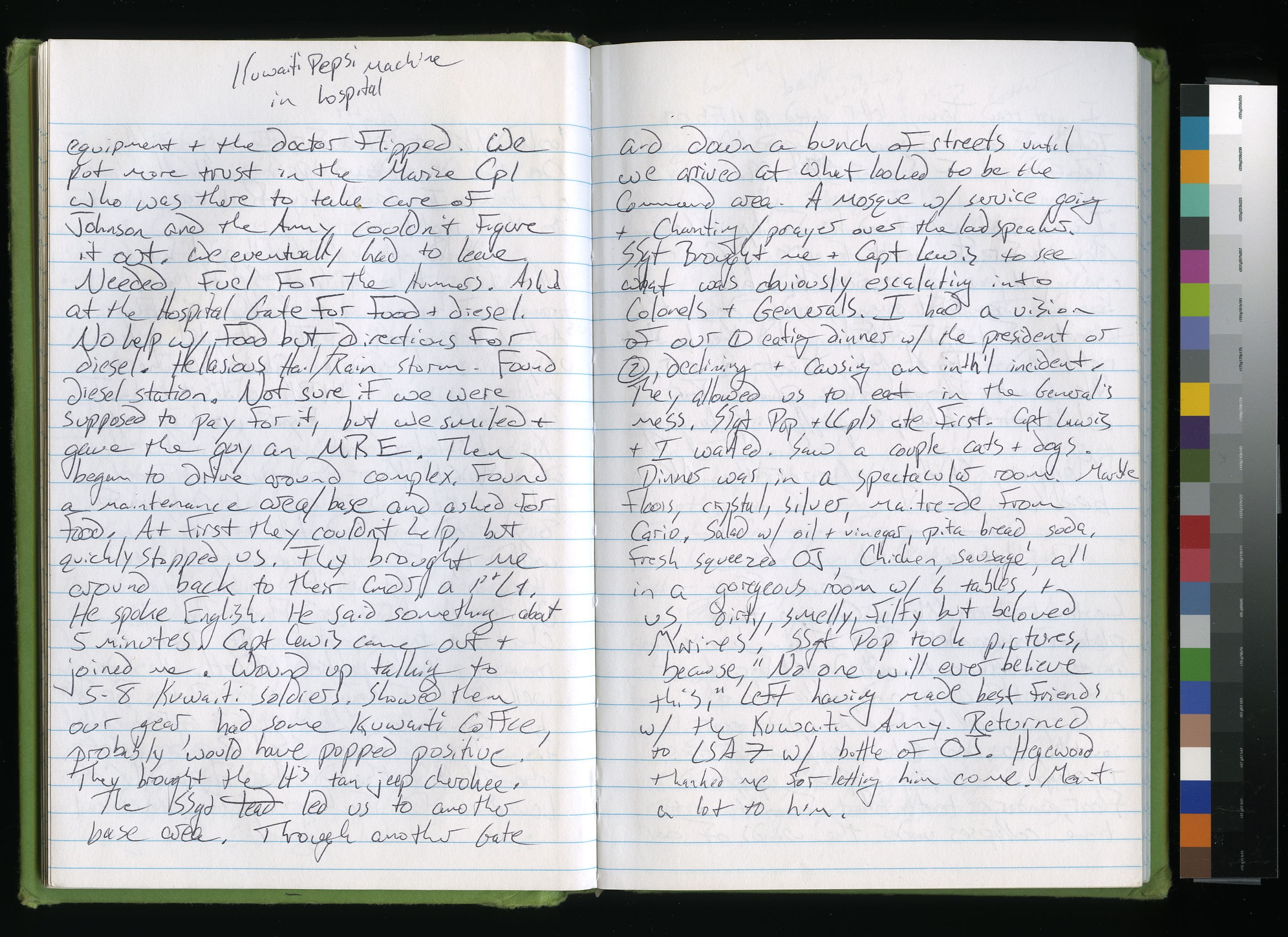

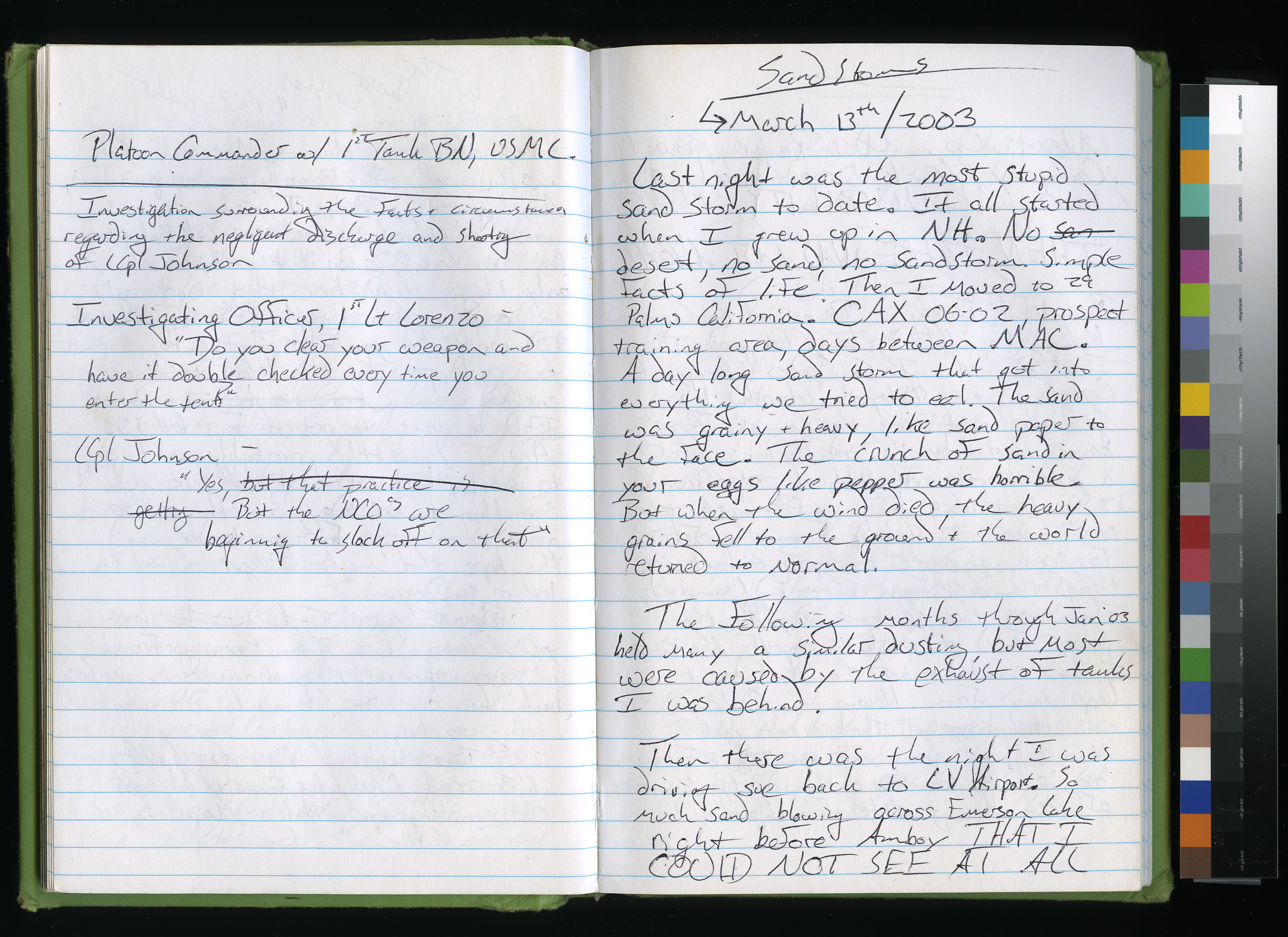

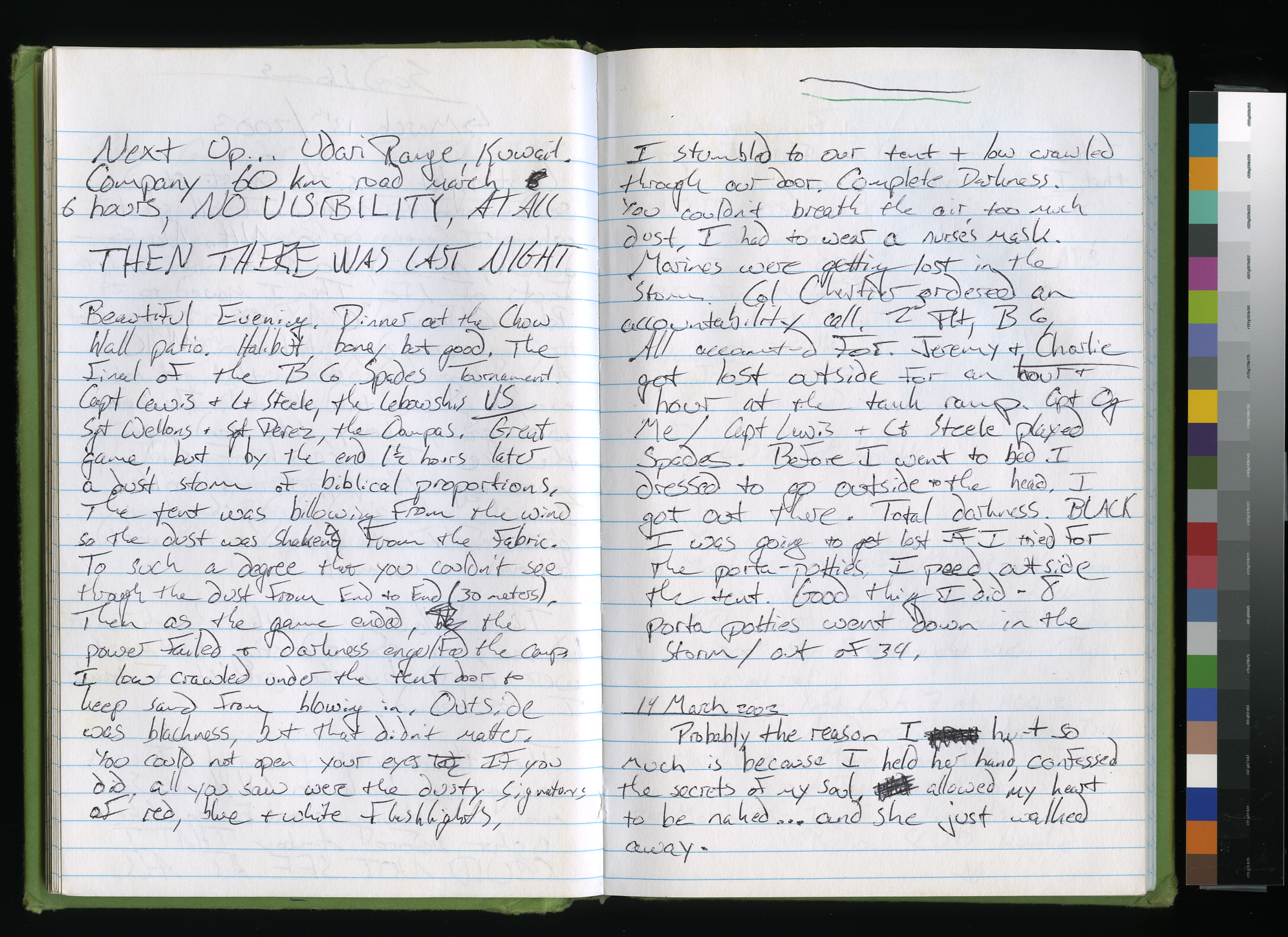

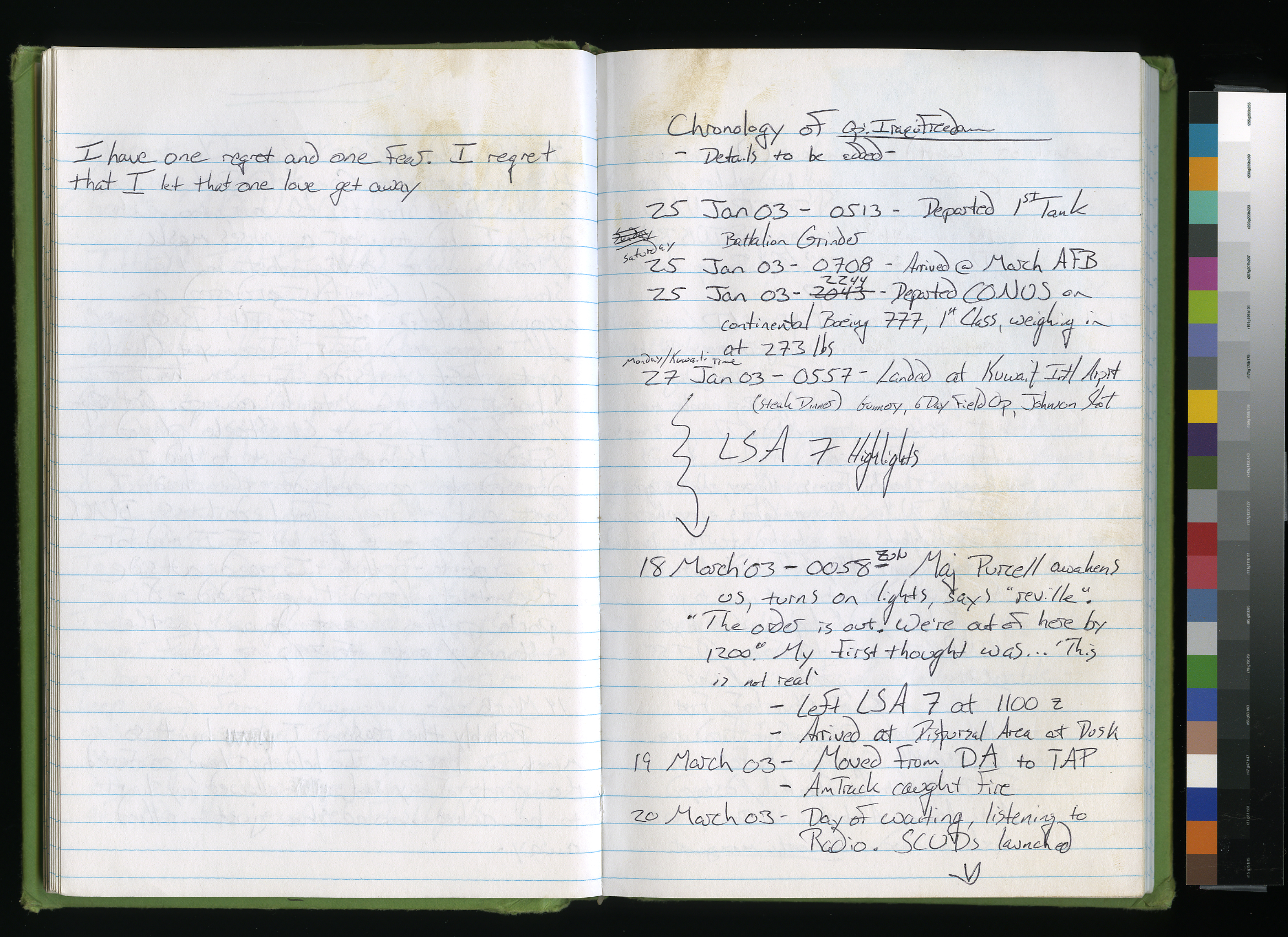

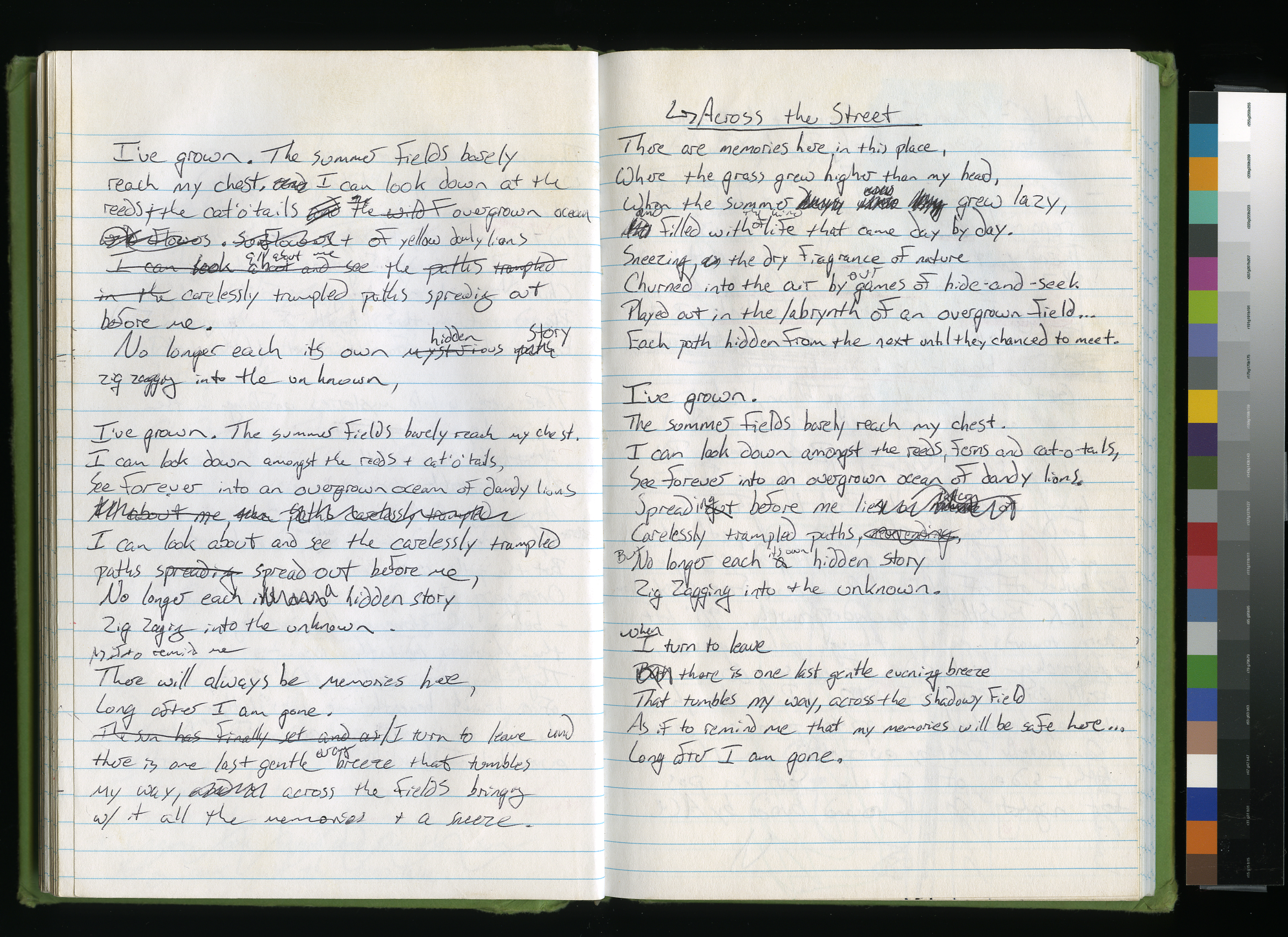

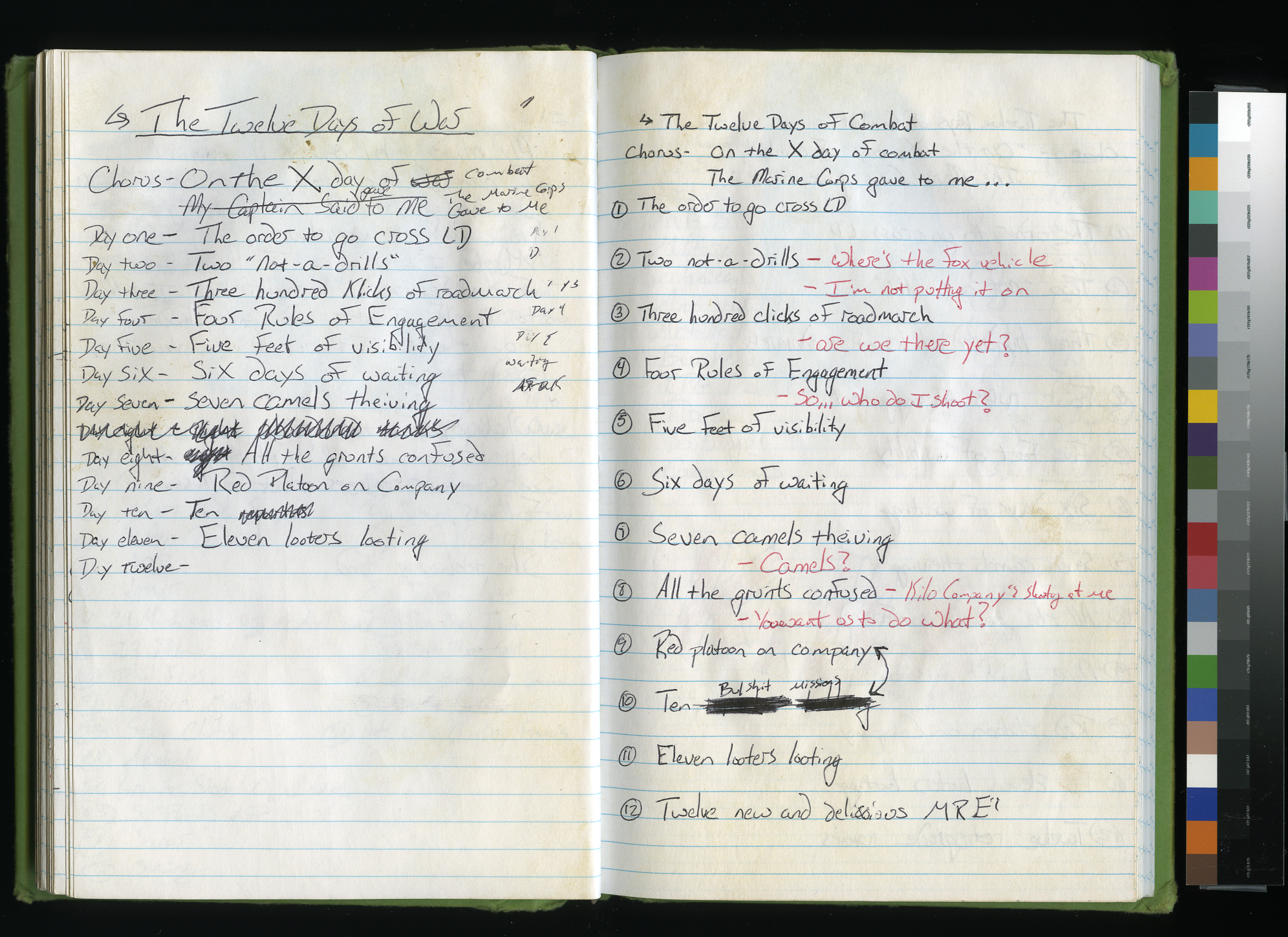

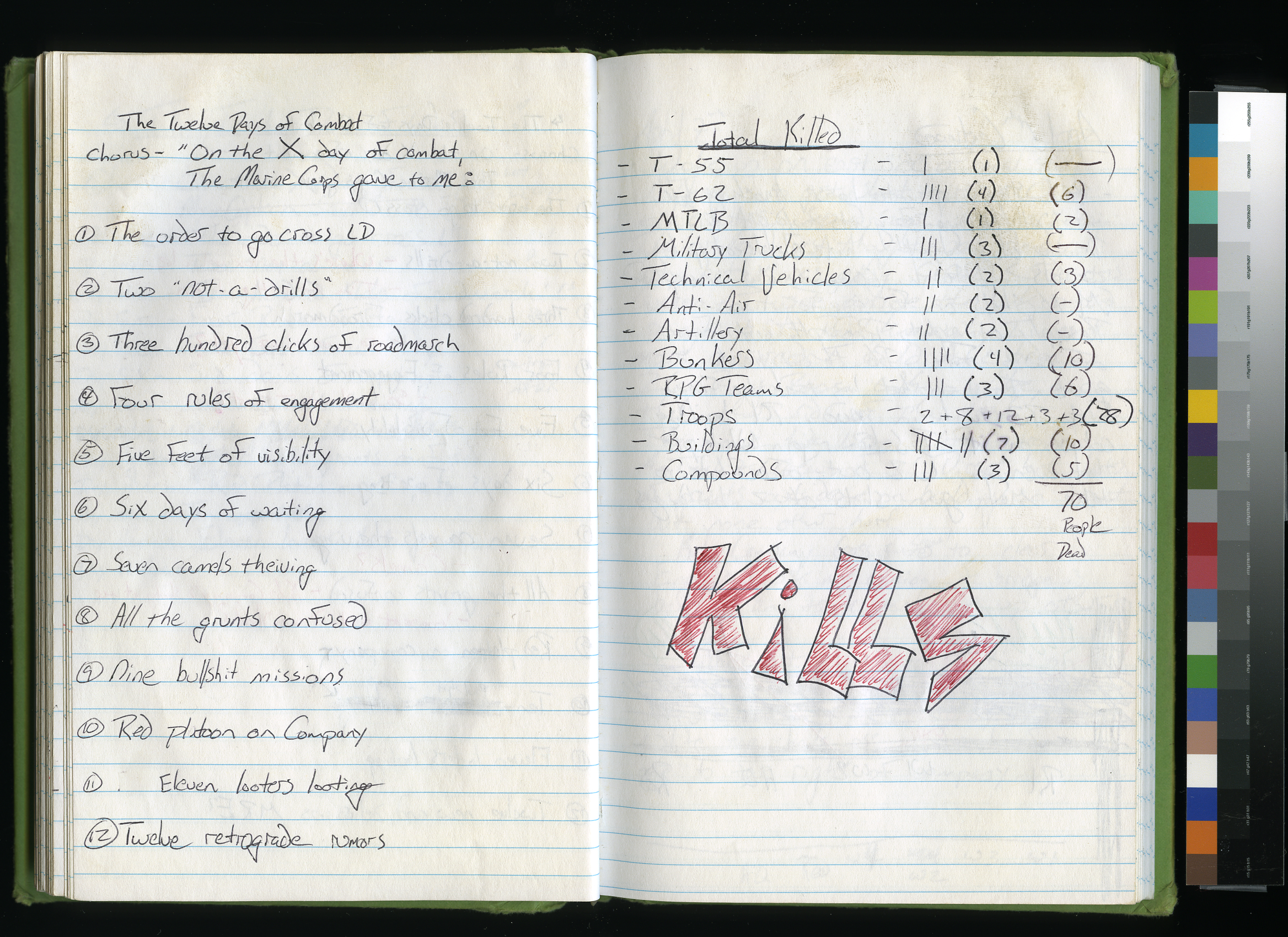

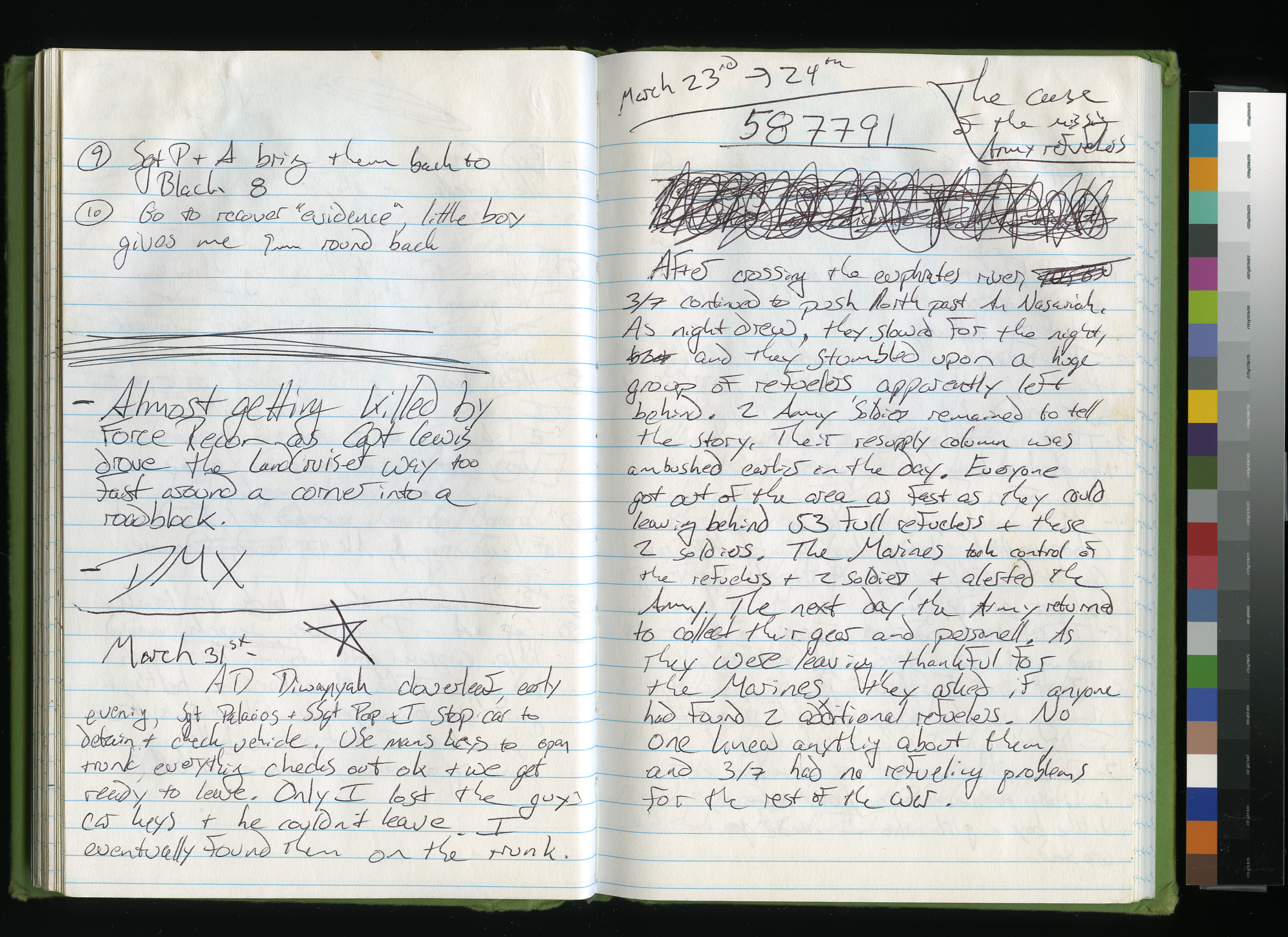

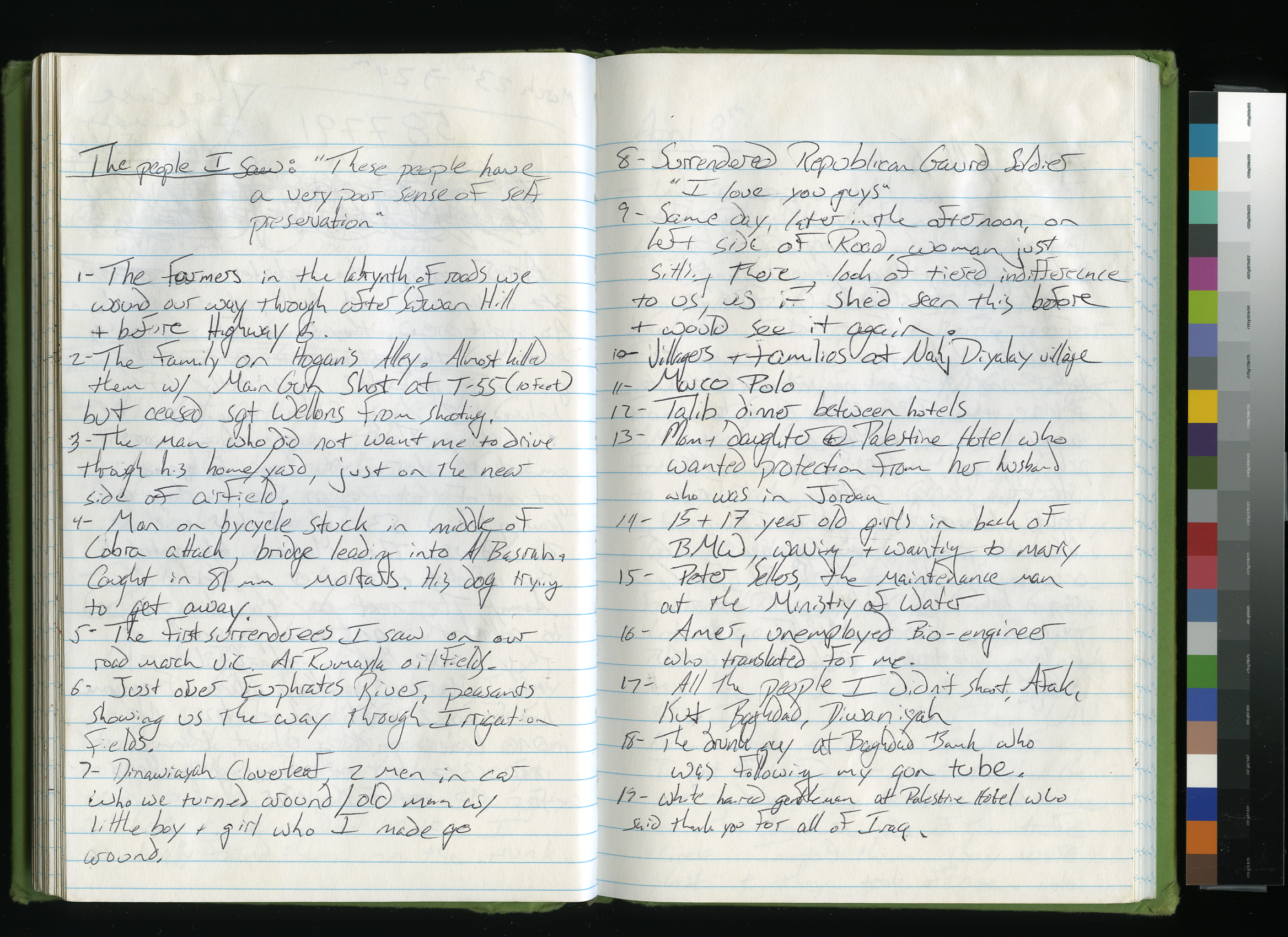

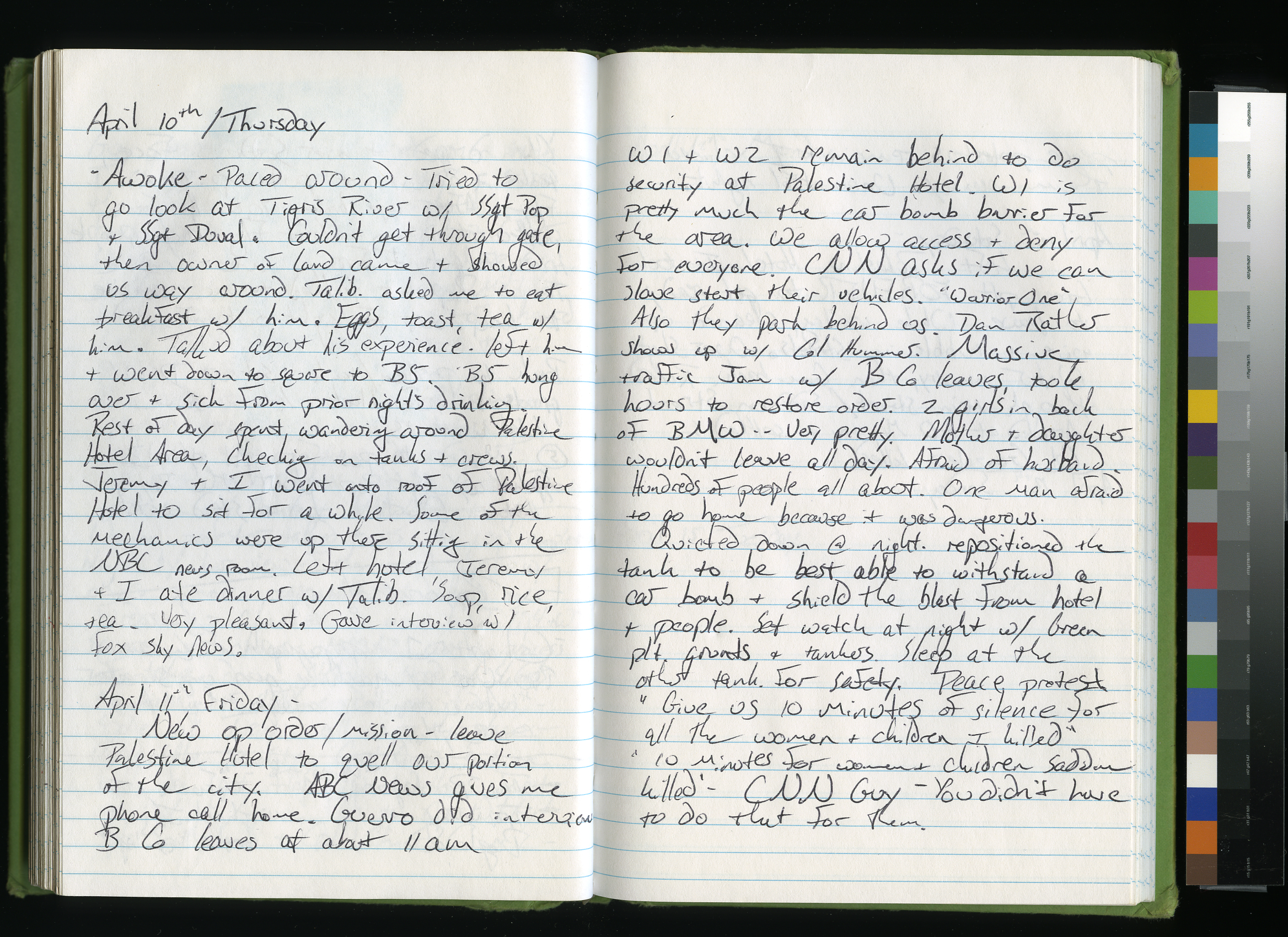

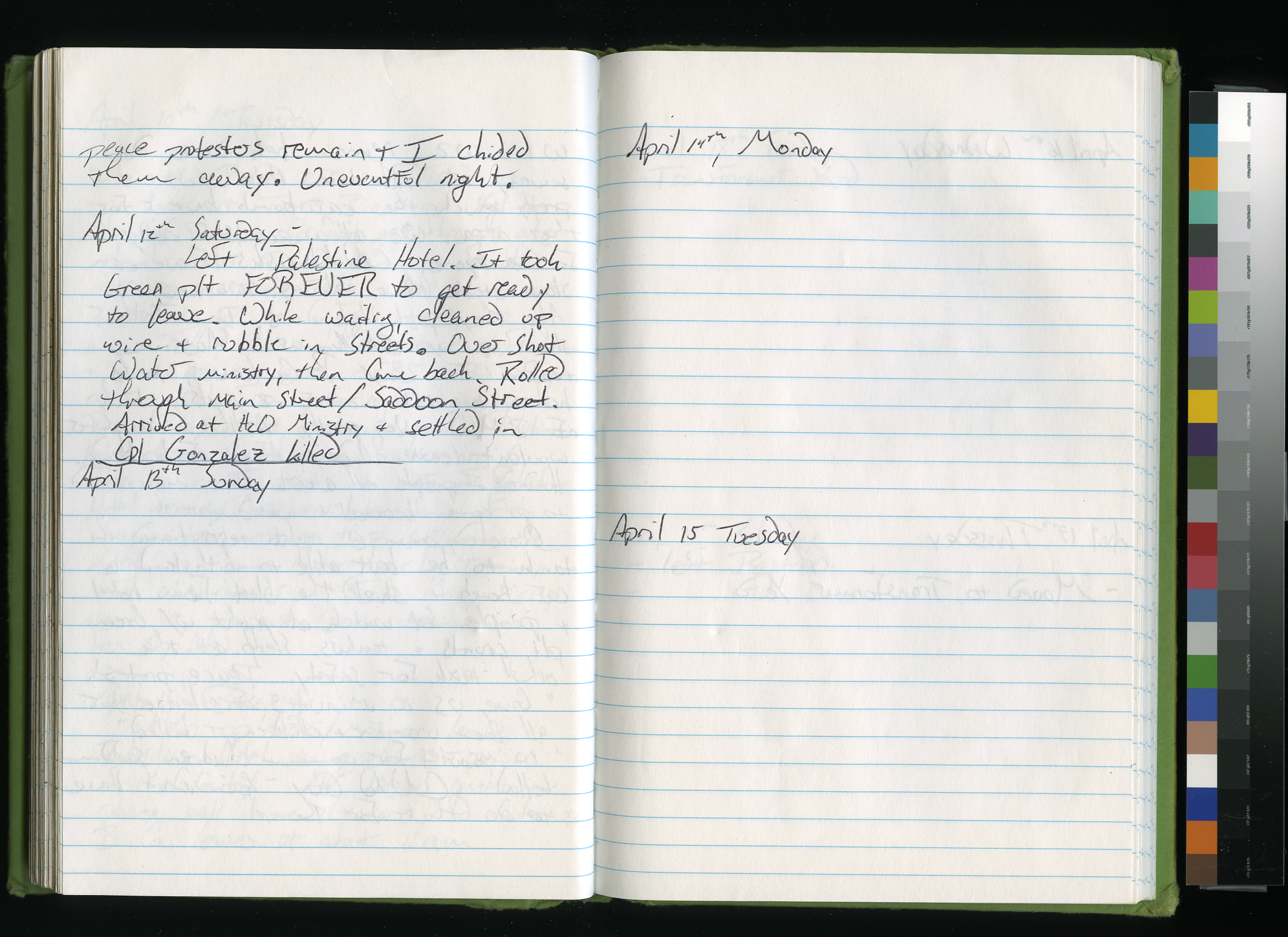

Marine LT Tim McLaughlin's War Journals

Publications

+ Reading List (Includes titles on Afghanistan)

Bedrooms of the Fallen. 2014. Ashley Gilbertson

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot: A Photographer's Chronicle of the Iraq War. 2007. Ashley Gilbertson

WAR. USA.Afghanistan.Iraq. 2004. VII Photo Agency

Disco Night Sept. 11. 2014, Peter van Agtmael

2nd Tour Hope I don't Die. 2009. Peter van Agtmael

Infidel. 2010, Tim Hetherington

War Porn. Christophe Bangert

Unembedded: Four Independent Photojournalists on the War in Iraq. 2005. Kael Alford & Thorne Anderson

Photojournalists on War: The Untold Stories from Iraq. 2013. by Michael Kamber & Dexter Filkins

War is Personal. 2010. Eugene Richards

Iraq: The Space Between. 2007. John Lee Anderson & Christoph Bangert

Testament. 2014. Chris Hondros & Alexandra Ciric

Iraq|Perspectives. 2011. Benjamin Lowy

Silent Exodus: Portraits of Iraqi Refugees in Exile. 2008. Khaled Hosseini & Zalmaï

Rethink: Cause and Consequences of September 11. 2007. VII Photo Agency & Giorgio Baravalle

In the Company of God. 2005. Joao Silva

Afghanistan: The Road to Kabul. 2002 Ron Haviv

The Lion's Grave: Dispatches from Afghanistan. 2003, Jon Lee Anderson

The Fall of Baghdad. 2004, Jon Lee Anderson

The Lovers. 2015. Rod Nordland

Restrepo. 2011. Sebastian Junger

The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq. 2005. George Packer

Night Draws Near: Iraq’s People in the Shadow of America’s War. 20o5. Anthony Shadid

Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. 2006. Thomas Ricks

Imperial Life In The Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone. 2006. Rajiv Chandrasekaran

The Forever War. 2008. Dexter Filkins

The Good Soldiers. 2009. David Finkel

The Yellow Birds. 2012. Kevin Powers

Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. 2012. Ben Fountain

Love My Rifle More than You: Young and Female in the U.S. Army. 2006. Kayla Williams

Plenty of Time When We Get Home: Love and Recovery in the Aftermath of War. 2015. Kayla Williams

The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. 2007. Lawrence Wright

War of the Encyclopaedists: A Novel. 2015. Christopher Robinson & Gavin Kovite

No Man's Land: Preparing for War and Peace in Post--9/11 America. 2015. Elizabeth D. Samet

Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War. 2013. Roy Scranton & Matt Gallagher

Soldier Girls: The Battles of Three Women at Home and at War. 2015. Helen Thorpe

FOBBIT. 2012. by David Abrams

The Corpse Exhibition: And Other Stories of Iraq. 2014. Hassan Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright

Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. 2004. Steve Coll

Thank You for Your Service. 2014. David Finkel

Black Hearts: One Platoon's Descent into Madness in Iraq's Triangle of Death. 2011. Jim Frederick

Kaboom: Embracing the Suck in a Savage Little War. 2011. Matt Gallagher

My Life as a Foreign Country: A Memoir. 2014. Brian Turner

Torture and Truth: America, Abu Ghraib, and the War on Terror. 2004. Mark Danner